RELIGIOUS CENTRE MONASH UNIVERSITY

BUILDING 9 MONASH UNIVERSITY, 1-131 WELLINGTON ROAD CLAYTON, MONASH CITY

-

Add to tour

You must log in to do that.

-

Share

-

Shortlist place

You must log in to do that.

- Download report

Statement of Significance

What is significant?

The Monash Religious Centre, designed by John Mockridge of the Melbourne architectural firm Mockridge Stahle & Mitchell, was built in 1967-8 at the new Monash University. The university opened in 1961, and the Religious Centre was planned by the Christian and Jewish communities of Melbourne as a space that could be used by all religious groups. The funds were raised by the different groups and the building was then presented to the university, to dissociate it from any one religious tradition. The Religious Centre was seen at the time as an important ecumenical exercise and part of the process of reassessment and reform within the churches, including moves towards liturgical experimentation, greater social relevance and greater interaction with other religious traditions. Mockridge Stahle & Mitchell, with John Mockridge as the principal designer, was a prominent architectural firm established in Melbourne in 1948, and was particularly well-known for its designs for school and university buildings and churches. Mockridge chose the circular form of the building as a symbol of unity, eternity and ecumenical feeling. With the growth of a significant non-Western student population, the Centre has been increasingly used by other religious groups, particularly Muslims, Buddhists and Hindus. The building is used for Christian and Jewish services, Muslim prayers, Bible studies, Catholic confession, meetings of the religious societies, discussion groups and social gatherings, as well as joint ceremonies by representatives of the different users. The organ, made by Ronald Sharp of Sydney, was installed in 1978 in the Large Chapel, which is also used for organ practice, choir rehearsals, concerts, weddings and funerals.

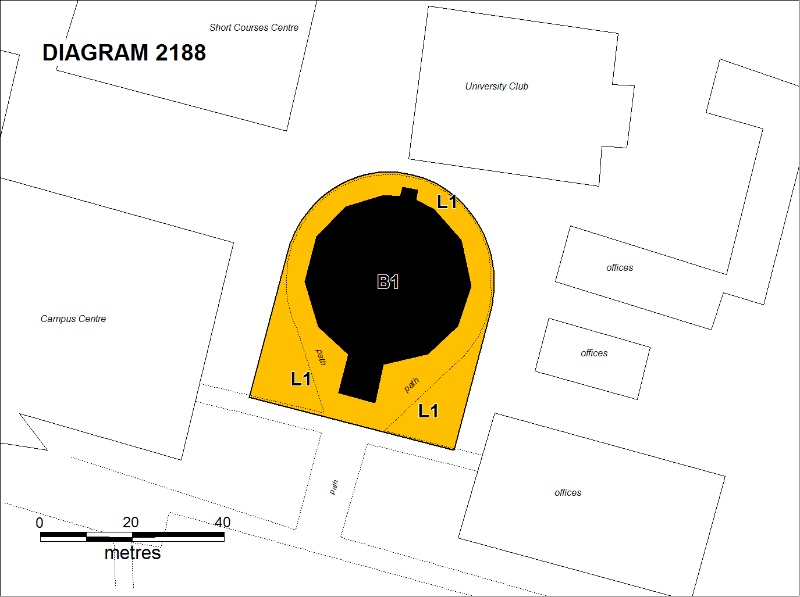

The Religious Centre is located in a central position at Monash University. It is circular in plan, with the large central chapel, of narrow inclined pre-cast concrete slabs with a quartz finish, rising above the smaller rooms of dark brick and redwood (originally unpainted) arranged around this. These smaller rooms, a rectangular narthex or meeting room at the main entrance, a rectangular second chapel on the side opposite this, several vestries, a sacristy, prayer rooms, toilets and a kitchen, open off an ambulatory, and have small courtyards in between intended as meeting places. The Large Chapel has a raised area and altar to the north and a prominent centre aisle leading from the large processional doors. Religious imagery has been avoided, and the narrow windows have stained glass with abstract designs by Les Kossatz. The rectangular Small Chapel contrasts with the open spaciousness of the Large Chapel. It was designed less ambiguously to be used for daily Mass, weekly Anglican Holy Communion and Protestant Sunday Services. Seating for about thirty is arranged in conventional rows facing a small sanctuary area, raised one step and flanked by stained glass windows designed by Leonard French. The other windows are narrow strips at the top and at the base of the side walls, allowing views only of the sky and of the water of the ponds on each side.

How is it significant?

The Monash Religious Centre is of architectural, historical, aesthetic and social significance to the state of Victoria.

Why is it significant?

The Monash Religious Centre is of historical significance as a reflection of the early ecumenical movement in Victoria, which encouraged greater experimentation in religious practice and more interaction and understanding between different religions. It was the first example in Australia of such a centre, which was funded by Christian and Jewish groups, but was presented to Monash University to be used by all religions.

The Monash Religious Centre is architecturally significant as a fine example of a religious building of the 1960s. It is notable for its centralised plan, symbolising unity, eternity and ecumenism, and as an example of the circular plans first used by Roy Grounds in the 1950s and adopted for a range of building types in the 1950s and 1960s. It is significant as a fine example of the work of John Mockridge of the Melbourne architectural firm Mockridge Stahle & Mitchell.

The Monash Religious Centre is socially significant as a combined place of worship for generations of university students and staff of all religions.

The Monash Religious Centre is aesthetically significant for its unusual design, in particular the design of the Small and Large Chapels and the stained glass by Les Kossatz and Leonard French.

-

-

RELIGIOUS CENTRE MONASH UNIVERSITY - History

CONTEXTUAL HISTORY

Clayton was the original campus of Monash University. Named after the prominent Australian Sir John Monash, Monash University was established by an Act of Parliament in 1958 and opened its doors for the first time in 1961. The 100 hectares of open field had previously been used for a variety of purposes, including the Talbot Epileptic Colony, before being bought for the university. From its first intake of 347 students at Clayton in 1961 the University grew rapidly in size and student numbers so that by 1967 it had more than 7000 students.

As Philip Goad notes in Melbourne Architecture, p 175:

In the late 1950s churches, schools and universities, traditionally enlightened patrons of architecture began, after an absence of nearly twenty years, to commission buildings. Some of the period's most important free-standing public buildings are found on the old and new campuses, and along the outer highways. While the new architecture, with its emphasis on human scale, rational planning, climate and comfort control, was eminently suitable for educational buildings such as Preshil School, the churches of the times, much like religion itself, seemed alien to the new world. Bogle & Banfield's St James Anglican Church and Mockridge Stahle & Mitchell's St Faith's Anglican Church were two such startling new arrivals.

According to Joe Rollo in Contemporary Melbourne Architecture (p 37) Victoria's universities have been at the forefront of architecture in the state, and Monash University has commissioned a body of built work by some of Australia's finest architects, such as Daryl Jackson, Bates Smart McCutcheon, Allan Powell, Denton Corker Marshall and Woods Bagot, and he considers that two early structures, the Religious Centre and the Robert Blackwood Hall (1972, by Sir Roy Grounds) helped set the architectural standards at Monash.

Circular plans were introduced to Victorian architecture by the architect Roy Grounds, who in the 1950s adopted platonic geometric shapes of circles, squares and triangles for plan forms, for example he designed a triangular house in Studley Street, Kew in 1951, and a circular house for the Henty family at Frankston in 1952, and used it on a larger scale for the Academy of Sciences Building in Canberra (1959). Other architects, notably Mockridge Stahle & Mitchell, used the circular form for religious buildings such as St Faith's Anglican Church at Burwood (1957-8), and for Whitley College at Parkville (1962-5); and Oakley and Parkes used a similar plan for the lobby of the Brighton Municipal Offices (1959-60).

John Mockridge and Mockridge Stahle & Mitchell

[taken from the RMIT website, 'Modern in Melbourne', and from the transcript of an oral history interview with John Mockridge in the National Library of Australia (Oral TRC 1/696)]

John Mockridge was born in Geelong, went to school at Geelong College and later studied for three years at the Gordon Institute of Technology in Geelong. He ascribes his belief in the association between architecture and the other arts to the influence of the headmaster at the Gordon Institute, George King. He completed his at the University of Melbourne just before WWII, and then joined the Air Force and was posted to Darwin, where he spent about eighteen months before being posted back to Melbourne. Upon discharge he joined the Department of the Interior (the Commonwealth Department of Works), then worked for Buchan Laird & Buchan, where he met James Stahle, as well as having a small private practice. He designed several houses, won some competitions and had some articles published. After two and a half years at Buchan Laid & Buchan he and Stahle took up tutoring jobs at the Atelier at Melbourne University and started a joint practice. He went overseas for two years, working in London and Paris.

In 1948 together with George Mitchell they formed the practice of Mockridge Stahle & Mitchell. In the early days of the practice all three principals assisted in design, documentation and drafting, but this arrangement soon became impractical. Mockridge was strong in design, Stahle in specifications and Mitchell in administration, and Mockridge acting as the principal designer throughout most of the practice's years of operation. However prior to sketch design the partners exchanged ideas about how the design should be approached. At first they designed mainly houses, mostly holiday houses on the Mornington Peninsula, but as the practice grew and began to get large school and university commissions, houses became less viable.

John Mockridge cited as important design influences firstly the work of Californian architect William Wurster, and also of Mies van der Rohe (particularly his use of classicism), Richard Neutra and, to a lesser extent, Le Corbusier.

The firm designed many buildings for Melbourne Grammar: the boat house (1953), the Centenary Building, Myer Music School, Music Master's Residence and Grimwade Science Wing (all 1958), and the New School House, Wadhurst Library and Grimwade House Stage 2 (all 1966), and for Brighton Grammar: Library and Assembly Hall (1953), Sports Pavilion (1956), classrooms (1958), science wing (1964), and Centenary Hall (1966). They became associated with school architecture (in Victoria and the ACT) and also designed university buildings for the Australian National University, the University of Melbourne and Monash University.

Their religious buildings include the Church of the Mother of God, East Ivanhoe (1957), St Faith's Church of England, Burwood, Church of Mary Immaculate and Presbytery, Ivanhoe, and St Marks Church of England Sunshine (all 1958), St George's Church of England, Reservoir and Whitley Baptist College, Parkville (1964), Church of St Michael and All Angels, Beaumaris, the Monash University Religious Centre, the Ridley College Chapel, Parkville, and the Holy Trinity Church of England, Doncaster (1966).

They also designed many houses, as well as the Mitchell Valley Motel in Bairnsdale (1958, demolished), and the Camberwell Civic Centre and Municipal Offices (1966).

HISTORY OF PLACE

[Adapted from Peter Janssen's History of the Religious Centre [no title], 1984]

During the 1950s there was some discussion regarding the place of religion within an Australian secular university. At the University of Melbourne the various churches had their own colleges and chapels, which were separate from the university. When plans were announced for the establishment of a new university in the growing south-east suburbs of Melbourne it allowed for fresh ideas regarding the incorporation of religion into a modern University.

In 1958 representatives of the five major Christian denominations proposed that this religious presence at the new Monash University be provided by a Chaplaincy Centre and Collegiate Library, which could be used by all disciplines and could promote a unified view of Christianity. It was thought that difficulties could arise in the provision of facilities for specific religious groups and possible discrimination between them, given the potentially large range of religions on campus, especially given the limits on space. This early proposal was basically Christian, but the proposal did contain provision for small discussion rooms for use by other faiths. By 1961 however this plan had been rejected by the University Council.

With the opening of the university in 1961, and with no religious facilities provided, it was suggested that perhaps a building might be found, among those which had been acquired with the site, which was not needed for other purposes. The Red Cross Cottage was set aside as a temporary Religious Centre.

In 1962 the Vice-Chancellor suggested to the churches that they begin to consider plans for a permanent Religious Centre. The experience of the Red Cross Cottage, where chapels were shared, had demonstrated that the same space could be used by different denominations. The churches stressed that the Centre would be open to members of all bodies holding 'coherent religious beliefs', and that 'all religious bodies should be able to come together in the one place; short of a common place of worship they should be able to share the same Common Room and facilities'.

The use of a common facility was to some extent pragmatic, as the various denominations knew that the University would not be able to grant them individual facilities, and they did not have the resources to fund their own. It was also hoped that day-to-day cooperation would increase ecumenical awareness.

The churches thought it proper that the Centre be owned and controlled by the University, partly to dissociate it from any one religious body or tradition. In December 1963 Council gave permission for a private appeal for funds and began the selection of a site. By April 1964 John Mockridge, of the architectural firm Mockridge Stahle & Mitchell, had been approved as architect, and in May the Buildings Committee of Council set up a Religious Centre Project Sub-Committee whose primary task was to work with the architect on details of the building so that it would be compatible with the other campus buildings. Funding for the building was organised by the Churches and the Jewish community as a gift to the university, which is probably unique amongst Australian universities. The funding was undertaken by the churches independently while Monash University was seeking funding for the other university buildings.

In October 1963 the churches had already presented to Council plans for a building incorporating one large chapel with seating for five hundred, and a small chapel for fifty, with five vestries with sliding doors to create larger areas if required, a common room, kitchen, toilets and a storeroom. The architect's design followed this brief, and located the Small Chapel, vestries, narthex/common room and other facilities around a circular Large Chapel, which would be completely enclosed by the outer ring of smaller rooms. The Large Chapel was to be 75 feet in diameter and 36 feet high, so the chapel could rise dramatically above the smaller rooms surrounding it.

The Sub-Committee approved the basic design, although plans for a perspex dome above the Large Chapel were abandoned, and the degree of inward inclination of the walls was increased, with ribbing and fluting of the external wall to break the surface and create its crown-lie appearance. It was also decided to line the Large Chapel's walls with vertical battens to improve acoustics and place a skylight over the altar.

Construction, by Fulton Constructions, began in March 1967, with the first peg driven by the Premier Henry Bolte (Later Sir Henry) who at the ceremony announced a gift of $20,000 from the State Government. The foundation stone was laid on 4 April 1967 by the Governor, His Excellency Sir Rohan Delacombe. The building was completed fourteen months later and the opening ceremony took place on 9 June 1968, with a joint dedication preformed by the chaplains and the key presented to the Chancellor by Archbishop Woods, symbolising the final presentation of the religious Centre to the University by the Churches who had brought it into being.

The Religious Centre project was widely reported in Melbourne newspapers. It was seen as an important ecumenical exercise at a time when ecumenism was not yet respectable. Further interest arose from the fact that the Centre was the first of its kind in Australia. The opening was perceived as part of the process of reassessment and reform within the Christian churches and of a sharpening political climate within the universities at the time. During the 1960s there were movements within the Christian churches towards self-criticism in the face of political changes, theological innovation, and apparent democratisation and laicisation of other institutions in Western society. Such movements emphasised liturgical experimentation, lay participation and greater social relevance and political activism in the church's mission. Along with considerations of internal reform came moves for greater ecumenical ties among churches and greater interaction with other religious and ethical traditions.

With the development of the University and the growth of a significant non-Western student population, religious practices other than Jewish or Christian became manifest, particularly Islamic, Buddhist and Hindu. The two Chapels are predominantly Christian in terms of their use, but other areas are commonly used by all groups. The use by Islamic students was so great that they paid for the installation of special footbaths for the ablutions prior to prayer. The typical form of worship in the Centre is separate, but the Centre has been the site of joint ceremonies by representatives of the major users, such as the dedication ceremony (1968); the tenth anniversary service and dedication of the organ (1978); combined ceremonies to witness the investiture of chaplains; several interfaith dialogues in 1978 between the Evangelical Union and the Jewish Students' Society; and a series of discussions in 1979 on issues connected with Christianity, Judaism and Islam. The dualism of worship is seen in the design of the building, with the large Chapel rising from within a ring of small private spaces, which might be used at various times for Muslim prayer, Bible studies, Catholic Confession, meetings between members of the religious societies, discussion groups, social gatherings, Mass (in the Small chapel), and eastern meditation. One of the achievements of the Centre is considered to have been in helping to create trust between the members of the various traditions.

The building is used for organ practice, choir rehearsals, concerts and recitals, weddings, funerals and memorial services. The organ was made by Ronald Sharp of Sydney (who among other organs built the organ in the Sydney Opera House and installed in 1978. Since then there have been an annual series of organ recitals with local and international organists, and Monash has been one of the venues in the annual Melbourne festival of organ and harpsichord.

John Mockridge recorded an interview about his life and work in 1973 with Hazel de Berg (National Library of Australia, Oral TRC 1/696) in which he makes particular mention of the Monash Religious Centre. He notes the use of precast concrete for the building, and commented that 'modern techniques make it reasonably simple to produce [large volumes] with a minimum of expense, and thereby create some sort of drama which in olden days would have been difficult to do, or expensive to do'. He designed a circular chapel for the Religious Centre

because I felt it expressed unity and eternity and an ecumenical feeling which was abroad at the university. There is a smaller chapel attached to the large one and this is just a simple rectangular shape and there are a series of rooms, meeting rooms and vestries, around the perimeter of the main chapel connected by an ambulatory and which have little courtyards where little meetings can be held between these various wings which protrude from the circular fan shape. There is a large narthex which is really an entrance hall in church parlance and which is used also as a meeting room for people who don't have a recognised religion. This is quite interesting, in that when I was designing it I did ask the committee, headed by the Vice Chancellor, whether there'd be weddings held there and they seemed to think there wouldn't be any at all, but it is an extraordinarily popular building for weddings, as it turned out over recent years.

Externally it has been tied together with the other buildings on the campus which have a rigid palette, I suppose you'd call it, of materials, manganese brown bricks and white precast panels with quartz finishes. I used these materials and I used quite a bit of Californian redwood in large sizes, which look nice and chunky and strong. The brown manganese bricks I used in the new size at the time, which is 12" long instead of 9" long, that brick has been used quite a lot since, not only at Monash but all over Melbourne. It's a rather more expensive brick but it's interesting in scale.

He also noted that 'I've always been very much in favour of trying to combine art with architecture, because traditionally this had been the case .', and that 'To me, architecture is inextricable tied up with all the other arts, with music whether it be good classical or good jazz, with the drama, with the ballet, with sculpture and with painting and with good writing. It's just a matter of how you feel'.

RELIGIOUS CENTRE MONASH UNIVERSITY - Assessment Against Criteria

a. Importance to the course, or pattern, of Victoria's cultural history

The Monash Religious Centre is a reflection of the early ecumenical movement in Victoria, which encouraged greater experimentation in religious practice and more interaction and understanding between different religions. It was the first example in Australia of such a centre, which was funded by Christian and Jewish groups, but was presented to Monash University to be used by all religions.

b. Possession of uncommon, rare or endangered aspects of Victoria's cultural history.

c. Potential to yield information that will contribute to an understanding of Victoria's cultural history.

d. Importance in demonstrating the principal characteristics of a class of culturalplaces or environments.

The Monash Religious Centre is a fine example of a religious building of the 1960s. It is notable for its centralised plan, symbolising unity, eternity and ecumenism, an example of the circular plans first used by Roy Grounds in the 1950s and adopted for a range of building types in the 1950s and 1960s. It is significant as a major work of John Mockridge, of the Melbourne architectural firm Mockridge Stahle & Mitchell.

e. Importance in exhibiting particular aesthetic characteristics.

The Monash Religious Centre is aesthetically significant for its unusual design, in particular the design of the Small and Large Chapels and the stained glass by Les Kossatz and Leonard French.

f. Importance in demonstrating a high degree of creative or technical achievement at aparticular period.

g. Strong or special association with a particular community or cultural group for social,cultural or spiritual reasons.This includes the significance of a place to Indigenouspeoples as part of their continuing and developing cultural traditions.

The Monash Religious Centre is socially significant as a combined place of worship for generations of university students and staff of all religions at Monash University.

h. Special association with the life or works of a person, or group of persons, ofimportance in Victoria's history.

RELIGIOUS CENTRE MONASH UNIVERSITY - Plaque Citation

Designed by John Mockridge and built in 1967-8 this centre was funded by the Christian and Jewish communities of Melbourne and presented to Monash University for use by all religious groups.

RELIGIOUS CENTRE MONASH UNIVERSITY - Permit Exemptions

General Exemptions:General exemptions apply to all places and objects included in the Victorian Heritage Register (VHR). General exemptions have been designed to allow everyday activities, maintenance and changes to your property, which don’t harm its cultural heritage significance, to proceed without the need to obtain approvals under the Heritage Act 2017.Places of worship: In some circumstances, you can alter a place of worship to accommodate religious practices without a permit, but you must notify the Executive Director of Heritage Victoria before you start the works or activities at least 20 business days before the works or activities are to commence.Subdivision/consolidation: Permit exemptions exist for some subdivisions and consolidations. If the subdivision or consolidation is in accordance with a planning permit granted under Part 4 of the Planning and Environment Act 1987 and the application for the planning permit was referred to the Executive Director of Heritage Victoria as a determining referral authority, a permit is not required.Specific exemptions may also apply to your registered place or object. If applicable, these are listed below. Specific exemptions are tailored to the conservation and management needs of an individual registered place or object and set out works and activities that are exempt from the requirements of a permit. Specific exemptions prevail if they conflict with general exemptions. Find out more about heritage permit exemptions here.Specific Exemptions:General Conditions: 1. All exempted alterations are to be planned and carried out in a manner which prevents damage to the fabric of the registered place or object. General Conditions: 2. Should it become apparent during further inspection or the carrying out of works that original or previously hidden or inaccessible details of the place or object are revealed which relate to the significance of the place or object, then the exemption covering such works shall cease and Heritage Victoria shall be notified as soon as possible. General Conditions: 3. If there is a conservation policy and plan endorsed by the Executive Director, all works shall be in accordance with it. Note: The existence of a Conservation Management Plan or a Heritage Action Plan endorsed by the Executive Director, Heritage Victoria provides guidance for the management of the heritage values associated with the site. It may not be necessary to obtain a heritage permit for certain works specified in the management plan. General Conditions: 4. Nothing in this determination prevents the Executive Director from amending or rescinding all or any of the permit exemptions. General Conditions: 5. Nothing in this determination exempts owners or their agents from the responsibility to seek relevant planning or building permits from the responsible authorities where applicable. Minor Works : Note: Any Minor Works that in the opinion of the Executive Director will not adversely affect the heritage significance of the place may be exempt from the permit requirements of the Heritage Act. A person proposing to undertake minor works may submit a proposal to the Executive Director. If the Executive Director is satisfied that the proposed works will not adversely affect the heritage values of the site, the applicant may be exempted from the requirement to obtain a heritage permit. If an applicant is uncertain whether a heritage permit is required, it is recommended that the permits co-ordinator be contacted. The process of gardening, including mowing, hedge clipping, bedding displays, removal of dead plants and replanting of the gardens and the lawn areas to the south of the Centre are exempt from permit, as are works to the paths surrounding the building.RELIGIOUS CENTRE MONASH UNIVERSITY - Permit Exemption Policy

The purpose of the Permit Policy is to assist when considering or making decisions regarding works to the place. It is recommended that any proposed works be discussed with an officer of Heritage Victoria prior to them being undertaken or a permit is applied for. Discussing any proposed works will assist in answering any questions the owner may have and aid any decisions regarding works to the place. It is recommended that a Conservation Management Plan is undertaken to assist with the future management of the cultural significance of the place.

The addition of new buildings to the site may impact upon the cultural heritage significance of the place and will require a permit. The purpose of this requirement is not to prevent any further development on this site, but to enable control of possible adverse impacts on heritage significance during that process.

The significance of the place lies in its rarity and intactness as a notable example of a1960s building with a circular plan, which was built for, and continues to be used by, all religious groups at the university. Any alterations that impact on its significance are subject to permit application. All original elements of the building should be retained.

-

-

-

-

-

RELIGIOUS CENTRE MONASH UNIVERSITY

Victorian Heritage Register H2188

Victorian Heritage Register H2188 -

Religious Centre Monash University

National Trust H2188

National Trust H2188 -

Erythrina sp.

National Trust

National Trust

-

Abruzzo Club

Merri-bek City

Merri-bek City -

-

Albanian Mosque

Yarra City

Yarra City

-

-