POINT NEPEAN DEFENCE AND QUARANTINE PRECINCT

3875 POINT NEPEAN ROAD AND 3880 POINT NEPEAN ROAD AND 1-7 FRANKLANDS DRIVE PORTSEA, MORNINGTON PENINSULA SHIRE

-

Add to tour

You must log in to do that.

-

Share

-

Shortlist place

You must log in to do that.

- Download report

Statement of Significance

What is significant?

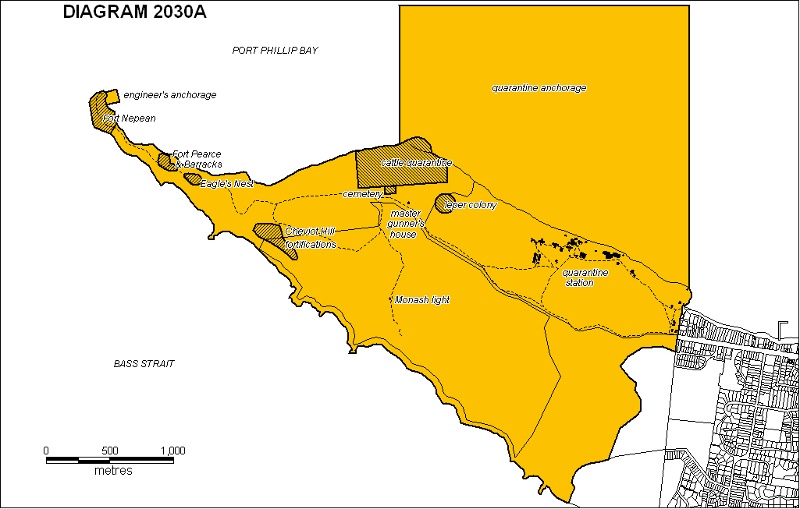

Point Nepean Defence and Quarantine Precinct at the western extremity of the Mornington Peninsula consists of approximately 526 hectares of land about 95 km from Melbourne. The site has an entry from Point Nepean Road, and is partially bounded on the east by the Portsea Golf Club. At the time of Federation, Point Nepean was transferred to Commonwealth ownership, although not gazetted until 1919. In 1988, as part of Australia's Bicentennial celebrations, 300 hectares were transferred to the State of Victoria to become part of a new Point Nepean National Park. This park incorporated the previous Cape Schanck Coastal Park and areas of the Nepean State Park. From August 1995 the park became known as the Mornington Peninsula National Park. A large section of land, some 220ha, south of Defence Road, remains in Commonwealth ownership with no public access due to unexploded ordnance.The Quarantine Station and Police Point have also been in Commonwealth ownership.

A number of Aboriginal sites have been identified on Point Nepean. These include coastal shell middens which reflect indigenous food gathering practices over the past 6000 years.

The first European use of the land was for grazing and lime burning. From the 1840s, limeburning became the chief industry in the Portsea area, supplying lime to Melbourne's building trade. Nepean limestone was shipped to Melbourne from the late 1830s. Many of the early lime kilns at Portsea were located along the shoreline. By 1845, a regular fleet of 20 to 25 schooners carried lime to Melbourne. Large quantities of local timber were cut to supply the lime kilns, causing the natural vegetation of banksia and sheoak to become scarce. Two lime kilns are known to remain on the site.

The limestone Shepherd?s Hut (c.1845-54) is believed to be a rare example of employee housing from this period. Although all the fabric is not original, this may well be of high significance and requires further investigation. It is possible that only the cellar dates from 1845. The hut was used as a dairy from the 1880s until 1897, and as a dispensary until 1908. It became the Regimental Sergeant Major's Office during the Army occupation of the site.

Point Nepean contains the oldest surviving buildings erected for quarantine purposes in Australia. The peninsula was chosen as the first permanent quarantine station in Victoria because of its early isolation, access to shipping, deep-water anchorage and security. The Quarantine Station was constructed from 1852 and operated from the 1850s until 1979. Point Nepean was also used in the management of infectious diseases within Victoria, housing a leper colony from 1885 to the 1930s, when the surviving patients were transferred to Coode Island, and a consumptives' colony from the 1880s. Although the buildings of the leper colony were burnt down in the 1930s, at least one grave of a Chinese leper patient is in the Point Nepean cemetery.

The Point Nepean site housed a remarkable medical complex for its time. The development of the quarantine station reflected changes in medical knowledge about infection and the transmission of disease over the years of its existence and the way major public health issues were dealt with in Victoria. The arrangements of the hospital buildings mirrored the class distinctions of the ships bringing passengers to Melbourne, separating upper class passengers from the rest. The Quarantine Station buildings include: Boatman's Quarters (1888) & Original Entry Road Alignment, Staff Quarters, Hospitals 2-5 (1858-59), Hospital No. 1 (1917), Kitchen No.2 (1858-59), Kitchen No. 3 (c. 1869) Kitchen No.5(c.1885) , First Class Dining Room (1916) Administration Building (1916), Disinfecting & Bathing Complex (1900), Isolation Hospital (1916-20) , Cemetery (1852-54) Cemetery (1854-90) , Crematorium (1892), Heaton's Memorial (1856-58), Isolation Hospital (1916-20), Matron?s Quarters (1856-58), Morgue and Mortuary (1921) , Doctor's Consulting Room and Post Office (1913) relocated in 1925 and used as a Maternity Hospital, Administrative Building and Visiting Staff Quarters (1916-17)and Influenza Huts (1919). The Influenza Huts housed soldiers with influenza returning from World War I when almost 300 ships with over 11,800 passengers were quarantined between November 1918 and August 1919. Other uses of the Quarantine Station have included the temporary housing of several hundred children from the Industrial School at Prince's Bridge in 1867.

The security of the Quarantine Station was crucial to its function. Police guarded a forty foot stretch of land between two fences to keep passengers in and others out of the station. A prefabricated iron police house was replaced in 1859 by a barracks to house a number of police sent from other stations to guard the site whenever passengers were in residence. The single storey timber Superintendent's quarters were built on the site of this barracks in 1916. Police were then accommodated in the new administrative complex. There is some evidence that this 1916 house may contain part of the 1859 police barracks including a simple symmetrical two roomed cottage with a hipped roof, similar to the plan of two-roomed hipped-roof police barracks built by the Public Works Department in several locations in 1859. The police barracks site is also of archaeological significance. A number of wells and possible cess pits are visible in that area.

The Quarantine school (Portsea No. 2929) was located near the east boundary of the site. The remains have not so far been located. The school opened in 1889 with about 23 pupils and appears to have closed in 1894. The site, inside the fences of the Quarantine Station, caused difficulties when there were patients in quarantine. Some of the children subsequently attended Sorrento School No. 1090.

The Quarantine Station jetty, built in timber in 1859-60, was demolished in 1973. The cattle jetty was built in 1878. The anchorage around the Quarantine Station and also that around the Fort Nepean jetty are of archaeological significance.

The other staff residences on the site reflect the quarantine and defence functions. These include the 1899 Medical Superintendent's house, its size and siting appropriate to his position. The house retains its stable, which has been converted to other uses. The 1899 house may include elements of the first doctor's house constructed in 1854. The Matron's House was formerly Pike's Cottage, one of three original stone labourer's cottages built in 1856-58. The Gatekeeper's House was formerly the Boatman's Cottage built in 1888. Residences from the early twentieth century relate mainly to the public health usage of the site such as the four attendants' cottages of c. 1922 near the entrance gate. Their location was well away from the hospital buildings, perhaps to protect families from infection. Buildings dating from the period of Army occupation such as the Cadet Accommodation blocks may not be individually significant but as a collection illustrate this period of development of the site.

A small quarantine cemetery located near the water's edge was used for the burial of passengers from the 'Ticonderoga' and other early ships between 1852 and 1854. The Heaton Monument, a 12-foot high Neo-Egyptian sandstone monument built in 1856-58 still remains at this site.

A new cemetery was established in September 1854, just outside the Station's western boundary and is now located within the Mornington Peninsula National Park. Many early settlers were buried in the new cemetery, as well as sailors from the ships 'Tornado (1868) and 'Cheviot' (1887), wrecked at the Heads. This cemetery was used by local residents until the General Cemetery at Sorrento was opened to the public in 1890. In 1952 the surface remains (several stone monuments and the remains from the Heaton Monument vault), in the old cemetery were relocated to the new cemetery.

The crematorium was built of brick on high ground south of the Quarantine Station complex. Built in 1892, it is said to have been primarily intended for the cremation of people who died of leprosy and is strongly associated with the Quarantine Station operation.

In 1951 the Officer Cadet School of the Australian Army took over the main buildings on the quarantine station site. Very small numbers of people were quarantined from that time until the official closure of the Quarantine Station in 1980. A number of new buildings were constructed c.1963-65 as part of the Officer Cadet School such as a gymnasium, barracks, library and gatehouse. In 1984 the Officer Cadet School was relocated to Canberra. The main Parade Ground and Flagstaff have an historical association with the Officer Cadet School.

The School of Army Health replaced the Officer Cadet School from 1985 to 1998. This was the main establishment in Australia for the training of Army health officers. In 1999 the Quarantine Station buildings were used to accommodate Kosovar refugees.

Point Nepean was a major part of the Victorian coastal defence system which made Port Phillip Bay reputedly the most heavily defended harbour of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century in the southern hemisphere. It is said that the fortifications at Point Nepean are the best examples demonstrating the development of military technology of the Port Phillip Bay network. Remaining buildings and structures from the defence use of the site include the gun emplacements, light emplacements, observation posts, tunnels, Pearce Barracks, Fort Pearce, Eagle's Nest, and the Engine House, and a number of archaeological sites such as Happy Valley, the site of a World War II camp. The land south of Defence Road was used by the Army as an operational training ground. Rifle, mortar, anti-tank and machine gun firing ranges were constructed in this area. The Lewis Basin was used for field training exercises, as evidenced by the obstacle course facility built in this area. The Monash Light navigational aid is located in this area, with a cleared tree/fire break maintaining an uninterrupted line of vision between the Light and the navigational beacon located at the western end of Ticonderoga Bay. This area has had limited disturbance over the past hundred years because it has been used only for defence activities. The area contained observation points associated with the fortifications, observation points for range firing at sea targets and range points for such firing.

The coastline of Point Nepean, on one side of the hazardous entrance to Port Phillip Bay, has been the site of many wrecks, as ships passed through the Heads to and from the port of Melbourne. The causes of the wrecks have included collisions, weather conditions, ignorance of the hazards of the Rip, negligence, drunkenness, navigational errors and arson. In December 1967 the Australian Prime Minister Harold Holt disappeared and was believed to have drowned while swimming in the surf at Cheviot Beach.

There has been a long association between the community and the defence occupation of the site, in particular, involvement with the activities of the Officer Cadet School and School of Army Health. The community holds strong shared memories of experiences and social life on that land, which have created a strong connection to the place. The ovals north of Defence Road and west of the Quarantine Station were used for joint defence-community and local sporting activities. The areas of community activity were not restricted to the buildings but included privileged access to various parts of the whole of Point Nepean.

After determining in 1998 that the Point Nepean land was surplus to Australian Defence Force requirements, Commonwealth Government offers to return large sections of the land to the Victorian people were rejected several times by the Victorian Government.

The Commonwealth's insistence in 2001 that the Victorian Government pay the cost of clearing unexploded ordnance from the land on offer led to a protracted political dispute between the two governments.

In April 2002 the Commonwealth announced its intention to dispose of its land at Point Nepean after a community consultation process to evaluate future usages. During this process in late 2002 and early 2003, a series of public protests demonstrated widespread community support for a campaign to 'Save Point Nepean' by keeping the land in public ownership. In March 2003 the Commonwealth Government agreed to give 205 hectares of native bushland to the Victorian Government for a national park, with the Commonwealth paying for the clearance of unexploded ordnance, and 17 hectares of land at Police Point to the Mornington Peninsula Shire Council for use as public open space.

The remaining 90 hectares of Commonwealth land were offered to the Victorian Government as a priority sale at market value. When the Victorian Government rejected these terms, the Commonwealth invited tenders for a 40-year lease. During the tender period, the National Trust and the Victorian National Parks Association led a vigorous protest campaign against the proposed lease. After announcing a preferred tenderer in October 2003, the Commonwealth said in December 2003 that it had terminated the lease process after failing to reach a 'satisfactory outcome'. At the same time, the Commonwealth declared that the remaining 90 hectares would be vested in a charitable trust called the Point Nepean Community Trust with the intention of transferring the land to the Victorian Government for integration into a national park within five years.

How is it significant?

Point Nepean Defence and Quarantine Precinct is of archaeological, aesthetic, architectural, historical, scientific and social significance to the State of Victoria.

Why is it significant?

Point Nepean Defence and Quarantine Precinct is of outstanding aesthetic significance for its landscape, its open space, some avenues and stands of trees, and its internal and external views. These views include the relationship between bush and sea, between the buildings and their context, the views across the Heads to Queenscliff and the Otways, views back towards Melbourne, to the Bay and from the water to the site, and the 360 degree views from the narrowest portion of land near the tip of the peninsula.

Point Nepean Defence and Quarantine Precinct is of architectural significance for the limestone Shepherd's Hut [c.1845-54] believed to be a rare example of employee housing from this period.

Point Nepean Defence and Quarantine Precinct is of architectural significance for its quarantine station buildings, a rare example of a building type and the only example in Victoria. The hospital buildings of 1858-59 are important examples of Early Colonial buildings, which are rare in Victoria, and the work of the Public Works Department architect, Alfred Scurry. The design of the Administration building is an accomplished example of Colonial Revival architecture, with planning influences from noted architect, J S Murdoch. The y-shaped Isolation Hospital (1916-20) is a rare example of a building type with an exchange room for staff to change their clothes between wards. The other residential

buildings of the later period of construction are of architectural significance as representative examples of twentieth century government employee housing

Point Nepean Defence and Quarantine Precinct is of outstanding historical significance for its capacity to demonstrate the historic use of the site over a long period, from the Aboriginal period to the most recent use of the land for recreation. Each phase of use has left evidence in the landscape, in built form, or in archaeological remains. The shell middens demonstrate the use of the place by indigenous people. The limestone Shepherd's Hut (c.1845-1854) reflects the early grazing use by Europeans and the remaining lime kilns, the limeburning industry. Significant historical archaeological sites are likely to exist across the whole of Point Nepean, from pre-quarantine use of the land right through to the defence operations.

The Point Nepean site, including the Quarantine Station and the two cemetery sites and crematorium, is of historical significance in the history of migration and the history of public health in Victoria. The Station is historically significant as the first permanent quarantine station in Victoria and one of the earliest and most substantial in Australia. It contains the oldest surviving buildings erected for quarantine purposes in Australia.

Point Nepean Defence and Quarantine Precinct is historically significant in the history of defence in Victoria from its first use as one of a number of colonial defence installations round Port Phillip Bay, as an important Commonwealth defence site before and during the two World Wars and in the latter twentieth century, the site used for the training of Australian Army personnel at the Officer Cadet school and the School of Army Health.

The staff residences of all periods of construction are of historical significance in reflecting the quarantine and defence functions. Buildings dating from the period of Army occupation may not be individually significant but as a collection illustrate this period of development of the site.

Point Nepean Defence and Quarantine Precinct is historically significant as the site of many shipwrecks in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, demonstrating the importance of maritime activity to the development of Victoria.

Point Nepean Defence and Quarantine Precinct is historically significant as the place where Australian Prime Minister Harold Holt is believed to have drowned.

Point Nepean Defence and Quarantine Precinct is an area of high archaeological significance as the location of early European settlement in Victoria, which included agricultural and limeburning activities. Significant historical archaeological sites exist across the whole of Point Nepean, from pre-quarantine use of the land right through to the defence operations. Archaeological remains on the police residence site are particularly important. The defence exercise area south of Defence Road and Happy Valley are also of archaeological significance.

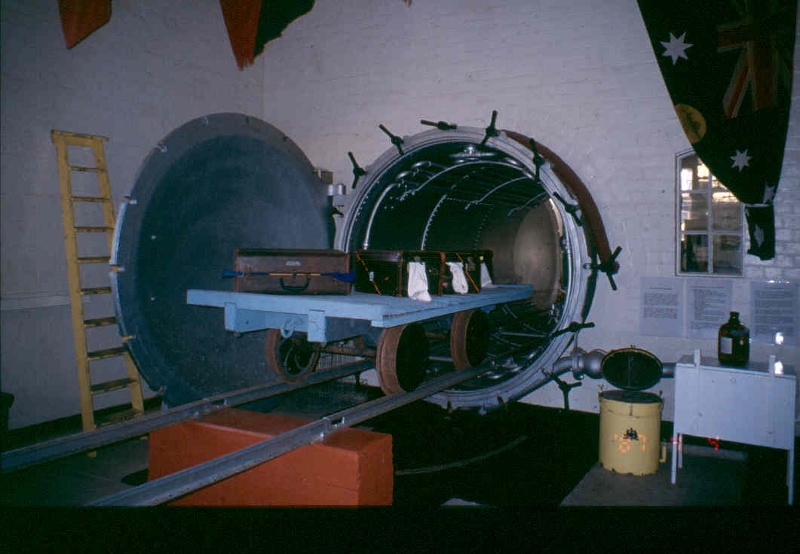

The Disinfecting and Bathing Complex at the Quarantine Station is of scientific significance as a rare representative of its type which became the model for a series of similar complexes around Australia. The complex retains equipment and fabric which can demonstrate the history of the control and management of infectious diseases in Australia.

Point Nepean Defence and Quarantine Precinct is of social significance for its recreational use since at least the 1950s when defence authorities allowed community use and joint defence-community sporting activities. The part of Point Nepean which has been a national park since 1988 is of social significance as a tourist attraction in allowing public access to a unique site of natural and historic value within Victoria

The Precinct is also of social significance because of the sustained and effective broad based community action involved in having the entire site set aside as public land rather than being sold to private interests which was the Federal Government?s original plan.

-

-

POINT NEPEAN DEFENCE AND QUARANTINE PRECINCT - History

The former Portsea Quarantine Station has cultural significance for its associations with European Settlement in the Point Nepean area. Point Nepean not only has natural and Aboriginal significance, but has major historical significance because of its individual sites, which combine to form a complex overlay of the history of the area. It is an area of potential archaeological significance as the location of early European settlement in Victoria, which included pastoral minor agriculture and limeburning activities. The Peninsula has considerable significance as the location of early quarantine and later defence activities, both of which were important in the colonial and Commonwealth periods.

Point Nepean contains the site of the oldest surviving buildings erected for quarantine purposes in Australia. The peninsula was chosen as the first permanent quarantine station in Victoria because of its early isolation, access to shipping, deep-water anchorage and security.

Point Nepean was also important as ‘ a major and integral link in the Victorian coastal defence system which contributed to making Port Phillip Bay reputedly the most heavily defended harbour of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century in the southern hemisphere. It is said that the fortifications at Point Nepean are ‘ the best examples of the development of military technology of the Port Phillip Bay network.

The quarantine and defence establishments on the Nepean Peninsula developed independently, but at least from the 1950s they have shared a common history.

GRAZINGThe area occupied by the former Quarantine Station at Portsea on the Nepean Peninsula was permanently settled by Europeans in the 1830s and 1840s. The earliest settlers were pioneers engaged in sealing, grazing, limeburning and fishing. The grazing and limeburning activities have particular significance for the early history of the Quarantine Station site.

The earliest permanent settler in the 1830s was an overlander, Edward Hobson, who arrived from Parramatta in 1837 and took out a grazing licence for the area from Boneo to Point Nepean. Hobson then leased the Tootgarook run between Dromana and Rye, which he occupied from 1838 to 1850. There is no physical evidence of Hobson’s grazing activities on the Quarantine Station site.

Another pioneer settler, Bunting Johnstone leased a run (known as the Bunting Johnstone run) at Point Nepean in 1843. This was transferred in 1844 to James Sandle Ford, who settled permanently in Portsea. Ford developed his land, reared cattle and bred horses, as well as grazing stock. He planted crops and built his own lime kiln. His grazing paddock, house, hut, stockyard and kiln were located in the vicinity of Portsea Back Beach Road and Franklin Road, outside the Quarantine Station.

LIMEBURNING

From the 1840s, limeburning became the chief industry in the Portsea area, supplying limestone and lime to Melbourne’s building trade. Nepean limestone, which was said to be excellent, was shipped to Melbourne from the late 1830s. Many of the early lime kilns at Portsea were located along the shoreline (including the shoreline of the future Quarantine Station), when lime deposits were discovered nearby. By 1845, a regular fleet of 20 to 25 limecraft (schooners of 30 to 40 tons) carried lime from the Nepean Peninsula to Melbourne.

Large quantities of the local timber were cut to supply the lime kilns, causing the natural vegetation of banksia and sheoaks in the Portsea area to become scarce. By 1853, timber was so scarce that the colonial government ruled that timber cutting was prohibited within 1 mile of the coast in the District of Western Port, which includes the Nepean Peninsula.

By the early 1850s, there were six licence holders operating in the Portsea area, some within the boundaries of the future Quarantine Station. According to a report from Surveyor-General R. Hoddle to Lieut. Governor La Trobe on 27 October 1852, they were Daniel Sullivan, Robert White, John Divine, James Ford and H.G. Cameron. Ford was the Point Nepean settler mentioned above. Daniel Sullivan was a pastoral pioneer who held a Point Nepean grazing licence from 1840 to 1849, which was then held by his son Patrick from 1850 to 1851. This licence was cancelled when the Quarantine Station was established on the site.

The 1852 District Surveyor’s sketch, figure 3, which had additional notes, showed the kilns and other buildings of the Portsea limeburners. It gives a good indication of the location of these structures in relation to the future Quarantine Station. Sullivan’s kiln, house and garden area were shown on the coast near Police Point, while ‘William Cannon’s lime kiln’ was marked near the western boundary of the Quarantine Station.

The main Quarantine Station facilities were centred around the Sullivan property. However, all that remains today from the combined limeburning and grazing history of the Station area are lime kiln ruins at Police Point and north of Hospital Building 1, and, possibly, the Shepherd’s Hut. (Building No. 7).

THE SHEPHERD’S HUT

This is said to be the earliest surviving building on the Quarantine Station site and to date from 1845-1854. A single-room stone building with a stone basement, the building has a poorly documented history and the date and function of the building has not been substantiated. Sullivan’s Cottage (now gone) and the Shepherd’s Hut are shown as two separate buildings on Power’s conjectural site plan of the Quarantine Station c1856. The Shepherd’s Hut is shown on Power’s 1875 site plan. Power does not provide sources for these plans. Sullivan’s Cottage was located on the site of the present Parade Ground, and was shown on the 1875 plan as ‘work shops’. Archaeological investigation may uncover remains of Sullivan’s Cottage. To date there is no positive evidence to link the Shepard’s Hut with the early grazing and limeburning history of the area, though the property is listed by the National Trust and the Australian Heritage Commission.

MARITIME QUARANTINE STATIONS IN THE AUSTRALIAN COLONIESTHE EARLY YEARS OF EUROPEAN SETTLEMENT

From the time that the first European settlers came to Australia there were fears expressed by colonial governments concerning the possible spread of ship born diseases from Great Britain and Europe. Colonial governments were anxious to ‘protect the perceived pristine health of the new colony from the endemic diseases of other continents’. It was thought that the best protection was the establishment of quarantine stations in coastal areas, where migrating passengers and ships’ crews on all arriving vessels could be held for a time until the threat of passing on diseases had passed. Maritime quarantine has been defined, as ‘the enforced detention and segregation of vessels arriving in a port, together with all persons and things on board, believed to be infected with the poison of certain epidemic diseases, for specified periods’. It was a policy based on accepted theories, popular in the 19th century, about the handling of infectious diseases.

NEW SOUTH WALES’ NORTH HEAD QUARANTINE STATION

During the early 1830s, a cholera epidemic which began in Europe in 1830 had reached Britain in 1832. Colonial NSW expressed its fears by passing the first Australian Quarantine Act. There had already been fears in the colony concerning stories of ‘infected convict ships being sent to Australia’. In 1834, under the new Act, a first Quarantine Ground and Station was proclaimed at Spring Cove, North Head in New South Wales. All vessels from the United Kingdom were to be held there and subjected to quarantine restrictions. This first NSW Quarantine Act also applied to colonial Victoria, which was then a dependency of the mother colony. The NSW Quarantine Station remains but was closed in 1984.

VICTORIA’S FIRST QUARANTINE GROUND

Colonial Victoria’s first quarantine ground was at Point Ormond, known earlier as ‘Red Bluff’. This followed the arrival in April 1840 of the barque ‘Glen Huntly’ in Hobson’s Bay with 157 Government immigrants, many of whom were suffering from typhus fever. Healthy passengers were released from the quarantine station on 13 and 20 June. Those who died were buried at Red Bluff but, in 1898, were removed to the St. Kilda Cemetery.

THE PORTSEA QUARANTINE STATIONThe Point Nepean Quarantine Station was the first permanent quarantine station in Victoria and one of the earliest and most substantial in Australia. It contains the oldest surviving buildings erected for quarantine purposes in Australia.

THE SITE

After the discovery of gold in Victoria and the resulting huge increase in migration to the colony, the Point Ormond site became increasingly unsuitable for its quarantine function. Detention was difficult to enforce and the site was clearly too close to settled areas. Therefore, ‘with the increased shipping after the gold discoveries and the associated overcrowding and unsanitary conditions on board many ships, steps were taken to find and occupy a new site’.

When the Point Ormond Quarantine Station was finally abandoned, Point Nepean was suggested as an ideal alternate site. It was in an isolated position, which made it an excellent location for a quarantine station. There was good anchorage and easy access ‘both from inside the Heads… and from Shortlands Bluff’. Point Nepean was a healthy place with soil ‘at all times dry’ and ‘the air pure’. Water could be easily obtained by sinking wells, and the water obtained was abundant and of ‘sufficient purity’. Moreover, a root known as pennyroyal, which grew wild in the area, was said to ‘cure scurvy in a short time’. Scurvy was a great scourge to sea-going travellers in the 19th century.

After the Point Nepean site was selected in October 1852, steps were taken to terminate the occupiers’ licences and plan the site’s future development. In early 1852, the Victorian government (which had separated from NSW in 1851) allowed £5,000 towards the erection of a sanatorium. The holders of limeburning licences, then occupying the chosen site, were given one month’s notice to quit the area.

The boundaries of the new station were marked out, rapidly approved by La Trobe on 22 November 1852 (after the scare caused by the arrival of the ‘Ticonderoga’), and gazetted on 23 November 1852. The limeburning licences were cancelled in December 1853 although settlers continued to occupy the western end of the site. Eventually, on 31 March 1871, it was announced in the Victorian Government Gazette that the Quarantine Station of 1,400 acres (547 hectares) would be permanently reserved for sanatorium purposes. The order for the permanent reservation, dated 21 June 1871, formally incorporated a strip of land along the eastern boundary of the site, the site of the original police barracks at the Station.

Later, in 1877, the Quarantine Station Reserve was reduced to 987 acres (356 hectares) with the Defence Reserve (170 hectares) located on its western side. The Quarantine Station land was transferred from the State to the Commonwealth Government on 1 July 1909, after Federation, although not gazetted until 1919. Some 50 years later, in 1954, an area of the Quarantine land was transferred to the Army. The Quarantine Station ceased operations on 1 October 1978 and was formally closed on 2 April 1980.

From 1954 the Army held 453 hectares, leaving just 83 hectares for use by the Department of Health. The Officer Cadet School occupied the property until 1984. From 1985 to 1998 the property housed the School of Army Health.

THE EARLIEST BUILDINGS AT THE QUARANTINE STATION

The arrival of the ‘Ticonderoga’ at the Heads on 3 November 1852 with nearly 300 ill people aboard, and 100 deaths from ‘fever’ during the voyage, was the event, which hastened the opening of the new Quarantine Station at Point Nepean. Reports were immediately sent to Governor La Trobe, telling of the conditions on board the ship and the steps taken by local authorities to deal with the emergency.

Captain Ferguson, the Harbour Master reported that about 40 of the able bodied people had been housed in temporary tents. Both Sullivan and, later, Cannon (another limeburner) ‘were removed to other parts of the Peninsula’. A vessel, the ‘Lysander’, fitted out as a hospital ship was sent from Melbourne on 6 November 1852.

Stonemasons among the immigrants were employed to construct a stone house near the Sullivans’ Cottage. The Colonial Architect was asked to send a ‘plain plan or sketch of a large airy barracks or depot,’ and Captain Ferguson procured food supplies for the establishment.

No physical evidence remains of the houses and other structures used in these first years in the development of the Quarantine Station, except, possibly the Shepherd’s Hut discussed in Section 2.2.3.

THE LAYOUT OF THE QUARANTINE STATION COMPLEX

The Portsea Quarantine Station is notable for the layout of the complex, which retains evidence of its occupation from the mid 1850s. The period in which these first permanent Quarantine buildings were constructed is one of the most significant phases in the complex’s history.

The complex comprises five distinct precincts:

(1)The disinfecting precinct was always located on the flat close to the jetty (now gone), and was the first point of contact with the Station for incoming passengers. Bathing and laundry facilities, administration and public offices, doctor’s consulting room and stores were placed in this precinct.

(2)The five accommodation wards, or hospitals, were well spaced along the foreshore, this siting determining the broad layout of the station. Their regular placement and uniform design provided ‘a sense of cohesion and unity to the layout which is not found in many other stations in Australia’.

(3)The doctor’s residence was located on the rise behind Hospital No. 1. ‘allowing both segregation from and ease of supervision of the station’. Hospital No. 5 was later used for the sick passengers. This was a major change in functional relationships for the station.

(4)The isolation hospital was placed at one end of the building compound, initially at the eastern end and later, the western end.

(5)Staff quarters were always sited away from the main compound. Originally, they were dispersed around the perimeters of the building compound but later were concentrated further away inside the eastern boundary and entrance gate. Although the Army (which gradually occupied the complex in the 1950s) erected several buildings on the site, particularly around Hospitals 1 and 2 (Buildings 1 and 4), the functional layout of the station has remained essentially intact. Power’s study of the former Quarantine Station includes a sketch, which shows the functional layout of the complex.

BUILDINGS CONSTRUCTED PRE-1856

The first permanent buildings constructed on the site prior to 1856 included a timber hospital building designed by the Colonial Architect. This structure was 65 feet by 20 feet, divided into two equal compartments, and was roofed with zinc, later replaced with galvanized iron. This building was replaced as a hospital in 1859 and became a clothing and bedding store until c1875. It was probably demolished c1919. There was also a two-roomed Medical Officer’s quarters, which was replaced by a two-storey building in c1880, and replaced again in 1899 by a single-storey timber residence. Power suggests that the original two-roomed building may still survive.

Between late 1854 and early 1855, a new stone store was built close to the foreshore near the pier. This building was 60 feet by 20 feet and had a zinc roof. It was demolished c1910. There was also a building known as ‘Dr Williams old hut’ near the eastern boundary; a police barracks just outside the boundary fence; and a two-roomed prefabricated iron house occupied by the police. Tents continued to be used as back-up accommodation.

Archival information

Power provided considerable information about the development of the Quarantine Station after his examination of a great deal of primary source material, including building contracts and architectural drawings held in the National Archives and at the Public Records Office of Victoria. Power includes conjectural site plans of how the Quarantine Station might have looked in c1856, 1875,1895, 1927 and 1984. However he does not provide specific references for each plan.A further series of site plans of the Quarantine Station dating from 1901, 1916, 1920, 1950-1961 have been located recently in the National Archives, after consulting Patrick Miller’s Bibliography. These include a 1920 plan (See Figure 13) prepared by the Commonwealth Department of Works and Railways, Vic./Tas. Branch, which lists all the buildings and other structures on the site at that time. This can be compared with 1950s (See Figure 16) plans of Engineering Services at the Quarantine Station, prepared by the Commonwealth Department of Works and Housing, Vic./Tas. Branch, which confirmed the unchanged layout of the complex during the Army’s occupation.

THE CEMETERY

A small cemetery was established for the ‘Ticonderoga’ victims near the main Station complex. It measured 175 feet by 115 feet and was located near the water’s edge. It is shown on figure 13. The Heaton Monument, a 12-foot high Neo-Egyptian sandstone monument with a single vault below still remains. This monument was built in 1856-58 during the construction of the five accommodation (hospital) blocks at the direction of George Heaton, who emigrated to Victoria, where he worked first as a limeburner at Rye. From 1856-1859, Heaton was employed as a supervisor when the first permanent stone buildings were erected at the Quarantine Station. He was not buried in the old cemetery, however, but, after moving from the area, was buried in the Old Melbourne Cemetery.

The beachfront cemetery was only used in the period 1852-54. A new cemetery was established in September 1854, just outside the Station’s western boundary. The remains of the people buried in the original cemetery were not removed and are still interred there. They number about 100, and include passengers from the ‘Ticonderoga’ (about 70) and passengers from other early ships.

Many early settlers were buried in the new cemetery, including James Sandle Ford and Edward Skelton, as well as sailors from the ships ‘Tornado’ (1868) and ‘Cheviot’ (1887), wrecked at the Heads. At least one Chinese suffering from leprosy, who died at the Quarantine Station, was buried in the new cemetery. This cemetery was used by local residents until the General Cemetery at Sorrento was opened to the public in 1890.

In 1952 the surface remains (several stone monuments and the remains at the Heaton Monument vault), in the old cemetery were relocated to the new cemetery. Both the original cemetery and the later Point Nepean Cemetery (the latter now outside the Norris Barracks grounds) are of historical significance for their association with the early history of the Quarantine Station. The later cemetery is located within the Mornington Peninsula National Park and is under the management of Parks Victoria. It is neatly fenced and well cared for. The Friends of the Quarantine Museum would like the original cemetery to be re-established and conserved.

THE SECOND PHASE: 1856-1875

The physical form of the Quarantine Station as it is today is largely a result of the five group of institutional buildings constructed on the site between 1858 and 1859. This group includes five accommodation wards or hospitals, two-storeyed structures built of local stone, which have been described as probably the oldest institutional complex in the state. Powell claims that during this period ‘structures were erected with some thought to long-term planning’ rather than just ad hoc responses to an emergency. They were designed in colonial barracks style, similar to the General Hospital blocks in Maquarie Street, Sydney, constructed 1810-15.

The five stone hospitals

These structures still provide the dominant physical form of the Quarantine Station. One was built for sick patients and the other four for healthy passengers. Four are still intact, but Hospital No. 1 was burned down in 1916 and replaced in c1919. Some hospitals still have their original associated stone kitchens.Alfred Scurry, Clerk of Works for the Geelong Office of the Public Works Department, designed the 1850s buildings. Constructed of rough-cast stone, quarried on the site, each building contained four wards, designed to accommodate 25 people. The Station’s total capacity was 500. Hospital No. 1, located on the rise, was to accommodate the sick.

As O’Neill has pointed out, the arrangements in the five buildings ‘mirrored the class distinctions of the ships, which brought the passengers to Melbourne’. The division of each building into wards certainly allowed for some segregation of classes, sexes and diseases. The 1872 Royal Commission was told that,

… ‘The last hospital on the hill is the one devoted to the medical treatment of contagious disease, and the rest of the passengers may be landed out of the ship, placed in the buildings on the flat, and classified, second, third, steerage and saloon – those landed are kept distinct… and the passengers, as it sometimes happens… the second-class passengers, with the sailors, were drafted off some fortnight or more before the third-cabin passengers.’

The stone kitchens

A three-roomed stone kitchen was constructed behind Hospitals No. 1 and 2 (Building No. 4) in 1858 and remained in service until it was demolished c1916. A similar kitchen (Building No. 21) was built behind Hospital No. 4 (Building No. 22) to service the three hospitals on the flat. It was not until 1869, however, that a kitchen (Building No. 15) was built behind Hospital No. 3 (Building No. 16). This was the last of the stone buildings constructed at the Quarantine Station. The stone kitchen associated with Hospital No. 4, therefore, is the only remaining 1858-59 Kitchen on the Station site.The remaining 1858-59 Hospitals Nos. 2, 3, 4 and 5 are known now as Buildings Nos. 4, 16, 22 and 25.

Matron’s Cottage / Pike’s Cottage

Three stone cottages for labourers’ permanently employed at the station, one of which remains, were early examples of the staff quarters erected around the periphery of the building compound. Constructed in 1856-1858, each had two rooms with later timber extensions and outbuildings. The one that has survived was known as the Matron’s Cottage (Building PMQ. 1035) and was located behind Hospital No. 1. This cottage is probably the second oldest building on the Quarantine Station site. An original drawing design used for all three labourers’ cottages has survived.The Matron’s Cottage was known originally as Pike’s Cottage, named after its first occupant, Edward Pike, who lived there with his wife, Elizabeth, and their family. Pike was a boatman, an important job, and was responsible for bringing medical staff from the Station to a ship, or bringing passengers from a ship to the Station. The former Pike’s Cottage became the Matron’s Cottage in the 1880s. Between 1954 (when the Officer Cadet School commenced at the Quarantine Station site) and 1977, the cottage became the ‘Quarantine Observation Block’ in the Married Quarters area. During the years between 1970 and 1974, when quarantines were brought from Tullamarine Airport to Portsea, most were housed in Pike’s Cottage.

The Jetty

The Quarantine jetty, constructed in 1858-59, was a prominent feature of the Portsea Quarantine Station layout. Modifications were made to the structure in 1866, 1884, 1916 and 1938. It was demolished in 1973. The wharf and jetty, and an associated group of buildings had great functional significance as the place where all landed passengers made their first contact with the quarantine station. The associated structures were the c1911 timber waiting room, the timber clean luggage receiving store (1910 with 1916 extensions), the timber shower block (c1925), the 1916 boiler and additional disinfecting chamber, and the tramway system linking all the components.The Friends of the Quarantine Museum, in recognition of the functional importance of the jetty would like it to be rebuilt using the original 1858-59 drawings. The site of the former jetty has historical and social significance and potential archaeological significance.

Alfred Scurry

Alfred Scurry was employed by the Public Works Department of Victoria as Clerk of Works for the Geelong Office between 1853 and August 1860. He was associated with work on the Geelong Customs House designed in 1855 by the architect E. Davidson; with the five accommodation wards at the Portsea Quarantine Station constructed between 1858 and 1859; and with the Eltham Court House built in 1860. Alfred Scurry and Charles Maplestone were Clerks of Works in 1859 for the Court of Petty Sessions at Digby and additions to the gaol at Geelong. It is thought that Scurry did the drawings for the gaol. In 1860, Scurry ceased working for the PWD and, in November 1863, called tenders for ‘premises for Kingsland in Dudley Street, West Melbourne’.The early disinfecting precinct

In 1864, a contract for a ‘Disinfecting House’ at a cost of £703, was let to Enoch Chambers. This early example of a disinfecting precinct, an increasingly important part of such a complex, was located on the flat near the foreshore. Later, in 1866, a stone bath-house and laundry (Building No. 59) was constructed close to a drying-house. The bath-house consisted of two separate rooms containing 12 baths each. The wash-house section had copper boilers, washing troughs and tubs. A second wash-house, fitted with two copper boilers, was erected close by. An original drawing of the 1866 stone bath and wash-house survives in Commonwealth Archives.These buildings have great heritage value and in 1900 were incorporated into the new Disinfecting and Bathing Complex, a notable component of the Portsea Quarantine Station.

Shane Power’s 1875 site plan of the Quarantine Station, based on an unscaled drawing, probably by the Storekeeper, James Walker, shows the disinfecting precinct near the wharf and jetty. By this time the complex included the five hospitals, the early doctor’s residence, storekeeper’s quarters, labourer’s quarters and the shepherd’s hut (by then used as a paint store). This map shows a road along the southern boundary of the Station and much further south the Military Road (now Defence Road) which led to the Army’s Fort Nepean. This early date for Military Road, which was regraded in 1916, has been questioned by some researchers.

THE THIRD PHASE: 1875-1899

There were minor changes to the basic layout of the Quarantine complex during these years, with some modifications made to individual buildings. Hospital No. 5 (Building No. 25) for example, was converted for use as an Isolation Hospital and a new detached timber kitchen (Building No. 26) was erected behind it in 1885. This 1880s Kitchen remains.

Social life at the Station in the 1880s

After improvement in transport, including the introduction of Bay steamers and promotion by land developers, the Nepean Peninsula ‘began to lose some of its earlier reputation as an isolated exclusive place, which only the wealthy might visit’. The Peninsula was chosen in the 1850s as the site for the Quarantine Station because of the area’s isolation. From the 1880s, the Peninsula’s towns were no longer isolated and became popular holiday resorts. Visitors touring the Peninsula began to take an interest in the defence and quarantine establishments at Portsea, which, over the years, became popular tourist attractions.During the 1880s, attempts were made to improve the social life at the Quarantine Station, particularly for the First Class Passengers. In 1884, Hospitals Nos. 1 and 2 (Buildings 1 and 4) were converted to first and second-class passenger accommodation. The modifications made to Hospital No. 1 included the creation of a large dining room. All passengers at the Station had previously eaten in their bedrooms. Other wards were partitioned into single and double bedrooms. Archival drawings show the large dining room on the ground floor with the other half of the floor divided into single and double rooms. Unfortunately, this building was destroyed by fire in 1916 and replaced in c1919 with a two-storeyed brick building painted to match the earlier stone buildings.

Sketches of the Portsea Quarantine Station in 1882, which appeared in the Australasian Sketcher, showed elegantly dressed family groups (probably First Class Passengers) seated in the Station grounds reading books and newspapers; young couples playing tennis; and others standing by the coast watching passing vessels in the Bay. One sketch, titled ‘communicating with friends at the Portsea Gate,’ showed the frustration of a group of quarantines staring at friends across the two barrier fences, watched over by a vigilant policeman.

During the 1880s, the nearby towns of Portsea and Sorrento had become popular tourist resorts, with regular shiploads of tourists arriving by Bay steamers. One of the fences at the Quarantine Station was to keep the internees inside the Quarantine Station, the other to make sure no outsiders entered the grounds.

The main diseases requiring quarantine at this time were cholera, typhus, diphtheria, smallpox, measles, chickenpox, yellow fever, plague and influenza. But typhus and cholera were less of a threat once public health authorities became more effective in safeguarding urban water supplies and sewering the cities.

By the 1880s, vaccination or confinement in quarantine was the choice faced by passengers and crews travelling from smallpox-infected ports or with an infected person on board. While previously a whole ship’s company had been detained, later, a medical check on vaccinations were all that was required.

FOURTH PHASE: 1899-1925

1899-1909

The first years of the new century marked the second-most important period in the Portsea Quarantine complex’s development. According to Power, ‘The first substantial upgrading of the complex’s facilities occurred in 1899-1900 in response to the impact of overseas developments, outbreaks of plague in Asia and the strong influence of Victoria’s Chief Public Health Official, Dr Astley Gresswell’.Dr Gresswell was one of the most influential people in quarantine administration in Australia during the period of greatest change. An Englishman, Gresswell was an Oxford graduate, who had spent some time travelling and studying public health conditions and administration in Europe. In March 1890, he took up an appointment as Medical Inspector in the newly-created Department of Public Health. It was during the late 1890s and early 1900s, when Gresswell was most active, that the Station at Point Nepean was upgraded. It is said that,

‘Australian Quarantine methods may be said to have taken their origin from the first Australian Sanitary Conference in 1884, but to have begun their full development in practical form in the decade 1890-1900, during which period the influence of such men as Dr Ashburton Thompson and Dr Gresswell began to develop the principles of local quarantine, and to promulgate the ideas of a Federal quarantine system.’

During those years, a new disinfecting and bathing complex was constructed at Portsea by the Victorian Government, which became ‘the focal point in the quarantine process for the remaining life of the Station’. There was also a new 1899 medical superintendent’s quarters, (Building No. PMQ 1038) incorporating part of the former structure.

1891 Contour Maps of Mornington Peninsula

A number of contour maps of the Peninsula prepared specially for the use of the Victorian Defence Department by Alexander Black, Surveyor General, in December 1891, showed a cluster of buildings at the Quarantine Station in the Sanitorium Reserve. The track through the Station , which extended to the Army Barracks at Point Nepean (shown on the 1875 map used by Power), is indicated as following the Telegraph Line Track through Portsea. The jetty at the quarantine station and another at the Cattle Quarantine area are shown and a ‘signal staff’ on the coast near the Leeper (sic) Station. Refer to Figures 4 & 5.

Medical Superintendent’s Quarters

A June 1901 Block Plan of the Quarantine Station at Point Nepean showed the layout of the Station in the vicinity of the new Medical Superintendent’s Quarters and Gatekeeper’s Quarters, with Police Quarters on the east side of the Station’s eastern boundary fence. This 1901 plan included a detailed sketch of the new 1890s residence and also showed the fences, paths and roads that formed an important part of the early Station layout. Some of these early paths and roads remain. There was a picket fence surrounding the residence while paling fences bordered the large ‘flower garden’ and ‘vegetable garden’ at its rear. A post and rail fence was indicated along the bayside coastal boundary to the eastern boundary. There was another picket fence around Hospital No. 1. A line of road (now Coles Track?) led to the old cattle jetty while other roads were marked on either side of the boundary fence at the entrance to the Station. One led to Portsea and the other was a mere ‘scrub track’. The Station buildings were surrounded by ‘scrub.’ The Telegraph line (established in 1874) was also marked as can be seen in Figure 13.Disinfecting and Bathing Complex

This complex, erected in 1899-1900, was quite substantial and was almost certainly the first of its type in Australia. It has great heritage value and served as a model for a series of similar complexes throughout Australia constructed during the Commonwealth Government’s upgrading program in the decade after 1909.The Portsea complex, constructed in the 1899 - 1900 under a single contract, included a red brick boiler house with a disinfecting chamber, two brick bath blocks adjacent, and a timber infected luggage receiving store. These buildings were located near and complemented the existing 1866 stone bath and wash-house. This early bath and wash house, one of the last stone buildings erected on the site, has great heritage value as an example of the earlier bathing and disinfecting process.

1909-1925

The Commonwealth Government took over the control of the Portsea Quarantine Station in 1909. This followed the 1904 Conference of State Medical Officers, which recommended the creation of a Federal Quarantine Service, to be controlled by the Commonwealth Government but officiated by Chief Health Officers in each State. This was adopted by a Conference of Premiers in 1906. A Quarantine Bill was introduced on 16 July 1907, and the service began operations on 1 July 1909 within the Commonwealth Department of Trade and Customs. In 1910, Victoria withdrew from the system and the Commonwealth was urged to appoint its own staff. In August 1911 a Chief Quarantine Officer was appointed for Victoria. The Quarantine Service continued as part of the Department of Trade and Customs until 7 March 1921, when it came under the jurisdiction of the newly-created Commonwealth Department Of Health, with the Director of Quarantine becoming the Director-General of Health. When the Portsea Quarantine Station was taken over by the Commonwealth in 1909, ‘it was upgraded over the next decade to meet standards systematically applied throughout the country’. Major works added to the complex during this period included extensions to the disinfecting and bathing complex, the rebuilding of Hospital No. 1, the construction of a new administration building and, in 1919, the construction of a number of timber emergency huts to accommodate returned servicemen during the influenza pandemic.But although the Commonwealth Government upgraded the Quarantine Station, it was also a period of the greatest demolitions. A number of early buildings were demolished at this time, including the original stone store and wooden hospital, Sullivan’s Cottage, early storekeeper’s quarters and the early police barracks.

The Disinfecting Complex

After the takeover by the Commonwealth the Disinfecting complex was further extended with the addition of three timber buildings: a clean luggage store (1910), a waiting room (1911), and a further shower block (c1925). The clean luggage store was extended (1916), a second disinfecting chamber was installed, and an extensive tramway system was installed, which linked all the components. It has been suggested, however that some kind of tramway system may have been employed prior to 1916, ‘as it is difficult to understand how the 1900 disinfecting chamber could operate without the system’.Power argues that this group of buildings is arguably ‘functionally the most prominent in the Station, in that all landed passengers were subject to this process, as the first contact with the Station’. Power considers that the group has ‘significant architectural merit’ and that functionally, they are ‘of national significance as the first of their type and a model for similar complexes throughout Australia, the first of which was erected some twelve years later. They represent a response to the period of greatest change in the understanding of infectious diseases, as the culmination of the work of Pasteur, Lister, Koch, etc.’ The complex is substantially intact.

A c1920 site plan shows the relationship of the buildings in this important precinct, while a series of c1900 photographs show how the red brick chimneys ‘dominate as they rise high above the roof’. The quarantine jetty (discussed earlier), constructed in 1858-59 with modifications in 1884, 1916 and 1938, was an important part of this precinct.

The Isolation Compound

A new timber isolation compound was erected between 1916 and 1920 to complement Hospital No. 5. (Buildings Nos. 65, 66 and No. 25.) The morgue was added in 1921. According to Power, the floor plan of the hospital was similar to the isolation hospital built in Brisbane in c1915. It seems likely that the Portsea building was modelled on the Brisbane structure. The observation block in Hospital No. 5 (Building No. 25) was upgraded.The isolation compound was an important component of the operations of the Quarantine Station and remains substantially intact. Known now as Buildings 65, 66 with the Morgue and Mortuary as Building No. 67, the isolation compound became the Officer Cadet School’s medical centre in the 1950s.

A dining room and kitchen were added in 1913 behind Hospitals Nos. 3 and 4 (Buildings Nos. 18, 16, 22). Three years later, in 1916, Hospital No. 1 was burned down.

Hospital No. 1

An architectural drawing dated 4 November 1919 confirmed that the rebuilt Hospital No. 1, constructed of brick rather than stone, was in a similar style to the original building but not to the 1850s design. The 1919 block plan showed ground and first floor plans and north and south elevations. The verandah facade seemed similar in appearance to the earlier hospital buildings but an examination of the ground and first floor plans suggested certain differences. A feature of the ground floor was the sizeable card and billiard rooms at one end and reading and writing rooms at the other. Held in National Archives among a collection of Commonwealth Department of Works Drawings, this 1919 plan was signed ‘PHB’ or ‘RHB’. Refer to figure 12.Administrative Building

The new Administrative Building constructed by the Commonwealth in 1916-17 is thought to have been designed by the architect J.S. Murdoch. An examination of architectural drawings of the building held in National Archives failed to confirm Murdoch’s involvement. An original plan of the ‘New Administrative Building’ prepared by the Commonwealth Department of Home Affairs, Contract C15-16, showed the north, south and west elevations. The clock tower was a notable feature. (The clock was removed in the 1940s.) The plan was unsigned. Refer to Figure 7.Another plan dated 24/11/16 and signed ‘PHB’ or ‘RHB’ showed the ground plan of the Administrative Block. Refer to Figure 12.

This building consolidated all the administrative functions under one roof and included police quarters, offices, doctor’s consulting room and a post office. It has been described as ‘a pleasing and significant example of colonial revival architecture’.

John Smith Murdoch (1862 – 1945)

Murdoch was Australia’s first Commonwealth Government Architect. He emigrated from Scotland in 1855 and worked for a brief period with the eminent Melbourne architectural firm Reed, Henderson and Smart. Six months later Murdoch was induced by John James Clark, Colonial Architect of the Queensland Public Works Department to take up a drafting position in Queensland. He had become Second Assistant Architect by 1904, his most successful Queensland work including various customs houses, post offices and rural township courthouses.After he joined the fledgling Commonwealth Department of Home Affairs in Melbourne, Murdoch in 1910 designed the Commonwealth Offices building in Treasury Place, Melbourne. Later, in 1913, Murdoch designed the Spencer Street Parcels Post Building, Melbourne. From this period and into the 1920s he was responsible for designing the buildings and/or layouts of several military installations around the country, including the Maribyrnong Cordite factory complex, Victoria; Flinders Naval Base, Victoria; Naval College, Jervis Bay; Fremantle Military Barracks, Queensland; Point Cook Flying School, Victoria; and additions to the Victorian Barracks, St Kilda Road, Melbourne.

In 1914, Murdoch became Commonwealth Architect and in 1919 Chief Architect. In the 1920s, Murdoch worked towards the establishment of a national architectural image for the Commonwealth Government. His ‘streamlined Classical modern Renaissance idiom – employed for his design for Old Parliament House and the Secretarial Buildings, Canberra, and numerous other buildings throughout the country – became Murdoch’s enduring legacy’. He died in 1945, ‘having designed many hundreds of Government buildings throughout Australia’.

The Army emergency huts

There was a period of increased activity at the Portsea Quarantine Station as the First World War drew to an end. According to O’Neill, almost 300 ships with over 11,800 passengers were quarantined at Point Nepean between November 1918 and August 1919. The total number of passengers processed at the Quarantine Station during this period is said to be 100,000 with 11,800 kept at the station. In 1919, twelve timber emergency huts were erected at the Quarantine Station to accommodate returned servicemen during the influenza pandemic. Major J.H. Welch in his history of the Station includes a 1965 photograph of some of these huts, which appear to be of a standard design. The huts, which are of historic interest as an example of the Army’s early associations with the Quarantine Station, remain.The Flagpole

A plan of a 50-foot high flagpole designed for the Station and signed by ‘FIW’ indicated its front and side elevations. The plan was dated 8 September 1919 and related to the time when the Army huts were constructed. This flagpole remains on the main Parade Ground, which is used still by Army officers. Refer to figure 11. Also two additional flagpoles of the same construction type remain at the complex. Both have lost their crosspiece but the main shaft remains. They are located at the point north of PMQ 1040 and close to PMQ 1038 as shown on Drawing PQ02/C.Site Plans 1916 and 1920

An examination of site plans dating from 1916 and 1920 indicated how the Quarantine Station complex had developed by this time. Buildings, other structures, roads and paths, and fencing were documented on these plans. The Station was shown surrounded by extensive areas of ti-tree scrub. A plan of the Defence and Quarantine Reserves dated 23 October 1916 (with later information) confirmed the regrading of the old Military (now Defence) Road in that year. Coles Track (then unnamed) was shown as a made road in the vicinity of the Quarantine Station entrance but a mere track as it approached the cluster of quarantine buildings. This track joined up with a track down to the London Bridge area at the Back Beach. The ‘approximate position of 12 Huts’ was noted south of the Isolation compound area.A later, 1920 plan, of the Quarantine Area at Point Nepean signed ‘PHB’ (figure 13) indicated the five major precincts that still formed the layout of the complex: the disinfecting precinct close to the jetty; the five hospitals well spaced along the foreshore; the matron’s cottage and doctor’s residence (the 1890s Medical Superintendent’s Residence) located on the rise behind the rebuilt Hospital No. 1; and the isolation compound, now enclosed behind a galvanized iron fence, at the western end of the complex. The Military Road to the south of the Quarantine Station and the track from the entrance, which became a ‘formed road’ as it passed through the complex, were both clearly marked. Each building, block of buildings, and other structures now had a number. A ‘List of Buildings’ at the bottom of the plan explained the use of each. A ‘lookout’ marked near the coast may have been the old flagpole, which warned of approaching vessels. This historic flagpole still exists. A ‘caretakers office’ shown near Hospital No.2 was the original stone surgery demolished much later, probably about 1960. The Shepherd’s Hut was shown as the dispensary. The group of 12 Army huts was also shown on this plan. A careful examination of this 1920 plan confirmed that, although some earlier buildings had gone, the original layout was still intact.

THE ARMY PERIODBy the early 1950s the use of the Portsea Quarantine Station was declining. After the Second World War improved medical knowledge, including the gradual eradication of smallpox, once a major scourge, and the provision of better facilities on board ships, ‘meant that there was a limited call on the services of the Quarantine Station’. It was reported that only 12 people were quarantined at the Portsea Station between 1954 and 1967.

Meanwhile, the Army had been looking for a suitable site for the establishment of an Officer Cadet School, that would be complementary to the Royal Military College at Duntroon (RMC Duntroon). In 1951, an agreement was reached between the Departments of Army and Health confirming that the Army could have temporary use of part of the Portsea complex. Until this date ‘the relationship between the Army and the Quarantine Station staff was cordial but remote’. The Defence Reserve of 420 acres was used for bivouacs on occasional weekends but no permanent staffing was attempted. However, during the influenza pandemic following the First World War, 12 emergency huts were erected at the Station to accommodate returned servicemen patients. These huts remain.

When the Army failed to locate a suitable alternative site for the Officer Cadet School (OCS) in the 1950s, it was given permissive occupancy of a number of Quarantine Station buildings.

The Army agreed to evacuate the Station within 24 hours in cases of ‘active quarantine’.

An examination of 1950s site plans prepared for the Army confirmed that there had been few changes in the complex between the 1920s and 1950s.

During the 1950s and 1960s the Army made modifications to some of the Quarantine Station buildings so that they could be used for accommodation and other purposes. Later, in the 1960s, the Army constructed a number of new buildings for the Officer Cadet School.

There was a brief resumption of quarantine activity at the Station in the 1970s with the opening of Tullamarine Airport when Melbourne became the first point of entry for many international flights. It was necessary to detain those who refused or were medically unable to undergo smallpox vaccination. This brought large numbers of quarantines to the Station. To meet the need for more accommodation, the Commonwealth Department of Health constructed two new buildings: the F.E. Cox Block (1972) and the J.H.L. Cumpston Block (1974). However, in 1974, the Station ceased to receive quarantines from Tullamarine, who were sent instead to the Fairfield Infectious Diseases Hospital. One of the new buildings was never used for quarantine purposes and both became Army residences. In 1978, the Department of Health declared all the Quarantine Station land, buildings and improvements surplus to requirements with the exception of the boiler house, which included the Museum, and two cottages. The Quarantine Station effectively ceased operation from this date. The two cottages were declared surplus in February 1980 upon the final vacation of the Quarantine Station by the Department of Health. The Station was finally closed by proclamation on 2 August 1980. The Army continued in occupation during the 1980s.

THE QUARANTINE STATION IN THE 1950S

A number of site plans of the 1950s, held in the National Archives, showed the Quarantine Station complex as it was at the time of the Army occupation. As in the 1920 plan discussed above, the Station buildings were named and numbered. Because of the Army’s commitment to making modifications, alterations and additions (particularly to the interiors of the buildings) rather than carrying out demolitions, most of the major buildings shown on the 1950s plans remain today. These included the most important buildings constructed in the 1850s and the upgraded buildings of the early decades of the 20th century. The complex, in fact, looks much the same today except for the addition of several new Army buildings in the 1960s, the two new Department of Health buildings in the 1970s, and landscaping changes made by the Army to a site once largely covered by ti-tree scrub.

A 1950 plan of Engineering Services at the Quarantine Station, prepared by the Commonwealth Department of Works and Housing, Victorian/Tasmanian Branch, again showed the complex’s important precincts. These included the Isolation Hospital block enclosed by a galvanized iron fence, the Disinfecting and Bath block, the five hospitals, the administrative block, the precinct around the matron’s and medical superintendent’s residences, and the cottages at the Portsea Road entrance. Survey notes indicated that there was concern about the wharf, jetty (removed in 1973) and boat shed area and the crumbling condition of the bayside seawalls. The flagpole on what became the Army’s main parade ground in front of the administration block was clearly marked. The Army emergency huts were shown as 14 again and consisted of 12 huts and two smaller ancillary buildings. A small Consumptive Block shown on earlier plans was indicated near the junction of Military Road and a bush track. This block most probably no longer exists. The map noted ti-tree scrub along the shoreline while the whole Station was surrounded by large areas of scrub.

THE OFFICER CADET SCHOOL, 1952-1984

The choice of the former Quarantine Station in the 1950s as the place to establish an Officer Cadet School adds to the historical significance of the Portsea complex for its associations with an important development in the history of the Australian Army. A major concern from the Federation years was the establishment of a self-sufficient and professional Australian Army and the ‘production of sufficient young officers trained to the level and in the manner the Army required’. This was seen as essential for the proper military defence of the new Commonwealth.

In 1909, the Australian Prime Minister, Alfred Deakin (1856-1919), who was particularly concerned about the nation’s defence and who supported universal military service as a patriotic duty, invited the legendary Lord Kitchener to visit Australia and advise on military defence. Kitchener, the foremost soldier in the British Empire, had played a major and successful role in 1900-1902 during the Boer War, although his scorched earth policy and treatment of prisoners have been criticized by some recent historians. Kitchener’s 1909 report recommended the creation of an Australian staff corps and an officer education institution. The staff corps was to be ‘drawn entirely from the proposed military college, given opportunities for study and attachment with other Empire armies abroad, and paid at a rate that would attract and retain men of the right stamp’. The model chosen by the Army for the Australian college was the U.S. Military Academy at West Point rather than Britain’s Sandhurst, ‘since this (i.e. West Point) provided a severe and thoroughly military training imposed by a Democratic Government’. West Point had been the model for a Royal Military College established by the Canadian Government at Kingston in 1896.

The Deakin Government rejected Kitchener’s suggestion that young men attending an Australian military college should pay for their education. It was thought that this would result in officer graduates coming from only affluent families as had been the case in the British Army.

RMC Duntroon

The first of a number of officer training schools established by the Australian Army was RMC Duntroon opened in Canberra with an intake of 42 staff cadets in 1911. However, only a handful of officers had graduated from Duntroon when war broke out in 1914. It became clear then and later that staff colleges could not produce enough young officers of a standard to meet the Army’s requirements. The procuring of officers and ex-officers from the British Army was the common response to this problem.Duntroon was closed in 1930 and its functions transferred to Victoria Barracks in Sydney but, in 1937, the RMC moved back to Duntroon. During the Second World War, there was more concern about the lack of trained young officers. After the war, Major-General George Vasey was assigned to report on the future direction of Duntroon and ‘the education and training of staff corps officers’.

The Cadet Officer School at Portsea

It was decided in 1950 to supplement RMC Duntroon with an Officer Cadet School at Portsea. Candidates would complete a six-month course before appointment as second lieutenants. The school opened at the Portsea Quarantine Station on 5 January 1952 and the first graduation parade took place on 6 June 1952. In 1955, the course was extended to 12 months.According to one account,

‘With less rigid entry requirements, Portsea became a vehicle for commissioning suitably qualified other ranks into the regular army, but its first class did not graduate until June 1952 and it thus provided only a partial solution to the difficulty created by the Korean War’. Young regular officers who graduated from Duntroon, and increasingly from Portsea, found themselves on active service for long periods, often as long as 20 years. That is, platoon commanders of the Korean War became battalion commanders in Vietnam.There was an attempt to recruit ex-officers and NCOs from the British Army to join the Australian Army as instructors but that yielded little. Australian Army Staff in London in the post-war years found only 359 suitable out of 2,860 applications.

The Military Board reported in February 1960 that there were ‘serious and impending shortages among junior offices in the ranks of captain and major’. In 1963, the Adjutant-General’s Branch convened a committee of inquiry into the problem. It found that the perception of an early retirement age and small pensions were significant factors in the failure to attract and retain men. By February 1967, it was reported that the regular army was 700 officers short, although the opening of an Officer Training Unit at Scheyville in New South Wales had produced ‘a surplus of lieutenants’. Once again, the Army fell back on recruiting officers from the British Army.

From this time, reflecting changed expectations in the broader community, the Army moved towards establishing tertiary education at RMC Duntroon to ‘attract young men of high calibre’. A full University program was instituted in 1967.

In 1984, the Officer Cadet School at Portsea was relocated to Canberra following the establishment of the Australian Defence Force Academy. This Academy, which admitted female Army Officers (previously segregated into the WRAAC), was opened in 1986 for recruit and officer cadet training.

A 1985 report summed up the achievements of the OCS at Portsea, which it claimed, had earned an international reputation, in these words:

‘Since the school’s establishment 3,166 officers have graduated. The course is designed primarily to produce career officers for all sections of the Australian Army. It is a twelve-month course, with intakes in January and July each year. Since 1957 overseas cadets representing sixteen different countries have graduated from the Officer Cadet School. (It) is firmly established as an international institution.’

The social interaction between the local people of Point Nepean and students and staff at the Officer Cadet School, and community use of the complex, is discussed in a later Section.

Quarantine buildings occupied by the Army

Among the major Station buildings occupied by the Officer Cadet School were the five Hospitals, which were used for Officers’ Accommodation (Nos. 1, 2 and 3), Officers and Cadets’ Accommodation (No. 4) and Sergeants’ Mess (No. 5). The Administration Building (constructed in 1916-17) became Army Headquarters, while the Medical Superintendent’s Residence of the 1890s became the Commanding Officers’ Residence. The Isolation Compound became the Officer Cadet School’s Medical Centre.New buildings, 1963-1965

A number of new buildings were constructed at the Quarantine Station between 1963 and 1965 for the Officer Cadet School, some of a substantial nature. These buildings, which cost a total of £300,000 included No. 3 Cadet Barracks (1963), Assembly Room and Library (1963), Guardhouse and Entrance Gates costing £3,500 (1963), Gymnasium costing £25,000 (1965), No. 4 Officer Cadet Barrack costing £75,000 (1965). The Assembly Room and Library was later named Badcoe Hall, after Major Peter Badcoe who trained at the Portsea Officer Cadet School. He was killed in Vietnam and awarded a Victoria Cross.In addition, the Army carried out extensive landscaping of the site. This included the planting between May 1965 and October 1966 of 3,000 pine trees and more than 2,000 eucalypts, sheoaks, bottle brush, casuarinas and other native trees and shrubs.

Parade Ground and Flagstaff

The main Parade Ground and Flagstaff used by the Army have particular historical significance for their associations with the Graduation Services, which the Officer Cadet School held there. Many local people attended these colourful ceremonies and also remember watching the polo matches played on the sports ground. Polo is still played at the complex with the permission of the Army. The Army retains its interest in the Parade Ground. An Army officer still raises three flags daily at the historic flagpole.SCHOOL OF ARMY HEALTH, 1985-1998