WOODHOUSE-NAREEB SOLDIERS MEMORIAL HALL

2073 BUNDORAN LANE GLENTHOMPSON, SOUTHERN GRAMPIANS SHIRE

-

Add to tour

You must log in to do that.

-

Share

-

Shortlist place

You must log in to do that.

- Download report

Statement of Significance

What is significant?

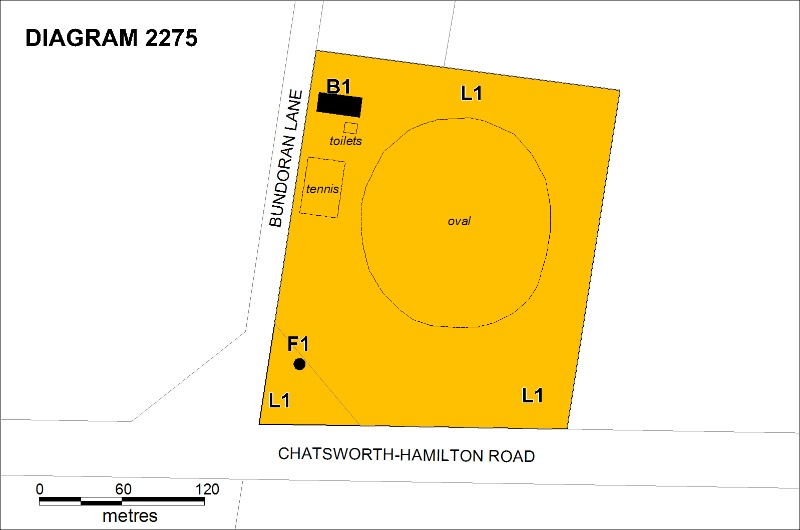

The Woodhouse-Nareeb Soldiers Memorial Hall is a large corrugated iron-clad hall in a rural setting east of Hamilton. The hall was designed by the architect Stewart Handsaay and built in 1955 as a memorial to local servicemen who died in World War II. It was funded by the local community of soldier settler families who came to the area under the World War II Soldier Settlement Scheme, developed to help in the rehabilitation of returned servicemen. More diggers were settled under the Victorian scheme than in any other state, and the Western District area was a major focus of soldier settlement. The Soldier Settlement Commission compulsorily acquired 65 blocks of land in the area from seven large pastoral properties, including Woodhouse and Nareeb Nareeb. The difficulties of clearing, fencing and developing farms on their land and raising families under primitive conditions and with only the help of other settler families led to a strong sense of community. A meeting was held in 1950 to form a committee to raise funds to build a community hall at Woodhouse. The hall was officially opened on 18 September 1955 and dedicated by Sister Vivian Bullwinkel, the only survivor of the 1942 massacre of Australian army nurses by the Japanese at Banka Island. A memorial planting of Canary Island Pines was begun at the southern end of the site in 1954, tennis courts and a cricket ground were built about 1959, and the hall was extended in 1967. After fire threatened the Memorial Plantation in 1977 it was decided to build a Memorial Cairn, as a more permanent reminder of those who had died in the war and of the origins of the community as a soldier settlement. A cairn of local stone, designed by the architect N M Griffin, was built in 1978 by G O E Behnke & Sons of Penshurst next to the main Hamilton-Chatsworth Road.

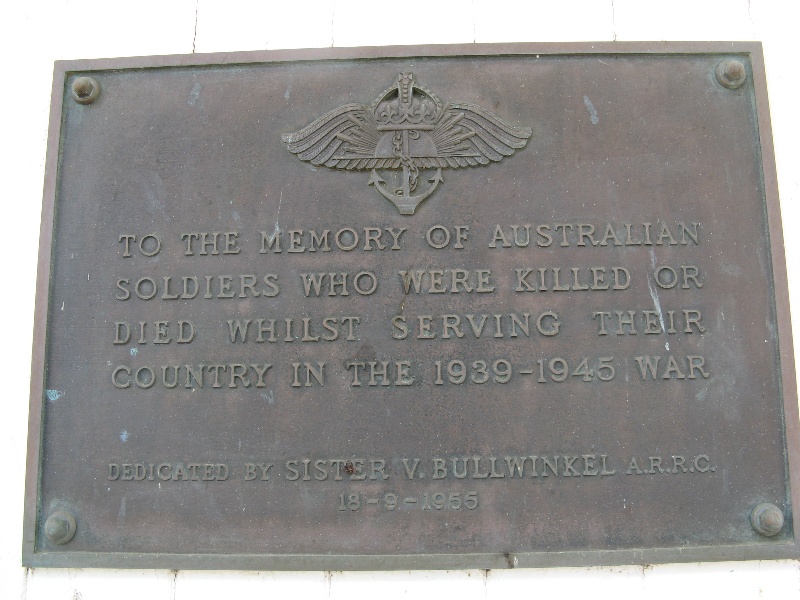

The Wooodhouse-Nareeb Soldiers Memorial Hall is a substantial timber-framed hall clad with timber on the front facade and with corrugated iron on the other sides and with a corrugated iron roof. It is a simple utilitarian structure but is distinctive for its use of modernist detailing in the sloping windows along each side and the row of windows above the entrance, and for the gabled front portico formed by an extension of the roof line. On the front wall is a bronze plaque commemorating soldiers killed in WWII. Adjacent to the hall are tennis courts, a sports oval and a plantation in memory of servicemen and of local families.

This site is part of the traditional land of the Wathaurung people.

How is it significant?

The Woodhouse-Nareeb Soldiers Memorial Hall is of historical significance to the state of Victoria.

Why is it significant?

The Woodhouse-Nareeb Soldiers Memorial Hall is historically significant for its association with the successful post-WWII Soldier Settlement scheme developed by the Federal Government to aid the rehabilitation of returned soldiers. The scheme, which operated from 1945 until 1962, was particularly successful in Victoria, where thousands of diggers were settled on farms, more than in any other state. The hall is an unusual example of a community facility constructed by soldier settler families in the Western District, which was a major focus of soldier settlement in the state. It demonstrates the sense of community and co-operative spirit that developed amongst the soldier settler families due to the difficulties faced by them in establishing their farms. The dedication of this key community building as a war memorial is a tangible reminder of the profound impact of war on Victorian communities.

-

-

WOODHOUSE-NAREEB SOLDIERS MEMORIAL HALL - History

CONTEXTUAL HISTORY

Post-WWII Soldier settlement in Victoria

[Information from Pat Giles, Swords into ploughshares. The story of soldier settlement: Woodhouse-Nareeb-Chatsworth House Hopkins Hill and Yamba East Estates, Hamilton 1992 [1985]; and Rosalind Smallwood, Hard to go Bung. World War II Soldier Settlement in Victoria 1945-62, South Yarra 1992.]

At the end of WWII the Australian Government saw the need to undertake a rehabilitation program to retrain ex-servicemen, so that they could resume their place in civilian life. Many men had enlisted at age 18, and had had no chance to qualify for any civilian career, so the Government set up various assistance programs to enable men to gain qualifications, buy houses and establish businesses.

In 1946 the Victorian Government set up the Soldier Settlement Commission under the Soldier Settlement Act. Under the Act the Commission was given the power to acquire land from private landholders and set apart suitable areas of Crown Land. This was subdivided into holdings considered sufficient for efficient operation of a farm.

The object of the Commission was to develop and improve each holding to the stage where it could be brought into production by the settler in a reasonable time. This included the erection of a house, farm structures, fencing and water supply.

Applicants were classified for suitability by the Commission on the basis of length of service, farming experience, personal attributes, evidence of financial responsibility and marital status, and personal interviews were conducted. Where possible the settler was expected to contribute towards the purchase of stock, plant and equipment but could obtain financial assistance from the Commission if required. Repayment was by instalments and Freehold Title was obtained on completion of repayments, but not within less than six years.

Under this scheme 545 Victorian properties (a total of 1,193,171 acres) were acquired by the Soldier Settlement Commission, plus 40,000 acres of former Crown land, and 1,180,669 acres of the total area was subdivided into 3,048 Soldier Settlement blocks. It included some of the best land in Victoria. The scheme was particularly successful in Victoria compared to other states, with Victoria settling more WWII diggers than any other state - almost half of the national total of 12,036.

When ready for settlement subdivisions were advertised in the newspapers, eligible servicemen applied and were given maps of the areas, were able to view the blocks, and submit applications in order of preference. Decisions were made after interviews, and successful applicants advised by mail.

The Commission was particularly anxious to avoid the mistakes of the disastrous post-WWI Soldier Settlement scheme, when more than half of the farms had failed. It set the debt level and equity at a level that enabled the settlers to make a reasonable living.

WWII soldier settlement schemes involved more careful planning. Holdings were larger and there was an expansion of intensively cultivated irrigation blocks. Infrastructure was improved, while roads, fencing, houses, crop material and information were supplied to prospective farmers in a thought-out way that involved co-operation between the farmers and supervisors of the scheme.

The terms were generous as the government paid each settler a living wage of £9 a week until the block came into production. He was given a temporary lease at a nominal rent, which would increase when the house, sheds and water supply were finished. Once fencing was completed, and pastures established, he was able to put on a stipulated number of stock, machinery and working plant. When the block was developed, the settler was given a year to consolidate his position, during which time he was not charged rent or agistment, and was paid a living allowance. At the end of the year, the Commission's valuers valued the block, and then the settler was charged an annual rent. About a year later, he received an interim lease that determined the actual value. That lease ran for 3-4 years when finally the settler was given a purchase lease for 55 years at a very low rate of interest.

The size of the blocks varied in different areas varied: those in the Western District, intended for grazing, were up to 1800 acres. Only large properties, valued at more than £1500, could be compulsorily acquired, with priority given to land about to be sold, deceased estates owned by absentee landlords, or land which was underutilized.

The introduction of modern pasture improvement practices enabled great increases in the productivity of the land, and the scheme resulted in a great boost in Victoria's primary production, which more than doubled.

Conditions on the farms were at first very primitive, but a great community spirit appeared from the beginning, as the diggers helped each other to develop their blocks. There was at first little socialising, as money was tight, transport was limited and there was much work to be done, but this gradually changed. Many settlers became active in community organisations, such as the CFA, churches, sporting clubs, the Red Cross, CWA, etc. In many areas, particularly the more self-contained and remote ones, if the diggers and their families wanted facilities like local halls, tennis courts, clubrooms and even hospitals, they had to use their own facilities to build them.

The changing nature of war memorials post-WWII

[Information from Inglis, Sacred Places]

After WWI there was considerable debate about what constituted a fitting memorial to those who had served and died. Although people in most places preferred monumentality over use, halls were a common RSL preference. At that time of every hundred war memorials about twenty were halls, one or two were hospitals, schools or other functional forms, eighteen were both monumental and useful and the others were monuments. (pp 134-7) The hall was the most common of the utilitarian memorials. It was often used as a clubroom for returned soldiers and also as a community centre, especially in regions of post-war soldier settlement (p 147).

Following WWII monuments were out of fashion, and there was a decided preference for utility. C E W Bean founded a Parks and Playground Movement, which proposed recreation areas as suitable memorials. The RSL also expressed clear sympathy for the utilitarian and was against 'statues and such like'. It commented that 'if our fallen died that we might live, and have life more abundantly, they cannot adequately be commemorated in the cold bronze statue or the lifeless monument of yesterday'. (p 335)

Some towns and suburbs acquired war memorial centres, a complex of amenities rather than just a hall, and also swimming pools. These were not always obvious as a memorial.

HISTORY OF PLACE

The Soldier Settlement Commission compulsorily acquired portion of the pastoral stations Chatsworth House, Hopkins Hill and Nareeb Nareeb for soldier settlement towards the end of WWII. Blocks were allocated in later 1948 and early 1949. The Commission also purchased Woodhouse Station, with the exception of that portion known as Woodhouse West, which was taken over by the former Station manager, and these blocks were allocated around the same time. Yamba East was not opened for settlement until 1952. These stations lost roughly one-third of their total acreage. The pastoral property Woodhouse yielded 25 blocks for soldier settlement, Nareeb 11 blocks, Chatsworth House 15 blocks and Hopkins Hill 7 blocks.

The men came onto their blocks first, fencing and clearing rabbits until the corrugated iron garages were built, when the family generally moved in. Conditions were very primitive for a number of years. Problems came from the isolation and lack of transport, loneliness, and also the number of rabbits, which were in plague proportions at the time. Poison baits were laid, and rabbit drives were organised, which killed thousands and also served to raise funds for local community organisations.

Settlers on the estates came from a variety of civilian backgrounds but were bonded by their common service experience. Mutual support was essential in accomplishing many of tasks on the farms, and there was a very strong sense of community, also forced upon the people by geography and circumstances.

Community organisations were essential in contributing to and supporting the community and a number were quickly formed: the first was the RSL (1949), in 1949 the Woodhouse Fire Brigade, followed by the CWA (1950) and later the Red Cross (1952), Scouts and Cubs (1958).

In April 1950 43 people attended a meeting at McAllister's woolshed to form a committee to raise funds to build a community hall. A subscription list was opened and a Woodhouse Public Hall account was opened with an amount of £31/4/-, mainly proceeds from a dance. The first fund raising event was the raffle of a pressure cooker at one shilling a ticker.

The committee applied for a grant from the Department of Public Works and requested the Soldier Settlement Commission to revert the lease of the Nareeb Recreation Area back to the Crown Land Department for the purpose of a public hall. Funds were raised from rabbit drives, Tatts tickets, donations of fleeces, calf sales, raffles and woolshed dances.

In December 1951 the RSL contacted Stawell Timber Industries for information about a building suitable for a public hall and to be used in the meantime as RSL clubrooms.

At a meeting in 23 January 1952 it was decided to engage Stewart Handsaay as an architect, and quotations were called for the building. The successful tenderer was Strachan & Co of Hamilton with an amount of £2,604/5/-, later raised to £2,839. Architects fees were £78/2/6 plus extras.

A working bee cleared the recreation reserve of stones, and the Shire laid out and graded a playing area which was then cropped. Work began on the hall in March 1955. In September 1954 a memorial planting of Canary Island pines was planted at the Reserve and local people invited to dedicate a tree to the memory of a friend or relative killed in the recent war. Trees were also planted in memory of Army nurses who died in the Banka Island massacre of Japanese prisoners of war, and of those who lost their lives when the hospital ship Centaur was torpedoed.

At the official opening of the hall on 18 September 1955 six hundred people saw Sister Vivian Bullwinkel, the sole survivor of the Banka Island massacre, dedicate the hall, and Sister Betty Jeffrey, the author of the book White Coolies, an account of her POW experiences, dedicated the Memorial Plantation. S Routley, acting State President of the RSSAILA, preformed the official opening of the hall. An opening ball was held on 30 September, and from, then on balls were an almost a monthly event, held by the Hall Committee, the CWA, Red Cross, etc.

Tennis courts were built about 1959 and the Nareeb Tennis Club was very active for a number of years. A cricket pitch was laid down around 1959, but the cricket club lapsed in 1965 because of a shortage of players. A sewered toilet block was built later.

After the receipt of a Government grant of £3,729 the clubhouse was extended in 1967, with the addition of stage and two cloakrooms. Heating was installed in 1974.

The hall has always been the heart of the Settlement community, as the venue for meetings, balls and dances, birthday parties, indoor bowls and cards, Church and Sunday School, concerts, dinners and conferences. It has been used as a polling booth, for picture nights, CWA craft exhibitions, flower shows and the annual children's Christmas tree.

After fire threatened the Memorial Plantation in 1977 it was decided to build a Memorial Cairn, as a more permanent reminder of those who had died in the war. A public appeal supplemented a Government grant, and the architect N M Griffin was asked to submit a design. The cairn, made of local stone, was built, next to the main Hamilton-Chatsworth Road, by G O E Behnke & Sons of Penshurst. The Patrons were Sisters Betty Jeffrey, Sir Edward 'Weary' Dunlop, Colin Keon Cohen (State President of the RSL) and Sandford Begg and family, who attended at the service on 5 November 1978, when Sister Betty Jeffrey (who in 1955 dedicated the memorial plantation) dedicated the Memorial.

The Memorial Plantation includes trees planted in memory of former soldiers as well as local families. They were planted during the 1960s-1980s.

WOODHOUSE-NAREEB SOLDIERS MEMORIAL HALL - Assessment Against Criteria

a. Importance to the course, or pattern, of Victoria's cultural history

The Woodhouse-Nareeb Soldiers Memorial Hall is historically significant for its association with the successful post-WWII Soldier Settlement scheme, developed to aid the rehabilitation of returned soldiers. The scheme, which operated from 1945 until 1962, was particularly successful in Victoria, where thousands of diggers were settled on farms, more than in any other state. It is an unusual example of a community facility constructed by soldier settler families in the Western District, which was a major focus of soldier settlement in the state. It demonstrates the sense of community and co-operative spirit that developed amongst the soldier settler families due to the difficulties faced by them in establishing their farms. The dedication of this key community building as a war memorial is a tangible reminder of the profound impact of war on Victorian communities.

b. Possession of uncommon, rare or endangered aspects of Victoria's cultural history.

c. Potential to yield information that will contribute to an understanding of Victoria's cultural history.

d. Importance in demonstrating the principal characteristics of a class of cultural places or environments.

e. Importance in exhibiting particular aesthetic characteristics.

f. Importance in demonstrating a high degree of creative or technical achievement at a particular period.

g. Strong or special association with a particular community or cultural group for social, cultural or spiritual reasons. This includes the significance of a place to Indigenous peoples as part of their continuing and developing cultural traditions.

h. Special association with the life or works of a person, or group of persons, of importance in Victoria's history.

The Woodhouse-Nareeb Soldiers Memorial Hall has close associations with post- WWII soldier settlers, and their families, who were able to buy farms in this area as part of their rehabilitation after WWII.

WOODHOUSE-NAREEB SOLDIERS MEMORIAL HALL - Plaque Citation

This hall was built in 1955 by the local community of soldier settlers, who came here under the successful Soldier Settlement Scheme developed by the Federal Government to aid the rehabilitation of returned soldiers after World War II.

WOODHOUSE-NAREEB SOLDIERS MEMORIAL HALL - Permit Exemptions

General Exemptions:General exemptions apply to all places and objects included in the Victorian Heritage Register (VHR). General exemptions have been designed to allow everyday activities, maintenance and changes to your property, which don’t harm its cultural heritage significance, to proceed without the need to obtain approvals under the Heritage Act 2017.Places of worship: In some circumstances, you can alter a place of worship to accommodate religious practices without a permit, but you must notify the Executive Director of Heritage Victoria before you start the works or activities at least 20 business days before the works or activities are to commence.Subdivision/consolidation: Permit exemptions exist for some subdivisions and consolidations. If the subdivision or consolidation is in accordance with a planning permit granted under Part 4 of the Planning and Environment Act 1987 and the application for the planning permit was referred to the Executive Director of Heritage Victoria as a determining referral authority, a permit is not required.Specific exemptions may also apply to your registered place or object. If applicable, these are listed below. Specific exemptions are tailored to the conservation and management needs of an individual registered place or object and set out works and activities that are exempt from the requirements of a permit. Specific exemptions prevail if they conflict with general exemptions. Find out more about heritage permit exemptions here.Specific Exemptions:General Conditions: 1. All exempted alterations are to be planned and carried out in a manner which prevents damage to the fabric of the registered place or object. General Conditions: 2. Should it become apparent during further inspection or the carrying out of works that original or previously hidden or inaccessible details of the place or object are revealed which relate to the significance of the place or object, then the exemption covering such works shall cease and Heritage Victoria shall be notified as soon as possible. General Conditions: 3. If there is a conservation policy and plan, all works shall be in accordance with it. Note: A Conservation Management Plan or a Heritage Action Plan provides guidance for the management of the heritage values associated with the site. It may not be necessary to obtain a heritage permit for certain works specified in the management plan. General Conditions: 4. Nothing in this determination prevents the Executive Director from amending or rescinding all or any of the permit exemptions. General Conditions: 5. Nothing in this determination exempts owners or their agents from the responsibility to seek relevant planning or building permits from the responsible authorities where applicable. Minor Works : Note: Any Minor Works that in the opinion of the Executive Director will not adversely affect the heritage significance of the place may be exempt from the permit requirements of the Heritage Act. A person proposing to undertake minor works must submit a proposal to the Executive Director. If the Executive Director is satisfied that the proposed works will not adversely affect the heritage values of the site, the applicant may be exempted from the requirement to obtain a heritage permit. If an applicant is uncertain whether a heritage permit is required, it is recommended that the permits co-ordinator be contacted.WOODHOUSE-NAREEB SOLDIERS MEMORIAL HALL - Permit Exemption Policy

The purpose of the Permit Policy is to assist when considering or making decisions regarding works to the place. It is recommended that any proposed works be discussed with an officer of Heritage Victoria prior to making a permit application. Discussing any proposed works will assist in answering any questions the owner may have and aid any decisions regarding works to the place. It is recommended that a Conservation Management Plan is undertaken to assist with the future management of the cultural significance of the place.

The extent of registration protects the whole site. The addition of new buildings to the site may impact upon the cultural heritage significance of the place and requires a permit. The purpose of this requirement is not to prevent any further development on this site, but to enable control of possible adverse impacts on heritage significance during that process. All of the registered building is integral to the significance of the place and any external or internal alterations are subject to permit application.

-

-

-

-

-

NAREEB NAREEB HOMESTEAD COMPLEX

Southern Grampians Shire

Southern Grampians Shire -

WOODHOUSE-NAREEB SOLDIERS MEMORIAL HALL COMPLEX

Southern Grampians Shire

Southern Grampians Shire -

Woodhouse-Nareeb Soldiers Memorial Hall Complex

Vic. War Heritage Inventory

Vic. War Heritage Inventory

-

153 Morris Street, Sunshine

Brimbank City

Brimbank City -

186-188 Smith Street

Yarra City

Yarra City -

1ST STRATHMORE SCOUT HALL (FORMER)

Moonee Valley City

Moonee Valley City

-

-