Back to search results

HARRY JOHNS COLLECTION

MUSEUMS VICTORIA, 11 NICHOLSON CARLTON, AND AUSTRALIAN SPORTS MUSEUM, MELBOURNE CRICKET GROUND, BRUNTON AVENUE EAST MELBOURNE, MELBOURNE CITY

HARRY JOHNS COLLECTION

MUSEUMS VICTORIA, 11 NICHOLSON CARLTON, AND AUSTRALIAN SPORTS MUSEUM, MELBOURNE CRICKET GROUND, BRUNTON AVENUE EAST MELBOURNE, MELBOURNE CITY

All information on this page is maintained by Heritage Victoria.

Click below for their website and contact details.

Victorian Heritage Register

-

Add to tour

You must log in to do that.

-

Share

-

Shortlist place

You must log in to do that.

- Download report

image001

On this page:

Statement of Significance

The Harry Johns Collection is located on Wurundjeri Country.

What is significant?

The Harry Johns Collection being 85 objects including a truck related to the Harry Johns Boxing Troupe, held at Museums Victoria and the Australian Sports Museum.

How is it significant?

The Harry Johns Collection is of historical significance to the State of Victoria. It satisfies the following criterion for inclusion in the Victorian Heritage Register:

Criterion A

Importance to the course, or pattern, of Victoria’s cultural history.

Criterion B

Possession of uncommon, rare or endangered aspects of Victoria’s cultural history.

Why is it significant?

The Harry Johns Collection is historically significant for its association with tent boxing in Victoria. Tent boxing was a popular entertainment at agricultural shows in the early to mid-twentieth century, and troupes travelled in trucks around Victoria and the eastern coast with their tents and equipment. Tent boxing was a working-class pursuit and around half the Harry Johns boxers were Aboriginal men. For Aboriginal fighters, boxing opened opportunities for employment, success and public acclaim at a time of profound discrimination. Aboriginal boxers became heroes in their communities, and many took up positions of political and cultural leadership later in life. The collection provides insight into the history and organization of tent boxing in Victoria and its place in working class, rural and Aboriginal life.

(Criterion A)

The Harry Johns Collection is rare, being one of a small number of heritage places or collections remaining that demonstrates the history of tent boxing in Victoria.

(Criterion B)

Show more

Show less

-

-

HARRY JOHNS COLLECTION - History

Tent boxing

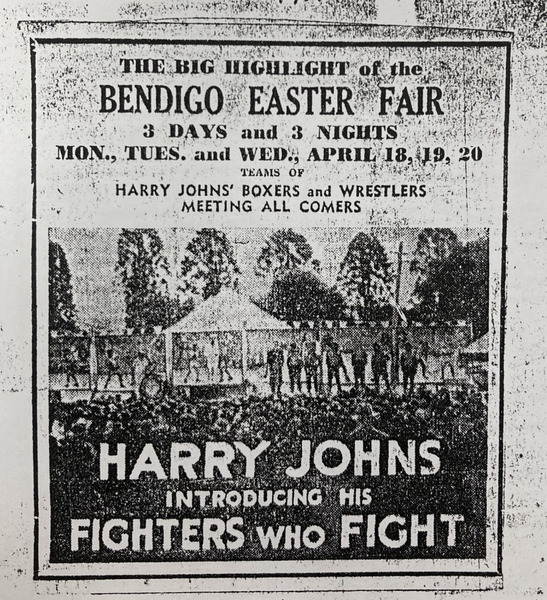

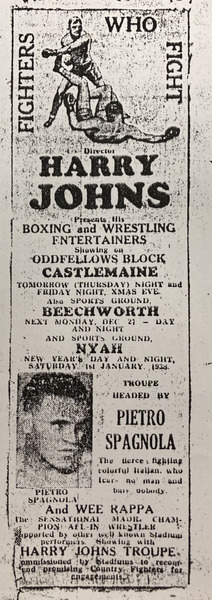

Tent boxing has a long history in British culture and was evident in the Victorian colony from at least the 1860s. From around the late nineteenth century, travelling boxing troupes were a familiar sight at agricultural shows in Australia. Previously bare-knuckle boxing had been popular albeit illegal. The adoption of the Queensberry Rules in the 1880s saw boxing legislation and gloved contests, which opened new opportunities for boxers and promoters. Travelling troupes, such as those run by Harry Johns and Jimmy Sharman, became an important part of the Australian boxing story. They followed the annual calendar of agricultural shows, carnivals, and rodeos travelling from southern Australia in the summer to northern Queensland in the winter. Jimmy Sharman’s troupe was based in NSW (though had an office in Melbourne) while the Harry Johns Boxing Troupe was based in Victoria.Tent boxing was a theatrical event in an era before television and the broadcasting of sporting events. The action began before the boxing started. Colourful tents, the boom of the drum, the brilliance of the banners promised excitement and drew in the crowds. Local amateurs were encouraged to match their skills in the ring against troupe fighters. Promoters worked the crowd and spruiked challenges to local boxers: ‘Who'll take a glove? What about coming inside? Bowl my man over in three rounds and I'll give you a fiver!’[1] For spectators, tent boxing thrived on the rivalry of opposites: the out-of-town troupe man versus the local man, and black versus white. In 1937 an advertisement for the Harry Johns Troupe included references to ‘WEE RAPPA the SENSATIONAL MAORI CHAMPION’ and ‘PIETRO SPAGNOLA: The fierce fighting colourful Italian’.[2] Aboriginal fighters comprised around half the members of travelling boxing troupes, including the Harry Johns troupe, and were central to their success.[3]

Harry Johns Boxing Troupe

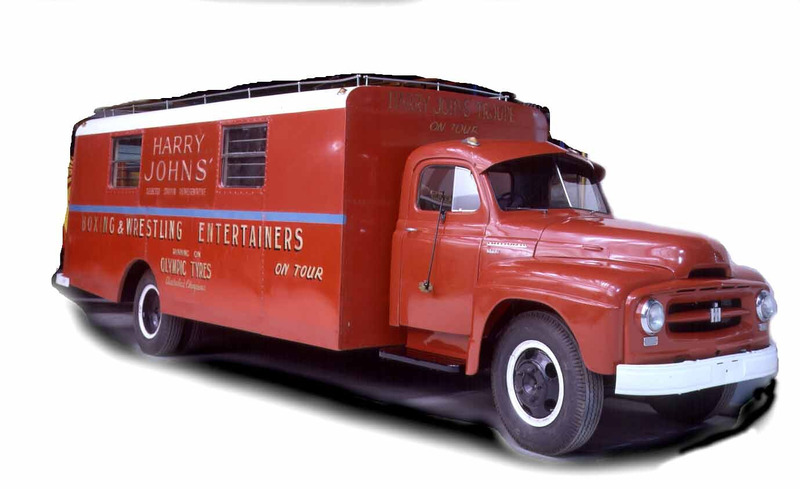

Harry Johns was born c.1880 and entered the Australian boxing circuit around 1914. By 1915 he had become a well-known boxer and featherweight of Bendigo. Following his retirement in 1918, Johns became a boxing trainer and manager at the Fitzroy Athletic Club, ‘where he imparted his knowledge to a great number of youngsters’.[4] In 1928 he launched the famous ‘Harry Johns Boxing Troupe’, which toured the show circuit in the eastern states of Australia until the 1960s. In Melbourne some fights took place at the Melbourne Stadium in West Melbourne (replaced by Festival Hall) and at the Fitzroy Stadium on the northeast corner of St David and Brunswick streets, Fitzroy (now demolished).[5]In 1934 Johns’ troupe was described as a team of around twenty fighters which undertook extensive travelling in a caravan ‘which is a good-sized motor van, carrying the team and a collapsible trailer for the gear… Every year South Australia, Victoria, Tasmania and New South Wales, right to the Queensland border, are covered’.[6] In 1954 Johns purchased a new cabin and chassis from the International AR 160 Series and attached the rear section from his previous truck onto it.[7] Johns arranged for the Olympic Tyre company to pay for the painting and signwriting on this long vehicle in exchange for advertising their brand. Like other boxing entrepreneurs, Harry Johns possessed business acumen and a flair for showmanship and visual communication. During busy times of the year, he was managing two or three troupes under his name.[8]Aboriginal tent boxers

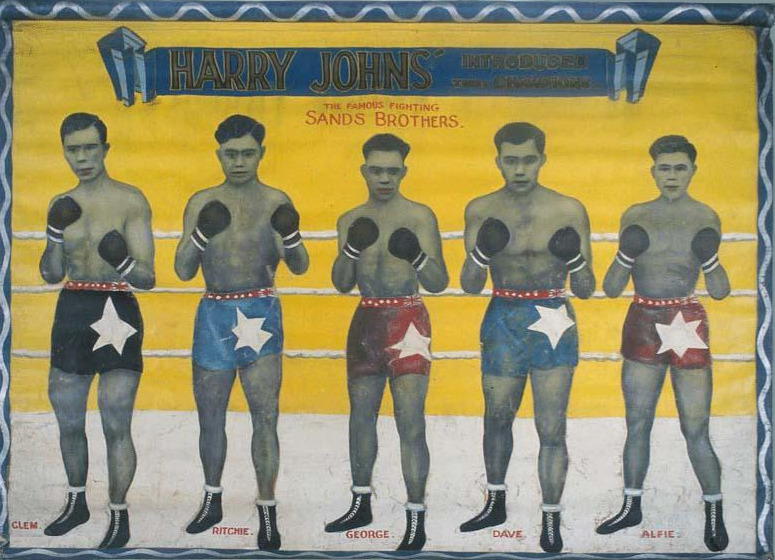

Boxing was an important aspect of Aboriginal culture in the twentieth century. Former fighter Alick Jackomos recalled ‘If you were looking for Aboriginal people at the show grounds you went to the boxing troupe and nine time out of ten, you’d find them there’.[9] Doug Nicholls, later an Aboriginal leader, pastor and Governor of South Australia, signed on with Jimmy Sharman for three years in 1931. The Ritchie brothers from Kempsey fought under the name of ‘The Famous Fighting Sands Brothers’ with Harry Johns, and also with Jimmy Sharman. At Warrnambool in the 1940s, the Aboriginal families from Framlingham all contributed fighters to boxing tents at the show, including members of the Roach, Alberts, Couzens, Clarke and Austin families. Henry ‘Banjo Clarke’, a Framlingham elder, joined Harry Johns’ troupe in the 1930s when he was living in Kerr Street, Fitzroy down from the Johns family.[10]Like other promoters, Harry Johns recruited Aboriginal men. For example, in 2010 Ted Lovett a Gunditjmara-/Djabwurrung man, recalled: ‘Well, I can remember when I was about 14 or 15 and I remember Harry Johns coming into the Royal Hotel one day and he was looking for fighters… and to take one of us up to Ferntree Gully… there was a showing up there and he came and got me and a couple of other blokes that were there’.[11]A lot of Aboriginal fighters camped at the back of Johns’ house at 38 Kerr Street, Fitzroy ‘because they came down from the country towns and didn’t have homes in Melbourne … so they stayed at the back there with their swags in the shed’.[12] Banjo Clark recalled ‘I started with Harry Johns troupe when I was fifteen. If you can use your dukes you just go, and they test you out in a big shed in the yard. If you can fight a bit, they say, ‘Righto you’ll do’. Or Johns’ would say to someone, ‘Learn a bit more sense so you will be able to join me’. And he would put them on to some of the good men and into it. This was his backyard in Melbourne’.[13].Tent boxing was infused with a complex mix of race politics. The sport offered young Aboriginal men the chance to travel, to meet other Aboriginal and white Australians, make friends, and to experience the capital cities. It provided an escape from missions, and potentially saw them earn more than as a labourer or factory worker: ‘The better the fighter was, the more money could be made. Tent fighting became a very significant part of mission life – a very important money earner. It kept whole communities of families living with adequate food supplies and clothing’.[14] Aboriginal boxer Eric Clarke from Framlingham recalled that in the 1930s spruikers or ‘geemen’ would stir up the crowd by calling out statements like ‘Who wants to fight the darkie?’[15] Racial stereotypes also informed the promotion and experiences of international fighters of colour.The tent theatre allowed Aboriginal men to challenge dominant racial discourses. One boxer remarked: 'I felt good when I knocked white blokes out. I felt good. I knew I was boss in the boxing ring'.[16] Tent boxing played a role in supporting Aboriginal fighters to achieve employment, success and acclaim at a time of profound discrimination. Fighters became heroes within their communities, who turned out to see them on the line-up board and claim a connection to them. For some it became an entry into professional boxing as well as inspiring family members. Lionel Rose’s father Ron Rose, a Gunditjmara man, fought with Harry Johns. Lionel Rose became an Australian sporting hero, was awarded an MBE and was Australian of the Year in 1968. Some participants in tent boxing took up positions of political and cultural leadership later in their lives. In October 2022, Rodney Carter, a Dja Dja Wurrung and Yorta Yorta man, reflected on the meaning of tent boxing in Aboriginal communities:Tent Boxing, as did many competitive sports, allowed a moment of sameness or even equality to compete on Country as family whereas many of the Ancestors before could not. It is known to the competitor of the historical discrimination as First Nations people of the individual, family, and community that many of their inherent rights now better understood today were not acknowledged. You now enter this place of competition to not just compete as a sportsperson but show others and evidence that your race is valuable and have been able to tolerate many injustices and still have an exceptional honour to the rules of that competition. You have at the least in your participation represented with the weight of the world upon you, our people with honour.[17]Australian Screen (National Film and Sound Archive) hold historical video footage of tent boxing and Aboriginal people talking about their experiences in the sport and its meaning for them and their communities:The Harry Johns Collection

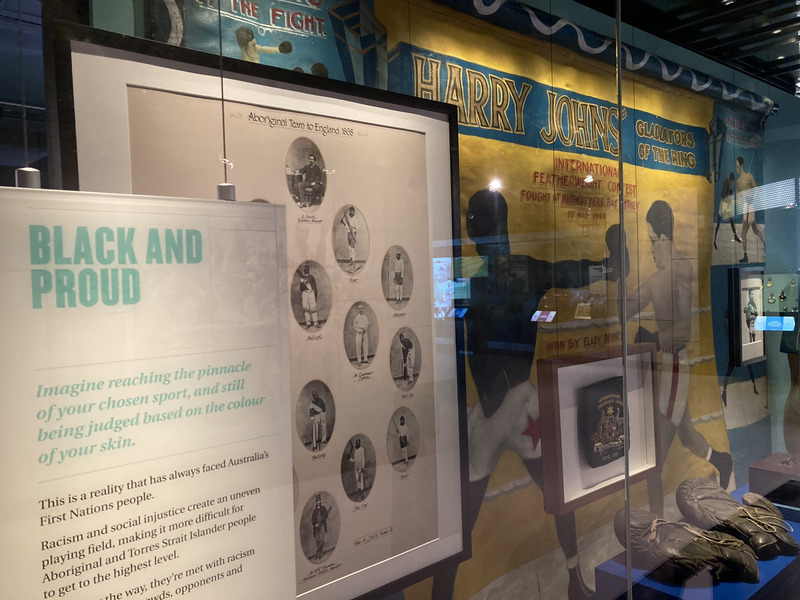

From around the 1950s Harry Johns’ daughter Francesca Rose accompanied him and helped manage the troupe. In 1960 Harry Johns ceased active involvement after experiencing a stroke and died seven years later. The red truck sat in Francesca’s backyard for more than 30 years. In 1996 the Johns’ children, Francesca, Ernie and Harry junior, donated the truck to Museums Victoria along with the original equipment inside it, including a tent, trestle tables, loudspeakers, spotlight, tickets and clothing.[18]In 1989 the family had already donated objects related to the Harry Johns Boxing Troupe to the Australian Gallery of Sport and Olympic Museum including banners, boxing shoes and the drum. The truck was on display on the ground floor of Melbourne Museum from 2000 to 2020. It was accompanied by a text providing the history. During that time, it became part of the Treasures of the Museum exhibition. Items from the Harry Johns Collection are currently (2022) on display in the ‘Black and Proud’ exhibit at the Australian Sports Museum.

Tent boxing in song and film

The contemporary significance of the tradition of tent boxing in Aboriginal families and communities is reflected in the release by Archie Roach in 2019 of a song called ‘Rally ‘round the drum’:

Rally ‘round the drum (by Archie Roach)

Excerpts:

Like my brother before me

I'm a tent boxing man

Like our daddy before us

Travelling all around Gippsland

I woke up one cold morning

Many miles from Fitzroy

And slowly it came dawning

By Billy Leach I was employed

Rally ‘round the drum boys

Rally ‘round the drum

Every day, and every night boys

Rally ‘round the drum…

Then Billy starts a-calling

Step right up, step right up, step right up one and all

Is there anybody game here?

To take on Kid Snowball

Rally 'round the drum boys

Rally 'round the drum

Is there anybody game here?

Rally 'round the drum

Non-Aboriginal musicians have also explored tent boxing in their lyrics including Midnight Oil’s ‘Jimmy Sharman’s Boxers’ (1984) and Cold Chisel’s song ‘Yesterdays’ (1994). The film ‘September’ by Peter Carstairs and John Poulson (2007), which explores the importance of boxing to Aboriginal communities, was screened at a number of international film festivals.Selected bibliographyBroome, Richard, 'Theatres of Power: Tent Boxing Circa 1910-1970', Aboriginal History, Vol. 20, 1996, pp. 1-23.

Broome, Richard with Alick Jackomos Sideshow Alley, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1998.

Eric Clarke, The Blood and Sweatdrenched Canvas: A Social History of the Survival of Aboriginal Tent Fighters During the Depression and Postwar Era in Western Victoria, Thesis, School of Education College of Design and Social Context, RMIT University, April 2010, p. 22.

‘Harry Johns Boxing Troupe Collection’ https://collections.museumsvictoria.com.au/articles/2018 [accessed 21 October 2022]

Longo, Enrica ‘Boxers of history in truckloads’ Age, 10 July 1997, Metro Section, p. C3.

Message Stick Video Clips, ‘Tent Boxers’ 2001, https://aso.gov.au/titles/tv/message-stick-tent-boxers/ [accessed 24 October 2022]

Museums Victoria, Harry Johns Collection Research File.

NITV, ‘A round or two for a pound or two: The touring tent boxing circuses’, 3 February 2017, https://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/article/a-round-or-two-for-a-pound-or-two-the-touring-tent-boxing-circuses/k2itfbm1n [accessed 24 October 2022]

Footnotes

[1] 'Boxing Showmen', Argus 18 Apr 1936, p.8 quoted in Broome, ‘Theatres of Power’ pp. 14-15.

[2] ‘Harry Johns: Fighters Who Fight’, Sporting Globe, 22 December 1937, newscutting in Harry Johns Collection, Museums Victoria.

[3] Broome, Sideshow Alley, p. 178.

[4] ‘Harry Johns wooed to the boxing game’, Sporting Globe, 1934, newscutting in Harry Johns Collection, Museums Victoria.

[5] From 1939 a place called the Fitzroy Stadium was located at the former Lyric Theatre at 261 Johnston Street Fitzroy.

[6] ‘Started as a boy: Harry Johns as Showman’, Sporting Globe, 8 August 1934, newscutting in Harry Johns Collection, Museums Victoria.

[7] ‘Harry Johns Boxing Troupe Collection’ https://collections.museumsvictoria.com.au/articles/2018 [accessed 21 October 2022]

[8] ‘Started as a boy: Harry Johns as Showman’, Sporting Globe, 8 August 1934, news-cutting in Harry Johns Collection, Museums Victoria.

[9] Broome, Sideshow Alley, p. 172.

[10] Museum Victoria Research File, Boxing Truck Research, RF2270.

[11] Ted Lovett (2010) quoted in Eric Clarke, The Blood and Sweatdrenched Canvas: A Social History of the Survival of Aboriginal Tent Fighters During the Depression and Postwar Era in Western Victoria, Masters Thesis, School of Education College of Design and Social Context, RMIT University, April 2010, p. 25.

[12] Remembering Aboriginal Fitzroy: An interview with Alick Jackomos, Aboriginal Affairs Victoria 1998, p.41.

[13] Broome, Sideshow Alley, p.173-174.

[14] Eric Clarke, The Blood and Sweatdrenched Canvas, p.26.

[15] Eric Clarke, The Blood and Sweatdrenched Canvas, p.22.

[16] Queenslander Henry Collins quoted in Broome, ‘Theatres of Power’, p. 21.

[17] Correspondence from Rodney Carter to Heritage Victoria, 26 October 2022.

[18] Enrica Longo, ‘Boxers of history in truckloads’ Age, 10 July 1997, Metro Section, p. C3.HARRY JOHNS COLLECTION - Assessment Against Criteria

Criterion

The Harry Johns Collection is of historical significance to the State of Victoria. It satisfies the following criterion for inclusion in the Victorian Heritage Register:

Criterion A

Importance to the course, or pattern, of Victoria’s cultural history.Criterion B

Possession of uncommon, rare or endangered aspects of Victoria’s cultural history.HARRY JOHNS COLLECTION - Permit Exemptions

General Exemptions:General exemptions apply to all places and objects included in the Victorian Heritage Register (VHR). General exemptions have been designed to allow everyday activities, maintenance and changes to your property, which don’t harm its cultural heritage significance, to proceed without the need to obtain approvals under the Heritage Act 2017.Places of worship: In some circumstances, you can alter a place of worship to accommodate religious practices without a permit, but you must notify the Executive Director of Heritage Victoria before you start the works or activities at least 20 business days before the works or activities are to commence.Subdivision/consolidation: Permit exemptions exist for some subdivisions and consolidations. If the subdivision or consolidation is in accordance with a planning permit granted under Part 4 of the Planning and Environment Act 1987 and the application for the planning permit was referred to the Executive Director of Heritage Victoria as a determining referral authority, a permit is not required.Specific exemptions may also apply to your registered place or object. If applicable, these are listed below. Specific exemptions are tailored to the conservation and management needs of an individual registered place or object and set out works and activities that are exempt from the requirements of a permit. Specific exemptions prevail if they conflict with general exemptions. Find out more about heritage permit exemptions here.Specific Exemptions:The following proposed permit exemptions are for works and activities not considered to cause harm to the cultural heritage significance of the Harry Johns Collection.

All of the following exemptions must be in accordance with the National Standards for Australian Museums and Galleries and/or in accordance with the accepted collection management standards, policies and procedures of Museums Victoria and the Australian Sports Museum.· Management of items (including removal and relocation, display, conservation, and temporary loans of eighteen months or less).· The conservation, research or analysis of items does not require approval by the Executive Director pursuant to the Act, where the custodian employs qualified conservators.

-

-

-

-

-

ROSAVILLE

Victorian Heritage Register H0408

Victorian Heritage Register H0408 -

MEDLEY HALL

Victorian Heritage Register H0409

Victorian Heritage Register H0409 -

DRUMMOND TERRACE

Victorian Heritage Register H0872

Victorian Heritage Register H0872

-

1) ST. ANDREWS HOTEL AND 2) CANARY ISLAND PALM TREE

Nillumbik Shire

Nillumbik Shire

-

-