Back to search results

KAY STREET INFILL HOUSING

77 KAY STREET CARLTON, MELBOURNE CITY

KAY STREET INFILL HOUSING

77 KAY STREET CARLTON, MELBOURNE CITY

All information on this page is maintained by Heritage Victoria.

Click below for their website and contact details.

Victorian Heritage Register

-

Add to tour

You must log in to do that.

-

Share

-

Shortlist place

You must log in to do that.

- Download report

2024 Kay Street Infill Housing

On this page:

Statement of Significance

What is significant?

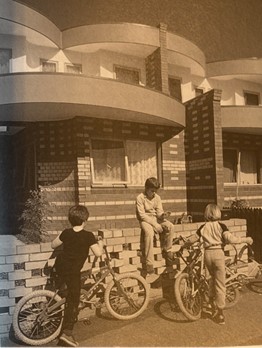

The townhouse pair at 77 Kay Street, designed by Peter Corrigan of Edmond and Corrigan for the Ministry of Housing infill program in 1982 and constructed from 1982-83. Significant features include, but are not limited to, the exterior form, materials, and colouring; hit-and-miss cream brick fence; the bi-chrome brickwork; set-back from the street and prominent awnings. Significant characteristics of the interior include exposed face brickwork and provision of ample natural light.

How is it significant?

The Kay Street Infill Housing is of historical, architectural and aesthetic significance to the State of Victoria. It satisfies the following criterion for inclusion in the VHR:

Criterion A

Importance to the course, or pattern, of Victoria’s cultural history.

Criterion D

Importance in demonstrating the principal characteristics of a class of cultural places and objects.

Criterion E

Importance in exhibiting particular aesthetic characteristics.

Criterion A

Importance to the course, or pattern, of Victoria’s cultural history.

Criterion D

Importance in demonstrating the principal characteristics of a class of cultural places and objects.

Criterion E

Importance in exhibiting particular aesthetic characteristics.

Why is it significant?

The Kay Street Infill Housing at 77 Kay Street, Carlton is historically significant as evidence of the innovative approach to public housing in Victoria in the late 1970s and early 1980s. It demonstrates the radical change in public housing policy from the high-rise developments of the 1950s, 60s and 70s under the Ministry of Housing’s ‘New Directions’ policy. The townhouse pair was used to convey the success of the Ministry’s new programs and became emblematic of its optimism in the era. The Ministry’s new approach, which was intended to produce homes that were more creative and humane, of a higher standard, integrated into their contexts, and free of the stigma associated with public housing developments, is clearly demonstrated in the subject dwellings.

(Criterion A)

The Kay Street Infill Housing is architecturally significant as a notable example of infill public housing in Victoria. It was one of the most architecturally adventurous of the infill residences commissioned by the Ministry of Housing in the 1980s and was widely documented and reviewed. It is a modest yet important work of the eminent architectural practice Edmond and Corrigan (Maggie Edmond and Peter Corrigan) and reflects their confidence and proficiency in exploring a pluralist approach to architecture in Victoria and pronounced interest in the built character of suburbia. The residences were recognised by a Royal Australian Institute of Architects (Victorian Chapter) award for Outstanding Architecture, New Housing category in 1985. The infill program as a whole was recognised with an award for Enduring Architecture in 2010.

(Criterion D)

The Kay Street Infill Housing is aesthetically significant for its distinctive design characteristics which have been frequently referenced and celebrated in creative and cultural works. Its form, use of colour and choice of materials are highly distinctive and photographs of the residences were often used by the Ministry of Housing to promote its own work. The residences have been strikingly photographed for magazines, artworks and books and the repeated use of images of the Kay Street townhouses emphasises their widespread recognition.

(Criterion E)

Show more

Show less

-

-

KAY STREET INFILL HOUSING - History

Establishment of the Housing Commission of Victoria

The early twentieth century saw increasing concern about housing and living conditions in inner-city Melbourne. Emerging ideas about health, welfare and town planning coalesced around anxieties about inner-city housing. A range of community leaders called for action on the issue of clearing overcrowded ‘slum areas’ and providing low-cost housing. These calls intensified as the problem worsened during the Depression. After ‘slum abolition’ became a major issue at the 1935 election, the Housing Act of 1937 was passed and the Housing Commission was established. Its aims were the improvement of existing housing conditions via reclamation and redevelopment, and the provision of rental accommodation for people with limited incomes. The formation of the Commission was the first time the Victorian Government had assumed primary responsibility for the provision of adequate and suitable housing for people living in poverty. The Experimental Concrete Houses in Port Melbourne are significant as the first pair of houses produced by the newly formed Commission and are included in the VHR (H1863).

Urban renewal and high-rise development

The 1950s saw a severe housing shortage created by a rapid population increase. In this context, ‘slum reclamation’ re-emerged as a priority for the Commission. From 1956 to 1974, the Commission’s approach evolved into an expansive program of urban renewal and the replacement of large precincts in the inner city with high-density estates, often high-rise towers. Large areas of the inner suburbs were identified as centres of sub-standard housing and proposed for demolition and replacement with new housing developments. In 1956, the Housing Commission estimated that some 242 hectares of inner Melbourne were considered slums and needed to be cleared. In the 1960s, over 65 hectares of the inner suburbs were cleared for comprehensive redevelopment. By 1973, the Commission had constructed a total of 45 high-rise flat buildings across inner Melbourne.

Parallel to this period of substantial change, residents’ associations in inner-city suburbs mounted well-organised and effective protest campaigns. The 1960s and 1970s saw widespread public criticism of the Commission’s approach. It faced intense and successful opposition from residents of areas like Brookes Crescent in Fitzroy North, causing reclamation plans to be abandoned. Although the high-rises were intended to provide a cost-efficient solution to the post-war housing crisis, the Commission was criticised for disregarding the needs of communities and the character of historic inner-city areas. The Ministry of Housing would later reflect that:

‘It was thought that the housing crisis could be solved by using technology to provide shelter for masses of people. There was little understanding of the social and environmental impacts of this course of action.’

In response, the Commission completed construction on the last high-rise block in 1974. In the latter part of the 1970s, a range of alternatives were pursued, including housing developments on the urban fringe which led to the Commission being examined for unscrupulous land acquisition practices.

Ministry of Housing

After sustained public criticism of its operations, and several controversies leading to a Royal Commission, the Housing Commission underwent major reform in the late 1970s and ‘New Directions’ policies were implemented. Renate Howe writes that, ‘what was evident in the Commission from the late 1970s was enthusiasm for change.’ The Commission was merged into the Ministry of Housing which explicitly distanced itself from the Housing Commission and its poor reputation.

The Ministry of Housing committed to acting:

‘… as a creative, humane but efficient provider of housing services to the people, especially those who are in the greatest need and least able to help themselves … the Ministry should work in co-operation and consultation not only with other Government Departments and Local Government but also with its clients and interest community groups…With these guiding principles the Ministry has set its course for the eighties.’

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the Ministry of Housing developed several innovative programs that addressed a range of housing needs, declaring that:

‘The Ministry of Housing no longer builds large housing estates in the metropolitan area. Instead, we purchase and build houses which are spread throughout the community. The Ministry is developing programs and designs that cater for today’s clients, e.g. the elderly, single parent households, homeless youth and disabled persons.’

In 1982, the first Labor Government in Victoria in 27 years was elected. The Cain government’s investment in public housing almost doubled in the 1982/83 State budget, and the subsequent increase in funding assisted in expanding and developing new approaches.

The ‘Spot purchase’ program boosted public housing stock by purchasing existing individual dwellings in established suburbs and towns, while the Granny flat and dual occupancy programs sought to house a greater number of people in existing residences. The ‘Rehabilitation’ program focused on the recycling and upgrade of historic buildings in inner urban areas to provide accommodation (see, for example, the Emerald Hill Estate VHR H1136 and Glass Terrace, Fitzroy VHR H0446) while the ‘Urban homesteading’ and ‘Self build’ programs supported low-income owners into home ownership by supporting people to build their own homes or to repair an existing home.

As high-rises were the visible symbol of the Commission’s response to the post-war housing crisis, urban renewal and rehabilitation ‘signified an important change in direction of the Commission during its transition to becoming the Ministry of Housing’. The approach of the Ministry of Housing in this era received widespread recognition. In 1983, the Ministry became the first housing authority in Australia to win a national architecture award, receiving the Royal Australian Institute of Architecture’s award for innovative design involving the community. The award acknowledged the Ministry’s new approach to providing public housing and for taking a more ‘philosophical approach’ to the issue of public housing. In an article in The Architectural Review in 1985, the Ministry was described as having ‘one of the most enlightened public housing programmes anywhere’.

Infill Housing

‘Infill Housing’ formed an important part of this suite of new approaches, and had been utilised at sites like Brookes Crescent in Fitzroy, along with rehabilitation of housing stock ‘worthing or retention’, from the mid-1970s. The infill program was then expanded under the creative leadership of individuals such as John Devenish and Dimity Reed. Devenish in particular was responsible for engaging ‘some of the most notable and progressive architectural practices of the day’ to work on infill projects.’ Although the ‘slum clearance’ program had been abandoned, several areas of South Melbourne, Carlton, Fitzroy and Richmond that were previously designated as slum reclamation areas remained. All these areas included a mixture of houses that had been purchased by the Commission, cleared sites and privately owned houses. These locations became the focus of infill activities, where new residences would be designed to fit into the existing built fabric. The Ministry’s goals for the infill program were aspirational:

‘… only by reinstating the fine texture evident in urban areas can the damage caused by large scale development and subsequent coarsening of the urban fabric be repaired … Neighbourhoods are being revitalised through the rehabilitation of existing buildings and construction of new infill housing on under-utilised sites”

Infill housing was to be high-quality, work with the existing built environment, and provide tenants with privacy and amenity.

Infill designs became symbolic of the work of the Ministry in the era. Howe writes that ‘the Infill Housing Program was a major symbol of a new approach to housing design… rehabilitation and Infill programs had begun to surface as the image of public housing more generally’. The Ministry itself described the rehabilitation and infill program as ‘the most indicative of the Commission’s revised approach to urban reclamation.’ Although infill projects tended to be planned for inner urban areas, the approach was also used in middle-ring suburbs like Box Hill and in regional areas like Eaglehawk and Geelong.

In addition to using the Ministry’s own architects, it engaged established yet progressive architectural practices to produce designs for infill houses. The Ministry’s Annual Report for 1982-83 opened with a description of the Rehabilitation and infill program and a large photograph of the Kay Street Infill Housing, noting that the program:

‘… [has] continued to gain wide public recognition. The quality of designs produced by both our own architects and leading private firms has been consistently high. Our emphasis has been on good-quality housing, conveniently located, and sensitive to the pre-existing streetscape.’

From 1982-83 to 1986-87, 1078 medium-density family units were made available through rehabilitation of existing housing stock or creation of infill housing in the inner and middle suburbs of Melbourne, thanks in part to the funding boost delivered to the Ministry of Housing. The housing that is the result of that program won numerous local and national architectural awards and is ‘perhaps the most tangible illustration of the bold and innovative change in direction after the restructure of the old Commission into the Ministry of Housing’.

Kay Street reclamation area

The area around Kay, Station and Canning streets in Carlton, which had previously been identified for renewal, was selected for a program that combined rehabilitation of existing housing stock and spot infill. In 1979, a joint planning group was established which included the Ministry of Housing and Melbourne City Council. The building program commenced in 1980 and was scheduled for completion in 1982. Due to rising costs, the initial designs were abandoned. In 1982 it was reported that in response:

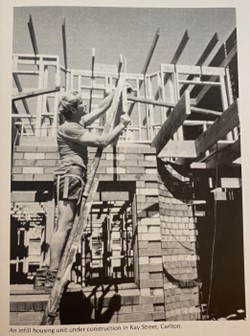

‘Four private architectural firms have been briefed to develop new and innovative schemes with a stringent cost limit for a number of these sites. Other schemes have been prepared by the Ministry’s own staff.’

Each architectural practice was given a small site that had been vacant or contained dilapidated housing and was invited to develop a design that responded specifically to the urban context. Edmond and Corrigan Architects (Maggie Edmond and Peter Corrigan) was commissioned to produce designs for 77 and 78 Kay Street while architects Peter Crone, Cocks and Carmichael, and Gregory Burgess designed several properties on Station Street, Kay Street and Canning Street. Designs for the balance of infill residences in the area were produced by the Ministry’s own architects. According to Maggie Edmond, the selected architects had shown a ‘proven ability to design not only with currency of architectural language but all of us had a few years of experience under our belt.’

The briefing documents for the project were highly detailed and required that the proposed scheme provide an:

‘… alternative to the institutionalised housing in 19th century residential areas of Inner Melbourne [and] provide the householder with an experience that is life enhancing and promotes optimism; an experience that is usually not allowed the poor in our society.’

The proposal was to be:

‘… sympathetic to the scale and massing of the existing neighbourhood whilst providing a high standard of amenity to residents, including usable and satisfying open space. The proposed scheme should not be “institutional”, or readily categorised as “public housing”.’

Maggie Edmond has reflected that ‘at the forefront of the whole project was to take away the stigma’ usually associated with public housing and ‘give occupants a sense they were taken seriously.’ Edmond describes the relationship between architects working on their own designs within the precinct as collegial. The designs produced by the private practice architects tended to be idiosyncratic in their design approach while confidently meeting the brief.

77 Kay Street, Carlton

Peter Corrigan’s design for 77 Kay Street appears to have emerged in the first half of 1982. Edmond describes Corrigan as having an ‘affinity with the suburban ethic’ and the design for Kay Street included multiple references to the built form of Melbourne’s suburbs in its bi-chrome brickwork, set back from the pavement and wing walls. Conrad Harmann notes that the brick colour and patterning was a clear ‘illustration of the close connection between Edmond and Corrigan’s colour usage and High Victorian surroundings, particularly churches in the area.’ The design has been interpreted as referencing not only Victorian and Federation-era residences, but also the homes created by post-war migrants in its use of vivid colours, solid awnings and hit and miss cream brick fence. Curves were a consistent feature of Corrigan’s work, and these were seen again in the double ‘neo-Baroque’ awnings of Kay Street. Edmond notes that it ‘sits very comfortably in the canon of the work that was done previously and after it…it has the same sense of liveliness of form that was also respectful to where it was.’

The tender for construction of 77 Kay Street was advertised in June 1982. Later that month, the contract was awarded to Cugara Builders, who had previously completed work for Edmond and Corrigan on the Resurrection Church and School and were highly regarded for their ‘honesty, pride in workmanship and…intelligence.’ Construction was underway in the second half of 1982 and completed in 1983. It continues to serve as government housing.

Popular and critical recognition

77 Kay Street was adopted as a symbol of the infill housing program and became emblematic of its success. It signalled a new direction for the Ministry of Housing towards humane, responsive and high-quality housing. It was highlighted in the Ministry’s internal and external publications, including in Annual Reports, on the cover of That’s Our House: a History of Housing in Victoria (1985) and in the book New Houses for Old: Fifty Years of Public Housing in Victoria 1938-1988 (1988).

Individual designs of the infill program were recognised via architectural awards. The infill designs of Peter Crone and Gregory Burgess were recognised with Royal Australian Institute of Architects (Victorian Chapter) Merit Awards in the new housing category in 1983 and 1984 respectively. In 1985, Edmond and Corrigan’s design for 77 Kay Street received the Outstanding Architecture Award (New Housing category) from the Royal Australian Institute of Architects (Victorian Chapter). As well as receiving widespread recognition at the time, the infill program has gone on to be recognised as an important moment in the history of public housing and the development of architecture in Victoria. In 2010, the program won the Royal Australian Institute of Architecture (Victoria) 25-Year Award for Enduring Architecture.

The striking aesthetic qualities of the residences at 77 Kay Street were featured in 1980s culture magazine Crowd. They were also captured by John Gollings, a prominent architectural photographer, initially for Italian architecture and design magazine Domus. One of Gollings’ images of 77 Kay Street is now held by the National Gallery of Victoria. The photographs appear most recently on the cover of Italy/Australia: Postmodern Architecture in Translation.

The group of Ministry of Housing infill dwellings in the Kay Street area have also been recognised in guides and studies. They are included in Philip Goad’s important architectural guide Melbourne Architecture. The group also forms one of 13 case studies in Homeward: The Thematic History of Public Housing in Victoria prepared by Context for the Department of Human Services in 2012 where it was identified as historically and architecturally significant. The potential state-level cultural heritage significance of the group was identified by the Survey of Post-War Built Heritage in Victoria prepared by Heritage Alliance for Heritage Victoria in 2008.

Edmond and CorriganMargaret (Maggie) Edmond and Peter Corrigan formed a partnership in the mid-1970s. The newly formed practice initially attracted attention for its churches, including the Chapel of St Joseph in Mont Albert North (VHR H2351) and Church of the Resurrection in Keysborough (VHR H2293). In contrast to the prevailing architectural trends, the designs for these churches drew upon and celebrated their suburban contexts. They featured the ‘brick, vivid colours, hipped-tile roofs, heavy proportions, concrete patios and open lawns’ of the dwellings that surrounded them and were familiar to their congregations. The patterned brickwork and use of curved shapes were seen in the early church projects and were often a feature of Corrigan’s designs. The Keysborough project involved the provision of housing for elderly parishioners, bringing the needs of housing tenants to the fore. Edmond also brought with her a deep interest in the issues of ‘slum reclamation’ and the provision of public housing from experience with the Brookes Crescent campaign and the development of a model for the area that would require minimal demolition and redevelopment.

Residential designs that ‘extended their suburban referencing’ were a consistent part of the partnership’s work, and came to be complemented by designs for TAFE’s and fire stations. Their most substantial and striking contribution to the Melbourne streetscape came in the form of RMIT’s Building 8, which presented a ‘tumultuous, enchanted folly’ to Swanston Street and received numerous accolades. Both Maggie Edmond and Peter Corrigan have been recognised with a Gold medal by the Australian Institute of Architects, and both have been awarded honorary doctorates. Maggie Edmond considers 77 Kay Street ‘a very important example of the work of the practice.’

KAY STREET INFILL HOUSING - Permit Exemptions

General Exemptions:General exemptions apply to all places and objects included in the Victorian Heritage Register (VHR). General exemptions have been designed to allow everyday activities, maintenance and changes to your property, which don’t harm its cultural heritage significance, to proceed without the need to obtain approvals under the Heritage Act 2017.Places of worship: In some circumstances, you can alter a place of worship to accommodate religious practices without a permit, but you must notify the Executive Director of Heritage Victoria before you start the works or activities at least 20 business days before the works or activities are to commence.Subdivision/consolidation: Permit exemptions exist for some subdivisions and consolidations. If the subdivision or consolidation is in accordance with a planning permit granted under Part 4 of the Planning and Environment Act 1987 and the application for the planning permit was referred to the Executive Director of Heritage Victoria as a determining referral authority, a permit is not required.Specific exemptions may also apply to your registered place or object. If applicable, these are listed below. Specific exemptions are tailored to the conservation and management needs of an individual registered place or object and set out works and activities that are exempt from the requirements of a permit. Specific exemptions prevail if they conflict with general exemptions. Find out more about heritage permit exemptions here.Specific Exemptions:The works and activities below are not considered to cause harm to the cultural heritage significance of the Kay Street Infill Housingsubject to the following guidelines and conditions:

Guidelines

- Where there is an inconsistency between permit exemptions specific to the registered place or object (‘specific exemptions’) established in accordance with either section 49(3) or section 92(3) of the Act and general exemptions established in accordance with section 92(1) of the Act specific exemptions will prevail to the extent of any inconsistency.

- In specific exemptions, words have the same meaning as in the Act, unless otherwise indicated. Where there is an inconsistency between specific exemptions and the Act, the Act will prevail to the extent of any inconsistency.

- Nothing in specific exemptions obviates the responsibility of a proponent to obtain the consent of the owner of the registered place or object, or if the registered place or object is situated on Crown Land the land manager as defined in the Crown Land (Reserves) Act 1978, prior to undertaking works or activities in accordance with specific exemptions.

- If a Cultural Heritage Management Plan in accordance with the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006 is required for works covered by specific exemptions, specific exemptions will apply only if the Cultural Heritage Management Plan has been approved prior to works or activities commencing. Where there is an inconsistency between specific exemptions and a Cultural Heritage Management Plan for the relevant works and activities, Heritage Victoria must be contacted for advice on the appropriate approval pathway.

- Specific exemptions do not constitute approvals, authorisations or exemptions under any other legislation, Local Government, State Government or Commonwealth Government requirements, including but not limited to the Planning and Environment Act 1987, the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006, and the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth). Nothing in this declaration exempts owners or their agents from the responsibility to obtain relevant planning, building or environmental approvals from the responsible authority where applicable.

- Care should be taken when working with heritage buildings and objects, as historic fabric may contain dangerous and poisonous materials (for example lead paint and asbestos). Appropriate personal protective equipment should be worn at all times. If you are unsure, seek advice from a qualified heritage architect, heritage consultant or local Council heritage advisor.

- The presence of unsafe materials (for example asbestos, lead paint etc) at a registered place or object does not automatically exempt remedial works or activities in accordance with this category. Approvals under Part 5 of the Act must be obtained to undertake works or activities that are not expressly exempted by the below specific exemptions.

- All works should be informed by a Conservation Management Plan prepared for the place or object. The Executive Director is not bound by any Conservation Management Plan and permits still must be obtained for works suggested in any Conservation Management Plan.

Conditions

- All works or activities permitted under specific exemptions must be planned and carried out in a manner which prevents harm to the registered place or object. Harm includes moving, removing or damaging any part of the registered place or object that contributes to its cultural heritage significance.

- If during the carrying out of works or activities in accordance with specific exemptions original or previously hidden or inaccessible details of the registered place are revealed relating to its cultural heritage significance, including but not limited to historical archaeological remains, such as features, deposits or artefacts, then works must cease and Heritage Victoria notified as soon as possible.

- If during the carrying out of works or activities in accordance with specific exemptions any Aboriginal cultural heritage is discovered or exposed at any time, all works must cease and the Secretary (as defined in the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006) must be contacted immediately to ascertain requirements under the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006.

- If during the carrying out of works or activities in accordance with specific exemptions any munitions or other potentially explosive artefacts are discovered, Victoria Police is to be immediately alerted and the site is to be immediately cleared of all personnel.

- If during the carrying out of works or activities in accordance with specific exemptions any suspected human remains are found the works or activities must cease. The remains must be left in place and protected from harm or damage. Victoria Police and the State Coroner’s Office must be notified immediately. If there are reasonable grounds to believe that the remains are Aboriginal, the State Emergency Control Centre must be immediately notified on 1300 888 544, and, as required under s.17(3)(b) of the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006, all details about the location and nature of the human remains must be provided to the Secretary (as defined in the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006).

Exempt works and activities

Exterior

1. Installation of grab bars, ramps, non-slip surfaces and the like to improve accessibility.

2. Works to replace and install air conditioning and heating appliances and upgrade of electrical and other services.

3. Installation of external lighting, CCTV, alarms and the like.

4. All gardening and landscaping works, including tree removal.

5. All works to structures in the rear yards, including installation and removal of sheds, cubbyhouses and the like.

6. All works to rear fences, including removal and replacement.

7. All other external works that do not change the visual appearance of the building when viewed from Kay Street and surrounding laneways.

Interior8. All updates to kitchens, bathrooms, toilets and laundries including complete refurbishment and replacement.

9. All works to improve thermal comfort (including installation of air conditioning, heating appliances and infrastructure) and upgrade of electrical and other services.

10. All other non-structural internal works that do not permanently alter exposed brickwork or permanently obscure skylights, windows or voids.KAY STREET INFILL HOUSING - Permit Exemption Policy

- The place’s cultural heritage significance relates to its ongoing use as social housing. This ongoing use is supported. It is recognised that a degree of change may be necessary to maintain this use, particularly to the interior.

- Much of the place’s cultural heritage significance relates to its external appearance. Internally, significant characteristics are the room layout, ample natural light and exposed brickwork. If these characteristics can be retained, there is capacity for non-structural change to the interior.

-

-

-

-

-

LOTHIAN BUILDINGS

Victorian Heritage Register H0372

Victorian Heritage Register H0372 -

SHOPS AND RESIDENCES

Victorian Heritage Register H0043

Victorian Heritage Register H0043 -

POLICE STATION

Victorian Heritage Register H1543

Victorian Heritage Register H1543

-

1 Henry Street

Yarra City

Yarra City -

1 Rogers Street

Yarra City

Yarra City

-

-