DEAF CHILDREN AUSTRALIA (FORMER VICTORIAN DEAF AND DUMB INSTITUTION)

583-597 ST KILDA ROAD MELBOURNE, MELBOURNE CITY

-

Add to tour

You must log in to do that.

-

Share

-

Shortlist place

You must log in to do that.

- Download report

Statement of Significance

What is significant?

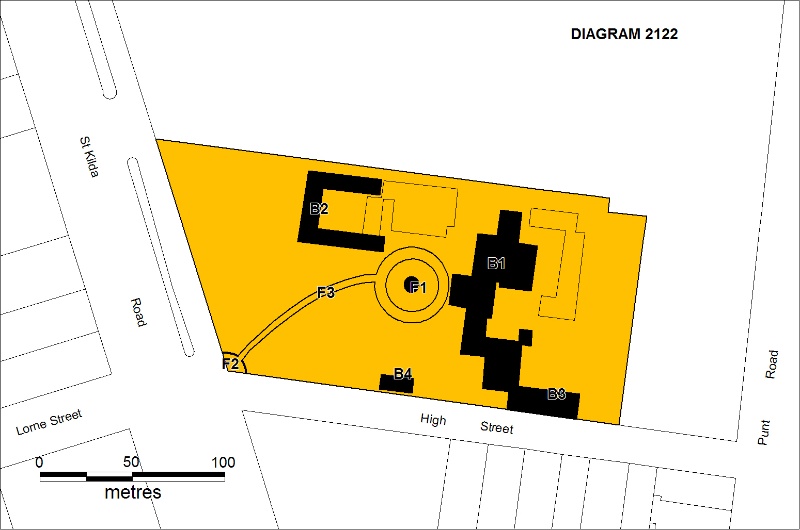

The Victorian College for the Deaf (formerly known as the Victorian Deaf and Dumb Institution) was built in 1866 to provide a home, education and vocational training for deaf and dumb children. The first school for deaf and dumb children in Victoria had been established in 1860 in Prahran by Frederick Rose, and this moved into larger premises as enrolments increased. In 1864 a committee of prominent citizens obtained a grant of land for the new institution, as well as £3000, from the government, raised £1654 more by public subscription, and commissioned the architects Crouch and Wilson to design the building, the first part of which was built in 1866, and the remainder in 1871. Rose was the first Superintendent and his wife the first Matron. The grounds were enhanced in the 1860s by gifts of plants and seeds from Baron von Mueller. Various additions have been made over the years, including bluestone extensions to the north and south of the main building, and the red brick Fenton Memorial Hall (c1950). In 1913 the school was taken over by the Department of Education as State School no 3774, and a new school building was constructed in the front garden in 1928. A brick trade block for teaching trades to the boys was added in c1940. The Institution was used by the RAAF in 1942-44. Enrolments peaked in the 1950s following a rubella epidemic in 1941-2, and a number of new buildings were added between 1949 and 1985. However with more schools for the deaf and dumb opening and advances in the treatment of the deaf, enrolments decreased. The name was changed in 1949 to the Victorian School for Deaf Children, and is now known as Deaf Children Australia. The main building is now used for administration, with the school in the newer buildings in front. The institution has an extensive collection of objects relating to the history of the place, including furniture, artefacts, architectural drawings, photographs and other archival material.

The Victorian College for the Deaf lies at the corner of St Kilda Road and High Street with the main building set back behind extensive gardens with mature trees and a curved tree-lined driveway. The nineteenth century block is an imposing symmetrical Gothic Revival building, forming a U-shape around a rear courtyard with a mature camphor laurel tree. It has a central three storey section surmounted by a tower and spire above the main entrance, subsidiary towers behind the gabled flanking pavilions, and recessed two storey L-shaped wings to the south and north, all above a semi-basement. The walls are of tuckpointed bluestone, and there are decorative red and cream brick and cement dressings around the door and window openings. The walls are decorated with Greek cross-shaped ceramic blocks with quatrefoil openings. The roofs are slate and chimneys are patterned bichrome brick. The trade block at the rear is a single storey building of clinker bricks with two large arched metal-framed windows. The 1928 school building in the front garden is a single storey rendered brick building set around an internal courtyard.

How is it significant?

The Victorian College for the Deaf is of historical, architectural and social significance to the state of Victoria.

Why is it significant?

The Victorian College for the Deaf is historically significant for its role as the first major institution in Australia built for the teaching and care of deaf children. It pioneered the teaching of Victorian children with substantial hearing problems, has been at the forefront of developments in the teaching of the deaf, and has played an important role in the history of education in Victoria. It is historically significant for its association with the prosperous and confident post gold rush period, when many of Melbourne's major educational, health and social welfare institutions were established in response to the public desire to assist disadvantaged groups.

The Victorian College for the Deaf is architecturally significant as an imposing and intact example of a major Gothic Revival style institutional building, which when built was of a scale and style unmatched by earlier Melbourne institutions. It is an important example of the work of the prominent Melbourne architectural practice of Crouch & Wilson. The practice designed a number of important public buildings in Victoria, including Methodist Ladies' College, the Prahran Town Hall, The Homeopathic (later Prince Henry's) Hospital, the Royal Victorian Institute for the Blind, and numerous churches, as well as major buildings in Tasmania, Queensland and New Zealand. The large site with its tree lined drive and circular garden provide a picturesque setting for the building. Together with the Victorian School for the Blind and Wesley College, all of which have extensive grounds facing St Kilda Road, it forms a significant part of the St Kilda Road streetscape, and part of one of Melbourne's most important institutional precincts.

The Victorian College for the Deaf is of social significance for its continuing association with the teaching of deaf children in Victoria, an association which has continued up to the present day. As deafness can be hereditary, sometimes several generations of the same family have attended the school, and it is held in fond regard by past students, whose education and training in the school has allowed them to enter the workforce and more easily communicate with the wider community.

-

-

DEAF CHILDREN AUSTRALIA (FORMER VICTORIAN DEAF AND DUMB INSTITUTION) - History

CONTEXTUAL HISTORY

Until the late eighteenth century it was regarded a hopeless to attempt to educate the deaf, who then faced insurmountable problems in acquiring and using language. By the nineteenth century it was being realised that deaf children could be educated, and could be taught to communicate using either manual systems of hand signs or oral systems based on teaching speech and lip reading.

After the 1850s gold rushes Melbourne became Australia's largest and wealthiest city and one of the fastest growing cities in the world. It also became much more respectable, and the disadvantaged, particularly children, became the focus of much middle class concern. During the 1850s and 1860s a number of institutions, such as hospitals, industrial schools and asylums, were established to provide for those colonists unable to provide for themselves. [Buckrich, Lighthouse on the Boulevard, pp 1-9.] In the 1850s, though St Kilda Road was still an unmade road through open country, a number of institutions had already been established there: the Immigrants Aid Society Depot, the Military Barracks and the Diocesan School (later Melbourne Grammar School).

Until 1860 there was no education provided for deaf children in Australia. The first School for the Deaf and Dumb, with one pupil, was then established in his house in Prahran by Frederick John Rose. Rose was a deaf mute man working until then as a builder in Bendigo, who had been educated at the Old Kent Road Institution for the Deaf and Dumb in London. In 1861 the school began to receive public attention, and obtained some financial support from the Denominational School Board. In 1862 a number of prominent citizens held a meeting, attended by the Governor, Sir Henry Barkly, and representatives of all the principal Protestant denominations, to form a committee to establish an institution, to be called the Victorian Deaf and Dumb Institution, whose aim was to provide a home and instruction for the deaf and dumb. In the meantime, as the numbers of pupils increased, Rose's school moved in 1861 to larger premises in Henry Street, Windsor, then in 1862 to a former hotel in Henry Street, and in 1864 to Commercial Road. In 1863 the Government granted ₤250 to the school, and the Committee decided to ask for a grant of land for a new building, with sufficient space also for recreation and a garden. Between 1864 and 1867, most of the land between St Kilda Road, Punt Road, High Street and Commercial Road was granted to five large benevolent or community institutions: the Victorian Deaf and Dumb Institution, the Victorian Asylum and School for the Blind, Wesley College, the Alfred Hospital, and the Freemasons' Alms Houses. The site allocated to the Deaf and Dumb Institute was six acres; a one acre block at the rear was later purchased from the Presbyterian Church [Burchett, Utmost for the Highest, p11).

HISTORY OF PLACE

With the backing of its committee, made up of prominent and influential citizens (the Governor Sir Henry Barkly was the first President, Sir William Stawell then acted as President for thirty years, and Edward Henty was an early Vice-president), meetings were held to raise money for a building fund. ₤1654 was raised, and a grant of ₤3000 was received from the Government. The architects Crouch and Wilson were instructed to draw up plans, but Burchett notes that Rose 'had a design ready', and that 'it was upon this design that the architects drew up the final plans' [Burchett, Utmost for the Highest, p 110]. The building contract was signed on 4 January 1866; Mr Ireland was the contractor. The foundation stone was laid on 6 March 1866 by the Governor Sir C H Darling, and the building was opened on 13 October 1866 by His Excellency Sir J H T Manners-Sutton. The building provided both classrooms and residential accommodation. Rose was appointed the first Superintendent and his wife the first matron.

The design chosen was for an impressive symmetrical Gothic Revival style building, of a sort closely associated with educational institutions during the nineteenth century. The Crouch and Wilson drawings are on display in the building, and there are many early photos. Only the two storey southern wing and the central three storey block with the tower were built initially, the final cost for this section, including furniture and fittings, being ₤7266/18/6. The grounds of the new building were enhanced by several gifts during the 1860s of plants, shrubs and seeds from Baron von Mueller, director of the Melbourne Botanic Gardens. In 1868 Rose presented to the school the marble fountain and pond now in the front garden. By 1871 seventy five children were enrolled, and the Committee decided to build the north wing. A tender for ₤5120 from H Lockington was accepted, and the building was completed in October 1871.

The Institution was highly regarded, and attempted to keep up with international developments in the education of the deaf. At first the manual method, which Rose had learned in England, were used, but in 1879 oral methods were introduced, the first time these had been used in Australia (Vision and Realisation, v 3, p 433). The activities in which the children were engaged were the usual educational training (reading writing, arithmetic, etc), religious instruction, sport and physical education, and vocational training to fit them for life after school. Boys were taught trades such as boot-making, woodwork and gardening, and the girls were taught dressmaking and cooking (and later office skills). In 1875 it was reported that sixty eight students had left the school and that with few exceptions they were self-supporting. Former teachers from the school later became principals at schools for the deaf in South Australia, West Australia, Queensland and Tasmania. In 1882 Rose was succeeded by S Johnson as Superintendent, W D Cook followed in 1885, J H Burchett in 1926 and A R Cook in 1949 (Vision and Realisation, v3, p 434).

Various additions to the Institution were made over the years. In the 1880s, following several cases of severe illness it was decided to build a hospital in the front garden north-west of the school, at a cost of ₤660 plus ₤70 for fittings. This was later used as extra accommodation for the State School, and was known as the Garden School, but was sold and removed in 1927 to make way for the new school building. An extension to the north of the north wing, shown on the Crouch & Wilson plans, appears on a SLV photo c1885-7, and on the 1896 MMBW plan. This was later extended further to the north in the same style and materials, probably in the early twentieth century. The detached gymnasium in the boys' playground shown in the original Crouch & Wilson plans was built in 1890. In about 1905 there were additions and alterations to improve school and dormitory accommodation. The extension to the south of the south wing for a chapel (later used as a gymnasium) in the style of the original building is not shown on 1896 MMBW plan, so was built after that date, possibly in c1905.

Boys and girls were strictly segregated until well into the twentieth century. Separate boys' and girls' playgrounds are marked on Crouch & Wilson drawings and on the MMBW plan, the girls' to the north of the site, the boys' to the south along High Street. There was a tennis court in the front garden, used by staff and pupils, which was asphalted in 1906.

The 1890 the Education Act gave the Government the power to establish State special schools, and in 1912 an addition gave it the power to establish schools for the feeble-minded, the deaf, the dumb and the blind. In 1913 the School for the Deaf and Dumb became State School number 3774. The committee continued to manage the residential accommodation and the affairs of the Institute (Burchett, p 141). The new school, a single storey stuccoed building of three wings in a U-shape around a courtyard, designed by PWD architect Edwin Evan Smith, was built in the front garden in 1928.

In 1942 the institute was taken over by the RAAF, and the school moved to Marysville for two years, returning at the beginning of 1944, though the RAAF didn't leave until later in the year.

A brick trade block, incorporating woodwork and metalwork rooms, was built in c1940 at the south-east corner of the main building along High Street.

The rubella epidemic of 1940-41 resulted in increased demand for accommodation, and several additions and new buildings were added in the post-war period: from 1948, extensions built by E A Watts, at the south-east corner of the bluestone building, comprising two new brick wings with dormitories, bathrooms, a small picture theatre (the Fenton Memorial Hall, parallel to the chapel wing, c1950), and craft rooms (c1949), which cost ₤25,000, built with financial assistance from the Gladys Fenton Estate; in c1952 brick extensions designed by Arthur Purnell on the north-east corner of the main building, and a brick second story over part of the single storey bluestone service wing. In the 1990s the brick extension was removed and the second storey addition was rendered; in 1952 brick offices also designed by Arthur Parnell and later used as a shop were added onto the south of the front facade (removed in the 1990s); increased teaching facilities were at first provided by temporary army huts until a second storey, designed by Percy Everett, was added to the west wing of the school in 1953 (Vision and Realisation, v3, p 434). This was removed in the 1990s, restoring the original appearance of the building; the W D Cook Pre-School Centre for Deaf Children on High Street, designed by Arthur Parnell, opened in 1957; in 1960 a new art and craft building, and a common room building were constructed near the tennis court (both now removed); a new administration building to the east of the school building was added in 1971 (now removed); a special need room for seniors near the Pre-School, and a science and graphics room to the south of the 1928 school building were added in 1985 (both now removed).

In the 1990s extensive renovation and conservation works were carried out. Many of the unsympathetic additions dating from the 1950s to1980s were removed. The 1950s second storey on the west wing of the 1928 school was also removed, and the original appearance of the Smith building restored. New single storey school buildings were added to the east of this, one part filling in the fourth side of the courtyard of the 1928 school, and a new building was added between this and the north wing of the old building, with a covered walkway connecting this to the old school. Single storey school buildings were also added at the rear of the site in the 1990s.

In 1949 the name changed from the Victorian Deaf and Dumb Institution to the Victorian School for Deaf Children, reflecting changing attitudes to the deaf. Until 1948 this school alone cared for deaf children in Victoria. In 1951 enrolment reached its all time high of 236 (approximately half of whom were day students), but as other schools for the deaf opened, and with technological advances in the treatment of deafness (especially the development of the bionic ear) the number of pupils has gradually decreased. The attendance in 2007 is about sixty. The name is now Deaf Children Australia (since c2003).

DEAF CHILDREN AUSTRALIA (FORMER VICTORIAN DEAF AND DUMB INSTITUTION) - Plaque Citation

Designed by Crouch & Wilson, this Gothic Revival school was built in 1866 to provide a home, education and vocational training for deaf and dumb children, the first such major institution in Australia.

DEAF CHILDREN AUSTRALIA (FORMER VICTORIAN DEAF AND DUMB INSTITUTION) - Permit Exemptions

General Exemptions:General exemptions apply to all places and objects included in the Victorian Heritage Register (VHR). General exemptions have been designed to allow everyday activities, maintenance and changes to your property, which don’t harm its cultural heritage significance, to proceed without the need to obtain approvals under the Heritage Act 2017.Places of worship: In some circumstances, you can alter a place of worship to accommodate religious practices without a permit, but you must notify the Executive Director of Heritage Victoria before you start the works or activities at least 20 business days before the works or activities are to commence.Subdivision/consolidation: Permit exemptions exist for some subdivisions and consolidations. If the subdivision or consolidation is in accordance with a planning permit granted under Part 4 of the Planning and Environment Act 1987 and the application for the planning permit was referred to the Executive Director of Heritage Victoria as a determining referral authority, a permit is not required.Specific exemptions may also apply to your registered place or object. If applicable, these are listed below. Specific exemptions are tailored to the conservation and management needs of an individual registered place or object and set out works and activities that are exempt from the requirements of a permit. Specific exemptions prevail if they conflict with general exemptions. Find out more about heritage permit exemptions here.Specific Exemptions:General Conditions: 1. All exempted alterations are to be planned and carried out in a manner which prevents damage to the fabric of the registered place or object. General Conditions: 2. Should it become apparent during further inspection or the carrying out of works that original or previously hidden or inaccessible details of the place or object are revealed which relate to the significance of the place or object, then the exemption covering such works shall cease and Heritage Victoria shall be notified as soon as possible. Note: All archaeological places have the potential to contain significant sub-surface artefacts and other remains. In most cases it will be necessary to obtain approval from the Executive Director, Heritage Victoria before the undertaking any works that have a significant sub-surface component. General Conditions: 3. If there is a conservation policy and plan endorsed by the Executive Director, all works shall be in accordance with it. Note: The existence of a Conservation Management Plan or a Heritage Action Plan endorsed by the Executive Director, Heritage Victoria provides guidance for the management of the heritage values associated with the site. It may not be necessary to obtain a heritage permit for certain works specified in the management plan. General Conditions: 4. Nothing in this determination prevents the Executive Director from amending or rescinding all or any of the permit exemptions. General Conditions: 5. Nothing in this determination exempts owners or their agents from the responsibility to seek relevant planning or building permits from the responsible authorities where applicable. Minor Works : Note: Any Minor Works that in the opinion of the Executive Director will not adversely affect the heritage significance of the place may be exempt from the permit requirements of the Heritage Act. A person proposing to undertake minor works may submit a proposal to the Executive Director. If the Executive Director is satisfied that the proposed works will not adversely affect the heritage values of the site, the applicant may be exempted from the requirement to obtain a heritage permit. If an applicant is uncertain whether a heritage permit is required, it is recommended that the permits co-ordinator be contacted.DEAF CHILDREN AUSTRALIA (FORMER VICTORIAN DEAF AND DUMB INSTITUTION) - Permit Exemption Policy

The purpose of the Permit Policy is to assist when considering or making decisions regarding works to the place. It is recommended that any proposed works be discussed with an officer of Heritage Victoria prior to them being undertaken or a permit is applied for. Discussing any proposed works will assist in answering any questions the owner may have and aid any decisions regarding works to the place. It is recommended that a Conservation Management Plan is undertaken to assist with the future management of the cultural significance of the place. The valuable work already completed by David Prest could form the basis for this.

Internal works to non-registered buildings are exempt from permit requirements. Additions to non-registered buildings and addition of new buildings to the site may impact upon the cultural heritage significance of the place. Non-registered buildings on the site remain part of the heritage place and permit applications will be required for additions and demolitions.The purpose of this requirement is not to prevent any further development on this site, but to enable control of possible adverse impacts on heritage significance during that process.

The significance of the place lies in its rarity and intactness as a nineteenth century Gothic Revival educational institution with twentieth century additions, which has been in continuous use to the present day. The significance also lies in the siting of the main building and the views obtained from St Kilda Road. All the registered buildings, structures and objects are integral to the significance of the place and any alterations that impact on their significance are subject to permit application.

The extent of registration protects the whole site and in particular the main building, the Rose fountain, the 1928 school building, the former trade block, the W D Cook Pre-School Centre, the entrance gateposts, the main drive and flanking avenue of trees, the mature trees in the front garden and the camphor laurel tree in the rear courtyard. While the Pre-school demonstrates part of the history of the development of the school, it has no particular architectural significance. Important features of the interior of the main building which must be conserved include the boys' bath in the basement, original tiling in the ground floor bathrooms, remains of the original decorative scheme in the reception area and a dumb waiter in the laundry.

The main building contains a collection objects, furniture, photographs, architectural plans and other archival material which has not been recorded in an inventory. It is desirable that an inventory is undertaken and a Conservation Management Policy prepared for this collection.

Although the landscape items have not been itemised in detail they are considered to be included in the registration as part of the registered land. Permit applications will be required for alterations to any of these elements, apart from a range of minor and maintenance works covered by the exemptions. The main building is particularly suited to institutional/public use and should be allowed to be modified to maintain this use. The imposing visual presentation of the building to St Kilda Road is an important aspect of the original design which should be respected. The angled gateway, the tree-lined entrance driveway and the circular drive in front of the entrance to the main building are significant elements which should not be altered.

-

-

-

-

-

MAJELLA

Victorian Heritage Register H0783

Victorian Heritage Register H0783 -

PRAHRAN TOWN HALL

Victorian Heritage Register H0203

Victorian Heritage Register H0203 -

FORMER POLICE STATION AND COURT HOUSE

Victorian Heritage Register H0542

Victorian Heritage Register H0542

-

'The Pines' Scout Camp

Hobsons Bay City

Hobsons Bay City -

106 Nicholson Street

Yarra City

Yarra City -

12 Gore Street

Yarra City

Yarra City

-

-