Back to search results

MOE COURT HOUSE

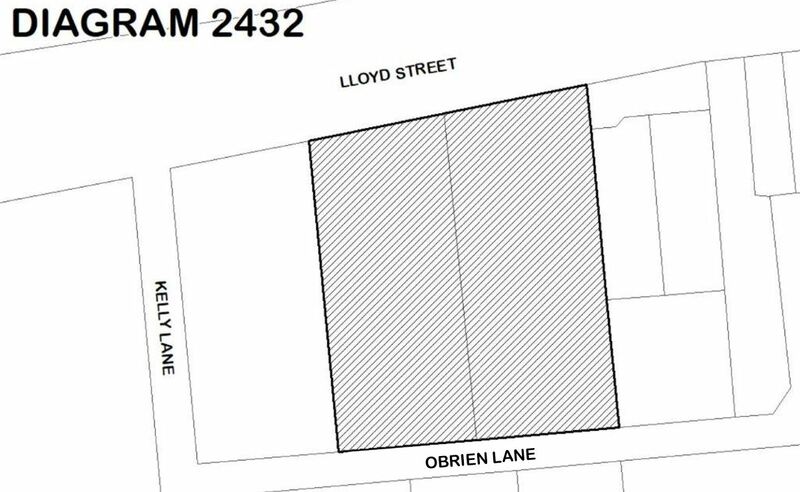

59-61 LLOYD STREET MOE, LATROBE CITY

MOE COURT HOUSE

59-61 LLOYD STREET MOE, LATROBE CITY

All information on this page is maintained by Heritage Victoria.

Click below for their website and contact details.

Victorian Heritage Register

-

Add to tour

You must log in to do that.

-

Share

-

Shortlist place

You must log in to do that.

- Download report

Moe Court Rear of Building Feb 2022

On this page:

Statement of Significance

Moe Court House is located on Gunaikurnai Country.

What is significant?

The Moe Court House, a Brutalist building of brick and off-form concrete construction designed by Public Works Department architect Alan Yorke in 1977 which officially opened in 1979. The building includes significant interior spaces including three court rooms; judge’s rooms with secure private access; a large public waiting room with Telecom Gold Phone; interview rooms; a typing pool and staff amenities space. Significant internal features include steel-pipe roof trusses; slatted ceilings in the courtrooms and foyer; exposed duct work; metal pipe balustrades in stairwells; dark brown quarry tiled floors; built-in furniture including judges’ benches and witness boxes.

How is it significant?

The Moe Court House is of architectural significance to the State of Victoria. It satisfies the following criterion for inclusion in the Victorian Heritage Register:

Criterion D

Importance in demonstrating the principal characteristics of a class of cultural places and objects.

Why is it significant?

The Moe Court House is significant for its importance in demonstrating a large range of the defining characteristics of Brutalist architecture in Victoria. These include its monumental scale and fortress-like character, off-form concrete, jagged roofline, industrial-style glazing and bold sculptural expression of curving elements, angled forms and projecting planes and masses. It also demonstrates less frequently seen characteristics, such as the concrete spouts with rain-chains and a conspicuous external expression of services to a degree uncommonly evident in other similar buildings. Moe Court House is a fine example of a late twentieth-century court house. It was one of the largest court houses to be built in Victoria in the second half of the twentieth century, and likely the largest to have been erected in a regional Victorian centre since the completion of grand complexes at Geelong and Wangaratta in the late 1930s. Comprising three courtrooms, a typing pool and an expansive public waiting area, it demonstrates the centralisation of court administration into large regional hubs from the 1970s.

(Criterion D)

Show more

Show less

-

-

MOE COURT HOUSE - History

Court houses in Victoria

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, many towns and suburbs in Victoria were provided with purpose-built court houses. In regional Victoria this was evident in large towns including Ballarat, Bendigo, Mildura, Warrnambool and Traralgon, as well as smaller towns such as Ararat, Beechworth, Bairnsdale, Buninyong, Daylesford, Gisborne, Hamilton, Kilmore and Stawell. Many remained in use during the twentieth century, and some are still in use to the present day. During the 1920s and 1930s, new courthouses were constructed in a few larger regional towns, most notably the major complexes at Wangaratta (1938) and Geelong (1938) each with three courtrooms. This era also saw several court houses built in Melbourne in architecturally progressive styles, including the Chelsea Court House (1928-29) (VHR H0804) and Camberwell Court House and Police Station (1938-39) (VHR H1194).

From the 1950s, a series of new court houses were constructed in Melbourne and regional Victoria as the population grew after World War II. Eastern Victoria, for example, experienced economic growth due to the expansion of power stations in the Latrobe Valley and the booming timber industry of East Gippsland. New court houses were built in Moe (1955), Morwell (1956) and Orbost (1958). All were modest in scale, built to a standard gable-roofed design developed by the Public Works Department (PWD). New court houses to standard PWD designs were also built at Robinvale (1959), Broadford (1961), Hopetoun (1962), Pakenham (1963), Horsham (1967), Colac (1969) as well as many more in the Melbourne metropolitan area.

By the 1970s there was a crisis in the court system. Legal commentators observed that many courts had ‘old-fashioned facilities’, were ‘grossly overcrowded’ and declared an ‘urgent need for more courts’.[1] The early 1970s saw the construction of larger facilities and a departure from standardised court designs. Notably more individualised architectural designs were pursued. This is evident in the larger two-storey court houses at Preston (1973-74), Prahran (1976-77), Heidelberg (1977-78), Werribee (1977-78), Moe (1977-79) and Broadmeadows (1983-85). Some of the smaller courthouses adopted the Brutalist idiom (Preston, Prahran, and Heidelberg). Of the larger court houses Werribee did not adopt the Brutalist style, but Broadmeadows did, the latter having a typing pool.Court houses in Moe

By 1880 a Police Court and Court of Petty Sessions was in operation at Moe. From 1883 court sittings took place in the new Shire of Narracan Hall. This venue continued to be used as a court into the twentieth century. In 1955 the Borough of Moe separated from the Shire of Narracan, and in 1956 the PWD called tenders for a modest timber-framed court house at Moe. The resulting building served the Shire’s needs until the late 1970s, when a new Moe Court House was proposed.

The new Moe Court House was designed in 1977 by Alan Yorke, Senior Project Architect, PWD. Yorke also designed the Jika Jika High Security Unit at Pentridge Prison which won several awards in 1979 including an Excellence in Concrete award from the Concrete Institute of Australia, and an RAIA Merit Award in the New Buildings category. The contract documentation at Moe was done by Melbourne-based firm Peter Tsitas & Associates Pty Ltd. Migrating from Greece in 1948, Tsitas studied architecture at the University of Melbourne and registered as an architect in 1960. The Moe Court House was constructed between 1978 and 1979 by the Morwell building firm WG Campbell Constructions Pty Ltd supervised by Frank Wu, PWD, a Hong Kong citizen who graduated from the University of Melbourne in 1972. The building was officially opened in November 1979 by the Attorney General of Victoria, the Honourable Haddon Storey, QC.

The Moe Court House was designed as a large regional complex. It had three courtrooms, rather than the usual two, and a spacious public waiting area. On the upper floor a large open-plan typing pool space accommodated 24 typists and there were generous staff amenities areas. The construction of the Moe Court House coincided with advances in computers, fax and photocopying technologies.[2] By 1985 Victoria’s central computerised case management system ‘Courtlink’ revolutionised legal record-keeping by allowing data entry from any court in the state. Courtlink was piloted at the court complexes at Broadmeadows (for metropolitan Victoria) and Moe (for regional Victoria). The typing pool at Moe quickly became the ‘State Typing Pool’ for the whole of the magistrates’ court system Victoria, where data from hard copy documents was typed into Courtlink.[3] The location of the court and typing pool at Moe provided much needed jobs in Gippsland as the coal mining economy was waning. The typing pool was predominantly staffed by women some working until the court’s closure in 2014.The Brutalist style

The Moe Court House was designed in the Brutalist architectural style. Typically, Brutalist buildings were assertive, and featured powerful, blocky forms and were honest in their use of materials and form of construction. Brutalist architecture first appeared in Australia in the 1960s. It was a robust and highly adaptable style suited to institutional buildings, and the first examples appeared at university campuses. In Victoria, influential architects Kevin Borland, Graeme Gunn, Evan Walker and Daryl Jackson adopted the style from the late 1960s for major commissions. Borland and Jackson produced the notable Brutalist design for the Harold Holt Memorial Swimming Centre (VHR H0069) constructed in 1969. During the early 1970s, Brutalism became the style of choice for the union movement as evidenced by the Plumbers and Gasfitters Union Building (VHR H2307) and Clyde Cameron College (VHR H2192). Brutalism was also influential within the PWD. Although the popularity of Brutalism diminished through the 1980s, it is now considered a key architectural style of the twentieth century. Brutalist buildings have received some criticism for lacking warmth and humanity, which contributed to the more playful approaches in postmodernist architectural approaches.

Critical Reception

The Moe Court House generated discussion in architectural circles. In December 1979, it was the subject of a four-page article in the journal of the RAIA (Victorian chapter). In 1980, the building was reviewed by the Age newspaper’s architecture critic Norman Day, who referred it as ‘playful and amusing architecture for a stern legal function’. He wrote that ‘architect Yorke has given us much more than we ordinarily expect from the Government Architect’s office. His design is gutsy and aggressive…’ (Age, 22 January 1980, p.2). In 1980 the building was shortlisted for a Victorian Institute of Architects Award in the New Buildings category. The Moe Court House remained in operation for over three decades until 2014 when its functions moved to Morwell, where a new judicial complex was erected in 2007. The Moe Court House is currently unoccupied (2022).

Selected bibliographyGovernment publications“Orders in council (Series 1976-77)”, Victoria Government Gazette, No 44, 8 June 1977, p.1556.

“Contracts accepted (Series 1977-78)”, Victoria Government Gazette, No 10, 8 February 1978, p.322.

Explanatory Memorandum, Public Works & Services Bill 1977 (Victoria), pp.6-7.

Explanatory Memorandum, Public Works & Services Bill 1978 (Victoria), p.8.

Explanatory Memorandum, Public Works & Services Bill 1979 (Victoria), p.8.

Victorian Parliamentary Debates, Legislative Assembly, 11 March 1980, pp.6767-68.

Newspaper and magazine articles“Awards 80”, Architect, December 1980, p.11.

Mark Baker, ‘Chaos in the Court’, Age, 25 March 1975, p.7.

Norman Day, “Pop courthouse lacks snap”, Age, 22 January 1980, p.2.

Rod Duncan, ‘Vale Peter Tsitas, MPIA’, Planning News, Vol 47, No 2 (March 2021), p.19.

Richard Eckhaus, “Soggy plate of cereal”, Age, 30 January 1980, p.10.

Nancy Patton, ‘Moe Magistrates Court and Typing Pool’, Architect, December 1979, pp.20-23.

Peter Sorel, “Propriety of criticism”, Age, 30 January 1980, p.10.

Gary Tippett, “Stark surroundings for a grim, sad tale”, Age, 25 March 1998, p.2.

Books, book chapters, papers and thesesArie Frieberg, Stuart Ross and David Tait, ‘Change and Stability in Sentencing: A Victorian Study’, The University of Melbourne 1996.

Phaidon Editors, Atlas of Brutalist Architecture, Phaidon Press Ltd, 2020

Philip Goad, Judging Architecture. Issues, Divisions, Triumphs: Victorian Architecture Awards, 1929-2002, Melbourne: RAIA Victoria, 2003, p.293.

Philip Goad & Hannah Lewi, Australian Modern, Hawthorn: Thames & Hudson Pty Ltd, 2019, p.28.

Elizabeth Wade, 'Clerks of Courts: Power and Change in the Victorian Magistrates’ Courts, 1948 - 1989', PhD thesis, Victoria University, 2021.

Heritage Citations, Assessments and ReportsContext Pty Ltd, Latrobe City Heritage Study: Volume 3, Heritage Place & Precinct Citations, 2008.

Heritage Alliance, Survey of Post-War Built Heritage in Victoria: Stage One, 2008.

[1] Mark Baker, ‘Chaos in the Court’, Age, 25 March 1975, p.7.

[2] Elizabeth Wade, 'Clerks of Courts: Power and Change in the Victorian Magistrates’ Courts, 1948 - 1989', PhD thesis, Victoria University, 2021, p. 118-119.

[3] Arie Frieberg, Stuart Ross and David Tait, ‘Change and Stability in Sentencing: A Victorian Study’, The University of Melbourne 1996, Appendix 2.1, p. 1.MOE COURT HOUSE - Assessment Against Criteria

The Moe Court House is of architectural significance to the State of Victoria. It satisfies the following criterion for inclusion in the Victorian Heritage Register:

Criterion DImportance in demonstrating the principal characteristics of a class of cultural places and objects.

MOE COURT HOUSE - Permit Exemptions

General Exemptions:General exemptions apply to all places and objects included in the Victorian Heritage Register (VHR). General exemptions have been designed to allow everyday activities, maintenance and changes to your property, which don’t harm its cultural heritage significance, to proceed without the need to obtain approvals under the Heritage Act 2017.Places of worship: In some circumstances, you can alter a place of worship to accommodate religious practices without a permit, but you must notify the Executive Director of Heritage Victoria before you start the works or activities at least 20 business days before the works or activities are to commence.Subdivision/consolidation: Permit exemptions exist for some subdivisions and consolidations. If the subdivision or consolidation is in accordance with a planning permit granted under Part 4 of the Planning and Environment Act 1987 and the application for the planning permit was referred to the Executive Director of Heritage Victoria as a determining referral authority, a permit is not required.Specific exemptions may also apply to your registered place or object. If applicable, these are listed below. Specific exemptions are tailored to the conservation and management needs of an individual registered place or object and set out works and activities that are exempt from the requirements of a permit. Specific exemptions prevail if they conflict with general exemptions. Find out more about heritage permit exemptions here.Specific Exemptions:The following works and activities are not considered to cause harm to the cultural heritage significance of the Moe Court House.

General• Minor repairs and maintenance which replaces like with like. Repairs and maintenance must maximise

protection and retention of significant fabric and include the conservation of existing details or elements. Any

repairs and maintenance must not exacerbate the decay of fabric due to chemical incompatibility of new

materials, obscure fabric or limit access to such fabric for future maintenance.

• Maintenance, repair and replacement of existing services such as plumbing, electrical cabling, surveillance

systems, solar power infrastructure, pipes or fire services which does not involve changes in location or scale,

or additional trenching. While this exemption is deemed to include general roof plumbing such as metal downpipes and guttering, it does not include the rain chains that link concrete spouts to the ground level.

• Repair to, or removal of, items such as antennae; aerials; bird spikes; and air conditioners and associated pipe work, ducting and wiring (except where ductwork has been expressed as an architectural feature).

• Works or activities, including emergency stabilisation, necessary to secure safety in an emergency where a

structure or part of a structure has been irreparably damaged or destabilised and poses a safety risk to its

users or the public. The Executive Director must be notified within seven days of the commencement of these

works or activities.

• Painting of previously painted external and internal surfaces in the same colour, finish and product type

provided that preparation or painting does not remove all evidence of earlier paint finishes or schemes. This

exemption does not apply to areas which are currently unpainted.

• Removal of graffiti from window glazing and previously painted external surfaces.

• Removal of non-original signage including lettering on windows and glazed doors, self-adhesive stickers, “parking-related signage (on external walls, columns and lampposts), fire service signage (including fire exits, fire exit evacuation diagrams and fire extinguisher/fire hydrant signs) and printed paper signs. This exemption does not apply to the original external signage on the front of the building, stating MOE COURTHOUSE.

• All usual domestic cleaning, plus cleaning to maintain exterior including the removal of surface deposits using

low-pressure water, neutral detergents and brushing and scrubbing with plastic (not wire) brushes.

· Maintenance and repairs to roof to prevent water ingress. This includes localised replacement of roofing material where the external appearance from ground level remains the same.

Interiors• Works to maintain or upgrade existing toilet facilities (for public, staff and judges) and staff kitchenette including installing new appliances, joinery, re-tiling and the like. This exemption does not include apply to the kitchen in the staff room at the first floor level.

• Removal of non-original stud partition walls at the typing pool level.

• Like for like replacement of carpets.

• Like for like replacement of panels in suspended ceilings.

• Like for like replacement of plastic diffusers to recessed fluorescent lighting trays.

• Removal, replacement or installation of new hooks, brackets and the like for mounting signage or artworks (except for those interior walls with original face brick or off-form concrete finish).

• Maintenance, repair and like for like replacement of existing light fixtures in existing locations.

• Installation, removal or replacement of existing electrical wiring, providing it is concealed.

• Removal of plastic wall-mounted conduits for electrical wiring

• Removal or replacement of light switches or power outlets.

• Removal of ceiling-mounted television sets and other non-original audio-visual equipment from courtrooms.

• Removal of wall-mounted display boards, whiteboards, pin-boards and the like.

• Removal or replacement of smoke/fire detectors, alarms and the like, of same size and in existing locations.

• Repair, removal or replacement of existing ventilation, cooling and heating systems provided that the plant is

concealed, and that the work is done in a manner which does not alter building fabric. This exemption does not apply to air-conditioning ducts that have been deliberately exposed and expressed as an architectural feature.

• Installation, removal or replacement of insulation in the roof space.

Landscape/outdoor areasHard landscaping and services• Subsurface works to watering, utilities and drainage systems provided existing lawns, gardens and hard landscaping, including paving, are to be returned to the original configuration and appearance on completion of works.

• Like for like repair and maintenance of existing hard landscaping including paving and garden bed edging where the materials, scale, form and design is unchanged.

• Like for like repair and maintenance of car parking areas (asphalt or concrete surfacing, concrete kerbing, etc) where the materials, scale, form and design is unchanged.

• Like for like repair and maintenance of freestanding lampposts at front and rear of building, including like for like replacement of spherical white glass luminaires.

• Installation of physical barriers or traps to enable vegetation protection and management of vermin such as

rats, mice and possums.

• Removal, replacement or relocation of non-original freestanding rubbish bin in forecourt.

Gardening, trees and plants• The processes of gardening including mowing, pruning, mulching, fertilising, removal of dead or diseased

plants (excluding trees), replanting of existing garden beds, disease and weed control and maintenance to care

for plants.

• Removal of tree seedlings and suckers without the use of herbicides.

• Management and maintenance of trees including formative and remedial pruning, removal of deadwood and

pest and disease control.

• Emergency tree works where it is necessary to maintain safety or protect property.

• Removal of environmental and noxious weeds.

-

-

-

-

-

Bofors Anti-Aircraft Gun

Vic. War Heritage Inventory

Vic. War Heritage Inventory -

Moe War Memorial

Vic. War Heritage Inventory

Vic. War Heritage Inventory -

Moe RSL Club Memorial Plaques

Vic. War Heritage Inventory

Vic. War Heritage Inventory

-

194 Albion Street, Brunswick

Merri-bek City

Merri-bek City -

194A Albion Street, Brunswick

Merri-bek City

Merri-bek City

-

-