BABY HEALTH CARE CENTRE

ELM GROVE COBURG, MERRI-BEK CITY

-

Add to tour

You must log in to do that.

-

Share

-

Shortlist place

You must log in to do that.

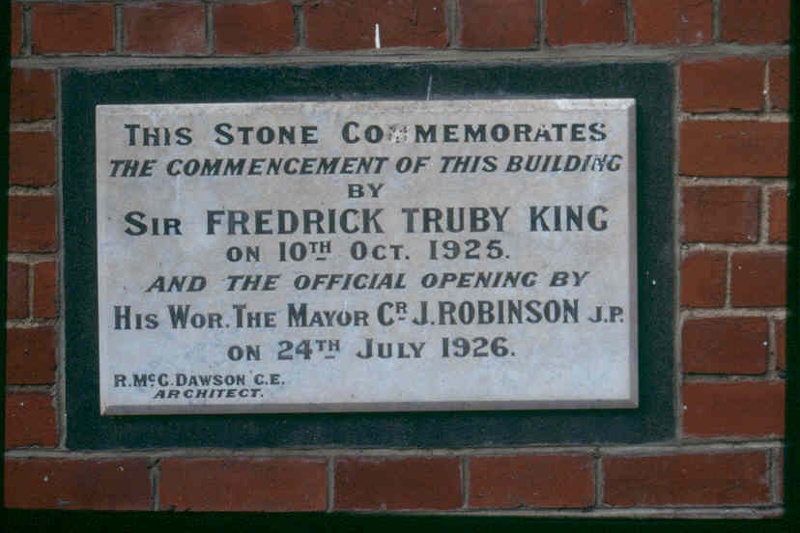

- Download report

Statement of Significance

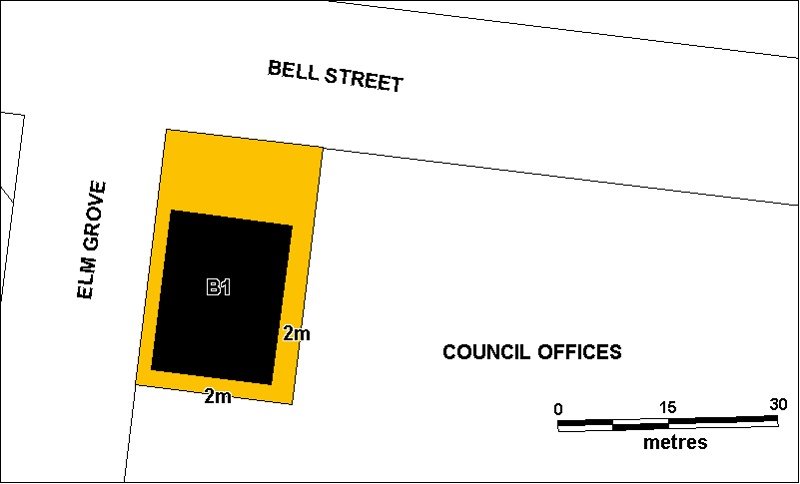

The Coburg Truby King Baby Health Centre was opened by Mayor Cr J Robinson on 24 July 1926. It succeeded an earlier centre opened on 4 December 1919, the first Truby King Centre to open in Victoria. A growing population and an increasing awareness of the service offered by the centre led to overcrowding and the need for new quarters. In 1925 architect, R McC Dawson designed a new building, and in October that year Dr Sir Truby King laid the foundation stone. The new purpose-built centre opened nine months later. The building facilities were, and continue to be, shared with the Coburg City Band. Located in the Coburg civic precinct, the centre has the domestic appearance and scale of a Californian bungalow house. Constructed of red brick with terra cotta tile roof, it has two projecting entrance porches, each gabled, supported by grouped timber posts and solid brick piers. A rendered parapet between the porches has raised lettering indicating "Coburg City Band and Truby King Rooms 1926". Dr Sir Frederick Truby King of New Zealand began promoting his world-famous methods in mothercraft around the turn of the century, and in about 1913 Sister M.V. Primrose of South Yarra inaugurated the movement in Victoria in conjunction with the Trained Nurses' Association.

How is it significant?

The Coburg Truby King Baby Health Centre is of historical and social significance to the State of Victoria.

Why is it significant?

The building of 1926 is historically important as the first purpose-built Truby King Baby Health Centre to be erected in Victoria. The centre has further historical importance for its links to the earlier Coburg baby health centre, which was the first such centre in Victoria to practice Truby King mothercraft methods when it opened in 1919.

The centre has further historical importance for its association with Dr Sir Frederick Truby King of New Zealand, who became famous worldwide for his promotion of the "Plunket Nursing system" which advocated a complicated feeding formula and a strict routine for babies. His methods were largely ignored by the Victorian Baby Health Care Association who chose to promote other expert opinions. King laid the foundation stone for this centre in 1925, and opened the Victoria's first centre in Coburg in 1919.

The building is socially important for its enduring civic value to the community. Its function which combines facilities for baby health as well as for the city's brass band meetings has been an unlikely but successful union since the building's opening, with the premises being in continual use since then. As a baby health centre, the building is socially and culturally important for marking phases in the lives of mothers and infants. Designed to resemble a typical middleclass suburban house, the purpose-built centre was a symbol of domesticity. It was also symbolic of a culturally progressive caring society, a place associated with new scientific ideas, and professionally designed programs designed to improve the health education of women raising families in the developing suburbs.

-

-

BABY HEALTH CARE CENTRE - History

This history was written by Michele Summerton. It draws largely on Cheryl D. Crockett, ‘The History of the Baby Health Centre Movement in Victoria 1917 - 1976, Including a Heritage Study of Extant Purpose-built Baby Health Centre Buildings Constructed Before 1950’, Department of History, Monash University, 31 January 1997.

The health of mothers and babies became a topic for concern in Australia in the first decades of this century. There were concerns about the birthing process and the sicknesses, permanent disabilities and even deaths experienced. The authorities were slow to address these worries, and the dissemination of safer birthing control methods was also officially discouraged. During these years newly formed womens groups were involved in these issues, but even by 1928, years after these issues were first raised, a Royal Commission on Health reported that maternal mortality and disability still constituted ‘a grave national danger’(Crockett 1997:1: Royal Commission on Health, Report, Commonwealth Parliamentary Papers 1926-28 vol 4, p 32).An attempt to combat infant mortality had been made in 1909 with the formation of the Lady Talbot Milk Institute. Its main activity was to oversee the distribution of regulated fresh milk supplies, as there were increasing doubts about the quality of cow’s milk (as a very perishable commodity) and its suitability for infants, a concern that was already being addressed in NSW and overseas. The Institute relied on state and municipal grants, and Talbot nurses visited houses imparting knowledge to women on how to nurse their children and store milk. Small ice chests and blocks of ice were also sent as part of the service (Crockett:2)

By 1916 it was becoming clear that the best food for babies is human milk. That year a report by a committee of Melbourne medical practitioners advised that every effort should be made to educate mothers about maintaining their health and to encourage them to breast feed their babies. They advised that any cow’s milk should be pure and the supply should be controlled and adequately provided. They noted that mortality rates amongst infants had largely been due to infected milk, and they deplored the conditions under which most milk was still handled between the numerous stages between farm and home. In order to improve education on the ‘feeding, nursing and care of infants’, the committee recommended the establishment of ante-natal and infant clinics similar to those in England (Crockett:2: VPRS 9291P1/17/T/6, p 34). They strongly advised on implementing a system of health administration in all country and suburban municipalities which would be controlled by the state government health department. They specifically referred to the system of baby clinics already established in New South Wales and their benefits. In emphasising the necessity of clinics, they pointed to the fact that during 1915, 9107 children died within their first year, and of these 3227 or 35% died within the first week of life. Such clinics should provide a service for expectant mothers as well as post-natal care and advice. They further advised that the government conduct an experiment by establishing a clinic in one selected area first.(Crockett:3: VPRS 9291P1/17/T/6, pp 38, 40) There was evidently no immediate response to the committee’s advice.

The following year, in May 1917, three women in a voluntary capacity opened the first baby health clinic in Victoria in a shop front offered by Richmond Council. By 1918 a voluntary body, the Victorian Baby Health Centres Association had been formed to oversee and affiliate new centres now growing in number. The Public Health Dept offered little more than to pay half the salaries of qualified baby health centre sisters; local councils were expected to fund all other expenses. The State didn’t extend their interest until 1926 when they formed the Infant Welfare Section and appointed Dr Vera Scantlebury Brown as the first Director. In 1946 Dr W Barbara Meredith became Director of the Maternal and Child Hygiene Section of the Health Department. When she retired in 1960, Dr Alice E. (Betty) Wilmot remained in the position until 1976. That year the voluntary aspect of the service ceased and maternal and infant welfare combined with other local health service.

The early voluntary and municipal contributions, the tardy activity of the Health Department as well as its appointment of 3 women directors over a period of 50 years, all combined to influence the unique form of the early services in Victoria.

Purpose-built Baby Health Centres

The need to construct purpose-built baby health centre buildings was not an official priority in the early years of the movement. Most infant welfare organisations felt it more important to make municipal authorities aware of maternal and infant welfare concerns and to provide funding for nurses. More often known as depots, centres could be opened in any available accommodation which fitted their needs. Even in the 1960s some were still operating from R.S.L. quarters, and in municipal and church halls. The trend to having specific purpose-built centres began in 1926, in the wake of a report submitted to the Health Minister by Drs. Scantlebury and Main, although some centres existed before this date. Once it was evident that communities were intent on providing permanent accommodation for infant welfare activities, the VBHCA made some effort to ensure that suitable buildings were constructed (Crockett: 53). No subsidies were provided to councils by the government until 1948 (Crockett: 53), when 80,000 pounds were made available for grants towards the building of infant welfare and pre-school centres. However due to scarcity of materials and restrictions imposed by the Building Materials Control Acts which were not lifted until August 1952, very few buildings were erected immediately (Crockett: 59). Before the introduction of the government subsidy, only a few centres were council initiated or funded.

Many centres of this era (from the 1920s, to the baby boom period of the 1950s) no longer survive. The few that do, stand as memorials to the determination of local women, and collectively they are an enduring testimonial to the strength of the baby health centre movement in Victoria.

Summary dates:

1909 Talbot Milk Institute (charitable funding from grants)

1916 Committee report advises on setting up centres

May 1917 3 women open volunteer centre in Richmond

1918 Victorian Baby Health Centres Assoc. (voluntary)

1926 Vic govt forms Infant Welfare Section - Dr Scantlebury Brown

1926 First purpose-built centres open

1946 Dr Barbara Meredith - Director of Maternal & Child Hygiene Section of Health Dept

1948 Government introduces subsidies to councils to establish centres

1960 Dr Betty Wilmot, Director until 1976

HISTORY OF PLACE:

Coburg’s first baby health centre was established in reaction to the pneumatic influenza epidemic of 1919 which was probably brought back by troops returning from the war. Richard Broome’s history of the municipality, Coburg, Between Two Creeks, is a good source for information:

‘In all, 11 552 Australians died of pneumonic influenza; worldwide fatalities were estimated at twenty-one million, more than the number killed in the war. At Coburg there were 66 admissions and 2 deaths at the local hospital during the first wave and 306 admissions and 19 deaths during the second. An unknown number were ill at home, but medical authorities estimated that one third of the population fell ill. Coburg recorded the third-lowest suburban death rate from influenza due perhaps to the sparsely settled nature of the suburb. Dr Wallace and the hospital staff who laboured eighteen hours a day played their part. A grateful Council gave Wallace *100, Mitchell *10 and Miss Dyall, supervisor of the hospital kitchen, *5 bonus.

In response to the emergency, a group of people met at Mrs J. H. Ward’s house at 25 Victoria Street in mid-April 1919, to form a branch of the Royal Victorian Trained Nurses’ Association. One hundred members, each contributing five shillings, guaranteed the nurse’s salary, and nurse Wooton was on the job within three weeks. Mrs Whitham and Sister Holland lobbied the Council on behalf of the association and urged it to consider establishing a Truby King baby health centre, as the district had too many infant deaths for a suburb without slums. Dr (later Sir) Frederick Truby King the New Zealand infant health specialist, had recently been summoned by King George V to demonstrate his system of care in England. Victoria as yet had no Truby King centre, although infant welfare centres had been established in 1917. When the first Australian nurse trained in these New Zealand methods became available in October 1919, the Coburg branch of the Trained Nurses’ Association lobbied the Council which, after grumbling about its debts, voted six to three to set aside *200 for a nurse’s salary and rent, thereby making Coburg the first Truby King centre in Victoria.

The centre was opened on 4 December 1919 by Dr King, in the presence of the Governor-General’s wife, Lady Munro Ferguson, and a host of medical and civic dignitaries. King’s rather eccentric claims were that the essentials of healthy infant development comprised ‘a capacious jaw, furnished later with sound teeth, and a large nasal cavity’. He spoke strongly against bottle feeding, adding: ‘The aboriginals both here and in New Zealand were infinitely better equipped in the directions he had mentioned than the cultured inhabitants’. Lady Munro Ferguson spoke and two students from Heatherton College, South Yarra, used dolls to demonstrate bathing, dressing and child care. The centre, at 336a Sydney Road east, had a ‘home-like, restful room, opening onto a wide balcony 30 feet long; two ante-rooms, bath-room, kitchen, and an attractive playground’. On the wall was the motto: ‘Pure Air and Sunshine is as Necessary for babies as for plants’. The centre attracted many visits from those interested in infant health.

The centre opened initially part-time, but after August 1922 was open every afternoon, leaving mornings for home visiting. The Moreland school girls attended once a week for instruction in child care. The centre stressed breast feeding, advised mothers who had feeding difficulties and gave expert advice on artificial feeding. The cost of Willsmere milk forced some mothers to use local, non-bottled, non-pasteurised milk. Sister Kirkland instructed them in the ‘humanizing’ of this milk at home (the modification of cow’s milk by the additions of water, sugars and fats). Her methods were adapted to ‘the ordinary house facilities of a not wealthy suburb, no ice chest, but ordinary water, or “kerosene tin” coolers or bran boxes’. The results were said to be excellent and in the first year there were no deaths among the infants attending the centre.

Increasing popularity and a growing population led to overcrowding at the Truby King centre. By February 1925 Sister Duff reported to the management committee that on ‘some afternoons, mothers have to stand and wait until someone leaves the room. The room is not large enough to allow any more chairs. If the attendance of mothers increases the room will require expanding’. On 24 July 1926 a new brick centre was opened in Elm Grove which still tends the infants of Coburg to this day’ (Broome: 197-98).

Mayor Cr. J. Robinson JP opened the centre. Sir Truby King had laid the foundation stone in October 1925. Designed by architect, R. McC. Dawson, the new red brick bungalow style building was the first purpose-built Truby King centre in Victoria. The local Coburg City Band shared the premises.

The Truby King Movement

In September 1920, the Society for the Health of Women and Children of Victoria (SHWC), often known as the Truby King Society, was set up in Victoria. It adopted the baby care methods promoted by Dr Truby King. Similar in aim to the Victorian Baby Health Care Association (VBHCA), it too, developed its own training school, and methods which became known as the ‘Plunket Nursing System’. It also opened centres, with the Coburg example of 1919 pre-dating the actual formation of the Society.

Crockett writes, ‘King had set himself up as an expert in infant welfare in New Zealand at a time when New Zealand led the world in containing the incidence of infant mortality. Indeed, in 1918, the VBHCA examined and considered, but later dismissed the ‘Plunket Nursing System’. Doctors in Australia for the most part were singularly unimpressed by King’s ‘charismatic character’, his exhortations for strict routine, and his expensive and complicated formula for humanized milk which they deemed to be fat-rich but protein-deficient. The VBHCA had studied ideas in North America, England and New Zealand before deciding to ignore King’s methods, instead choosing other expert opinions to develop a system which they believed suited the complex conditions affecting the mother and baby in Australia, to honour the individual rather than adhere to strict feeding and disciplinary codes’.

‘In spite of their similar objectives, therefore, a great deal of antipathy and competition developed between the two societies’ (Crockett: 18). ‘Truby King supporters had produced a major coup against the VBHCA ... by being the first to construct a purpose built training hospital - the Tweddle Baby Hospital - in 1923, but wherever they gained a stronghold in the suburbs, especially in the Footscray and Dandenong regions, purpose built buildings were soon in evidence’ (Crockett: 53).

Notes by Frances O'Neill on Baby Health:

The health of mothers and babies at birth and in the first years of infant life was of increasing concern in the first years of the twentieth century. In 1917 the first baby health centre was opened in Richmond. The Victorian Baby Health Centres association was formed the following year to form and organise new centres and their voluntary committees.. The Society for the Health of Women and Children of Victoria (Plunket Society) commenced shortly afterwards. The no of centres of trained infant welfare nurses and of mothers and infants attending centres grew rapidly.

At the same time, infant and maternal mortality declined. The State formed an Infant Welfare Section of the Public Health Department and appointed Dr Vera Scantlebury Brown as the first Director in 1926. Maternal and child welfare services have become part of community health services in Victoria and the voluntary aspect has disappeared.

The early purpose built infant welfare centre buildings were initially funded by voluntary activity. Before 1949 no government subsidies were provided for these buildings, Only a few were council funded.

The most important buildings are those built before 1950 as they were community funded and built sometimes with voluntary labour.

BABY HEALTH CARE CENTRE - Permit Exemptions

General Exemptions:General exemptions apply to all places and objects included in the Victorian Heritage Register (VHR). General exemptions have been designed to allow everyday activities, maintenance and changes to your property, which don’t harm its cultural heritage significance, to proceed without the need to obtain approvals under the Heritage Act 2017.Places of worship: In some circumstances, you can alter a place of worship to accommodate religious practices without a permit, but you must notify the Executive Director of Heritage Victoria before you start the works or activities at least 20 business days before the works or activities are to commence.Subdivision/consolidation: Permit exemptions exist for some subdivisions and consolidations. If the subdivision or consolidation is in accordance with a planning permit granted under Part 4 of the Planning and Environment Act 1987 and the application for the planning permit was referred to the Executive Director of Heritage Victoria as a determining referral authority, a permit is not required.Specific exemptions may also apply to your registered place or object. If applicable, these are listed below. Specific exemptions are tailored to the conservation and management needs of an individual registered place or object and set out works and activities that are exempt from the requirements of a permit. Specific exemptions prevail if they conflict with general exemptions. Find out more about heritage permit exemptions here.Specific Exemptions:General Conditions: 1. All exempted alterations are to be planned and carried out in a manner which prevents damage to the fabric of the registered place or object. General Conditions: 2. Should it become apparent during further inspection or the carrying out of alterations that original or previously hidden or inaccessible details of the place or object are revealed which relate to the significance of the place or object, then the exemption covering such alteration shall cease and the Executive Director shall be notified as soon as possible. General Conditions: 3. If there is a conservation policy and plan approved by the Executive Director, all works shall be in accordance with it. General Conditions: 4. Nothing in this declaration prevents the Executive Director from amending or rescinding all or any of the permit exemptions. General Conditions: 5. Nothing in this declaration exempts owners or their agents from the responsibility to seek relevant planning or building permits from the responsible authority where applicable. Exterior

1.Minor repairs and maintenance which replace like with like.

2. Removal of extraneous items such as air conditioners, pipe work, ducting, wiring, antennae, aerials etc, and making good.

3. Installation, removal or replacement of garden watering systems, provided the installation of the watering systems do not cause short or long term moisture problems to the building.

4. Resurfacing works to carpark.Interior

1.Minor repairs and maintenance which replace like with like.

2. Painting of previously painted interior surfaces provided that preparation or painting does not remove evidence of the original paint or other decorative scheme.

3. Installation, removal or replacement of carpets and/or flexible floor coverings, eg vinyl.

4. Installation, removal or replacement of curtain track, rods, blinds and other window dressings.

5. Installation, removal or replacement of hooks, nails and other devices for the hanging of mirrors, paintings and other wall mounted artworks.

6. Refurbishment of bathrooms and toilets including removal, installation or replacement of sanitary fixtures and associated piping, mirrors, wall and floor coverings.

7. Installation, removal or replacement of kitchen benches and fixtures including sinks, stoves, ovens, refrigerators, dishwashers etc and associated plumbing and wiring.

8. Installation, removal or replacement of electrical wiring provided that all new wiring is fully concealed.

13. Installation, removal or replacement of bulk insulation in the roof space.

14. Installation, removal or replacement of smoke detectors.15. Installation, removal or replacement of electronic security systems

BABY HEALTH CARE CENTRE - Permit Exemption Policy

It is the purpose of the permit exemptions to allow works that do not impact on the significance of the place to occur without the need for a permit.

-

-

-

-

-

INFANT BUILDING AND SHELTER SHED, PRIMARY SCHOOL NO.484

Victorian Heritage Register H1709

Victorian Heritage Register H1709 -

COTTAGE

Victorian Heritage Register H0689

Victorian Heritage Register H0689 -

BRIDGE

Victorian Heritage Register H1446

Victorian Heritage Register H1446

-

'YARROLA'

Boroondara City

Boroondara City -

1 Bradford Avenue

Boroondara City

Boroondara City

-

-