MURNDAL

1356 MURNDAL ROAD TAHARA, SOUTHERN GRAMPIANS SHIRE

-

Add to tour

You must log in to do that.

-

Share

-

Shortlist place

You must log in to do that.

- Download report

Statement of Significance

What is significant?

Murndal is at the heart of a pastoral run formerly known as Spring Valley, which was initially part of a larger squatting run called Tahara. Tahara was held in the 1840s under two licences by brothers Samuel Pratt Winter and George Winter, members of a Protestant Irish-English Ascendancy family which owned large estates in Ireland.

The Tahara run was split in 1845, and the eastern part, known as Spring Valley and later as Murndal, was managed until 1849 by Thomas Murphy whilst Samuel Winter attended to his interests in Van Diemen's Land. During this time the original two roomed stone cottage was built, and this still survives as the library at the heart of the homestead. The book collection begun by Winter in the 1840s forms the core of this library.

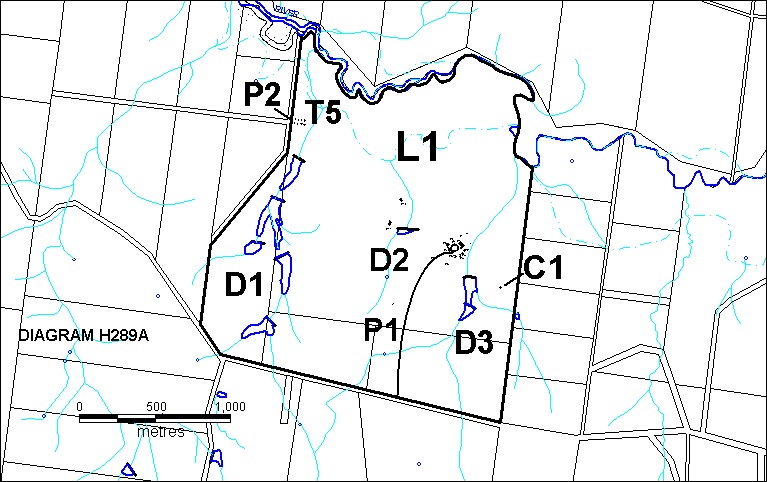

The pre-emptive right to Spring Valley acquired by Winter in 1854 included one mile of frontage to the River Wannon. The Selection Acts saw some of Winter's run sold off, but by 1870 he had managed to secure freehold to about 14,000 acres.

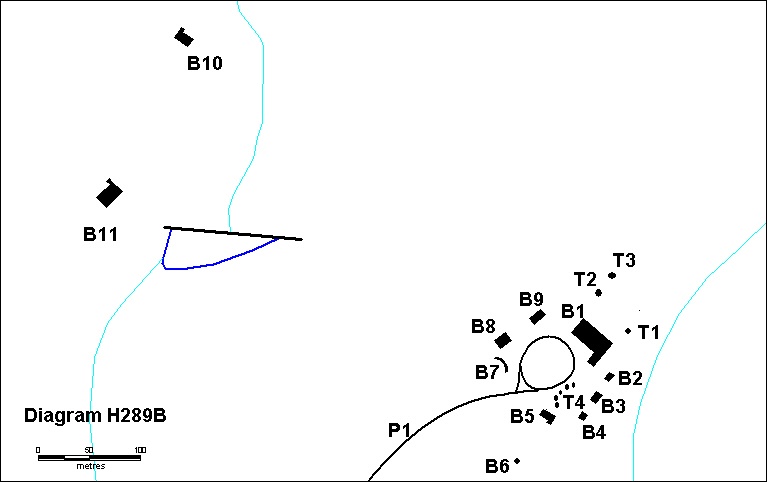

With the securing of a freehold title, Winter was more confident of carrying out capital improvements. The homestead was increased in size firstly by the bluestone west wing and verandahs added to the original cottage in 1856, and then in 1875 by the substantial two storey bluestone east wing incorporating the dining room. A variety of timber outbuildings were added, few of which have survived, but an important collection of mostly brick or stone buildings remain at the back of the house. These include a two storey bluestone coolroom, and a men's hut, carpenter's shop and laundry all built of bricks made on the station. The largest buildings in this group are an elevated timber barn and a two storey brick stables which was designed in a Colonial Georgian style. About one kilometre from the house is the shearing shed, of timber and corrugated iron, and possibly dating to the 1860s. Nearby is the manager's house, the earliest part of which is constructed from bluestone probably in the 1850s, with later weatherboard additions.

Samuel Pratt Winter created at Murndal a deliberate evocation of the eighteenth century English and Irish landscapes with which he was familiar. The sparsely wooded and undulating landscape was enhanced in the manner of English landscapes by the creation of a series of lakes, with the valley of the meandering River Wannon providing a picturesque setting. The remnants of a boating shed illustrate how the lakes served both a recreational and irrigation function.

Much of the landscaping and large scale planting of predominantly European trees was completed by about 1870. There was an extensive planting of deciduous trees; elms, oaks and Osage orange, and a few evergreen trees; Holm oak and pines in large stands and rows. Vistas were created from the house down to the river. An avenue of oaks marked the crowning of successive British monarchs, and was a further evocation of the Old World landscape.

A large English Oak in the homestead garden known as the Cowthorp Oak was planted in 1886. It was from a seedling of the famous Cowthorp Oak in Yorkshire, mentioned in the Doomsday Book and regarded as the world's oldest English Oak. A rare Palestine Oak, Quercus calliprinos, was planted in 1916 from acorns collected by Captain William L Winter-Cooke at Gallipoli.

The family cemetery was created in 1878 on a small knoll overlooking the south of the house. A hawthorn hedge encloses the site, which is also planted with King pines.

When Samuel Winter Cooke inherited this successful pastoral station from his uncle in 1878 he continued the Old World traditions of Ascendancy Ireland. The addition of further buildings around the homestead reinforced the village atmosphere. Winter Cooke fostered the sense of community, allowing the use of the dining room at Murndal as the setting for religious services for station workers until he provided land and funds in 1881 for the building of St Peter's Anglican Church at Tahara.

In 1906 the last substantial additions were made to the homestead with a second storey designed by architects Ussher and Kemp in a half-timbered Tudor revival style. Internally, rooms and passageways are richly decorated with silky oak panelling, jarrah and kauri pine floors and carved oak ornamentation to ceilings. Most of the work was executed by the station carpenter, Patrick Aylmer.

How is it significant?

Murndal is of historic, aesthetic and architectural significance to the State of Victoria.

Why is it significant?

Murndal homestead and its surrounding landscape are historically significant for clearly demonstrating characteristic patterns of early land settlement and large-scale pastoral enterprise in Victoria. Through the occupation and ownership of one family, the acquisition and improvement of a pastoral run from the earliest years of squatting in Victoria can be shown. The attainment of a government lease, purchase of the pre-emptive right and gradual accumulation of freehold interest in large parts of the original run through the Selection Acts of the 1860s and 1870s is clearly demonstrated. The different phases of construction of the house demonstrate changes in circumstances of a successful pastoral station. The retention of the original stone cottage beneath later stages of construction demonstrates the desire for continuity, permanence and tradition. The landscape features still clearly demonstrate old boundaries to the squatting run and pre-emptive right.

The library collection at Murndal is historically significant for its integrity, and for its several rare and important volumes. It is unusual for a family library begun in the earliest period of settlement in Victoria to survive intact.

The tree planting at Murndal is of historic significance for its commemorative plantings. The avenue planting of a pair of oaks in 1901, 1910, (both Quercus robur) 1937 (Quercus canariensis) and 1952 (Quercus robur) to mark the coronation of each British monarch since Queen Victoria?s reign is the only example of this type of historical planting in Victoria. The Palestine oak is historically significant, commemorating the family's involvement at Gallipoli, and is a rare example of this species in Victoria.

The lakes and parkland of the Murndal estate are aesthetically significant as a rare example of an improved pastoral landscape on a large scale. It is an evocation of an English landscape, beautified by the creation of lakes and planting of European trees, and based on the eighteenth century principle of art assisting nature. It also demonstrates the sentimentality of successive generations of one family for their Old World origins.

Murndal is architecturally significant for the Arts and Crafts style of the last phase of additions in 1906 which reinforced the ideals of respect for earlier and traditional craftsmanship. The half timber gables, leadlight windows, red tile roof and high quality interior carvings reinforce the sense of authority and permanence by reference to the style of a Tudor manor house at the centre of an English-Irish estate.

See 2008 Site Monitoring Event and initial survey (attachment) for details of the library collection.

-

-

MURNDAL - History

History of Place:

“The grounds at Murndal provide an outstanding setting for a large house, which together with its contents, the various outbuildings and landscape, is possibly Australia’s closest approximation to an English manor and its precincts. The designed landscape is thought to be the largest of its type in Australia and is unknown elsewhere in Victoria.” (Peter Watts, Historic Gardens of Victoria: a reconnaissance from a report of the National Trust of Victoria (Australia), Melbourne 1983 p 113).

At Murndal before 1850 a fenced area around the house contained a grid pattern kitchen garden for vegetables as well as flowers, low clipped hedges and a straight gravel path from the front door to the fence with a willow tree shading the gate. Naturally occurring blackwoods stood in two corners (M L Poulston, The Landscape at Murndal: its origin and development, Master of Landscape Research Report [No institution given]) 1984 p 20).

The garden grew in size and complexity from the 1840s until the 1890s. By the turn of the twentieth century it possessed a variety of elements, including a formal terrace, a retreat garden, a croquet lawn, tennis court and the ‘Wild Garden’ (Poulston op cit p 60). Little of these elements now remains. It is yet to be documented if the Arts & Crafts architect Walter Butler, who oversaw the conversion of the centre of the house to a library in the 1890s, additionally had any design influence on the garden.

Hundreds of acres surrounding the homestead were designed in the landscape traditions of eighteenth century England. The Historic Gardens Study described the landscape as:

“…heavy with nostalgia for Britain with a Coronation Avenue (a new pair of trees is planted for each British coronation), Cowthorp Oak (taken form an acorn of this tree said to be the oldest oak in the world) and Richmond Park (called after its namesake in London). The property abounds with many other associations. Extensive avenues lead out from the homestead and clumps of English trees are placed in prominent positions. A series of large lakes surrounded with exotic trees is located about 1km from the homestead.” (Garden State Committee of Victoria National Trust of Australia (Victoria ), Historic Gardens Study, 1980, Vol II Inventory 2 Category 1).

The naturalistic approach to the landscape came from the English tradition, developed from the eighteenth century, of beautification, and of ideas of art assisting nature. It was in contrast to the formal, axial layouts which had developed hand in hand with Renaissance architecture and planning from the 16th century. The concept of beauty, of creating simple, flowing forms, of unity and harmony became most famously pronounced in the work of Capability Brown in England, for example at Blenheim Palace. (A clear explanation of the development of the naturalistic eighteenth century landscape in England before the advent of the picturesque tradition is given in Tom Williamson’s Polite landscapes: gardens and society in eighteenth-century England, Baltimore 1995).

The use of this tradition at Murndal was an evocation of Britain in the new colony, and the improvements were considered a way of bringing an old world order to the native, unimproved wild landscape. The Australasian in 1910 described it as “art assisting nature and noted that the policy begun at Murndal by Samuel Pratt Winter was being followed by his nephew and successor, Samuel Winter Cooke.” (The Australasian 19 March 1910 p 703)

Much of the landscape around Murndal constitutes the eighteenth century English ideal, with scenes of natural looking clumps of trees in a gently undulating landscape. The serpentine meandering of the Wannon River close to the homestead clearly set the tone for Samuel Pratt Winter’s vision. English trees were planted in prominent positions, on tops of hills and around the artificial lakes, known as the ‘garden dams’(Peter Watts, Historic Gardens of Victoria, p 112). The dams scheme demonstrates an important principle at Murndal: the development of a beautiful landscape by means of the improvements necessary for efficient use of the land (Poulston Op Cit p 30).

In 1857 Winter even constructed a dam on land for which he had applied for gazettal but had not yet secured freehold. It was a move he conceded with injudicious, but nonetheless facilitated cattle grazing (G Forth, The Winters on the Wannon, Warrnambool, 1991 p 138). The dams were probably finished around 1870. Winter noted in his correspondence in 1870 that “The dam over the river I intended to be sufficiently high to allow the overflow over a natural hollow south of the dam into the little gully with the brackish spring.” (SLV Winter-Cooke Collection MS 10840 1.1.15, 13 June 1870). The woolshed dam was designed in 1868 (Poulston op cit p 29). By 1870 Winter had spent more than £1,000 on dam construction (Forth op cit p 138).

Plantings of clumps of trees and thickets provided the ideal cover for pheasants. Pheasants were reared at Murndal for their sport. In 1892 The Australasian reported that sportsmen could get occasional good pheasant shooting, and the numbers of pheasants were getting more numerous under the care of the gamekeeper, ‘old John’. (The Australasian 30 January 1892). At the turn of the century a journalist noted that this was “sport of the real old kind” (Victoria’s Representative Men at Home, facsimile of Punch publication 1904, ed. Michael Cannon, 198?, p 25). In order to thrive, pheasants require a particular landscape. The planting of thickets as cover for pheasants partly dictated the form of the landscape at Murndal.

Such large scale improvements to landscapes as had taken place at Murndal by 1870 required greater security of tenure for squatters than could be established before 1850. Winter only started investing sums of money on fencing and other fixed improvements at Murndal after 1855, when he secured his pre-emptive right to 640 acres around the homestead. (The pastoral run papers for Spring Valley are held in jacket no. 739 at the PRO and at the Lands Department, DNRE). The original two room stone cottage of c1846, designed by Winter himself, (Forth Op Cit p 86) required upgrading once Winter decided to make the Wannon his permanent home.

In April 1856 Thomas Clarke (the station manager) noted in his journal that two of his workers were being employed building walls for the ground floor of an extension to the house (SLV Latrobe Manuscripts Winter-Cooke Collection MS 10840 10.1.1). This was the two storey gabled west wing and extension to the original two room stone cottage, and probably also included the adjacent single storey bluestone block. Photograph (SLV MS 10840 17.6.15, 17.6.16 and 17.6.17 from pre-1875, i.e. before the east wing was built) clearly shows this west wing extension.

It was also noted in Clarke’s journal in April 1856 that the roof of the house was on. Undated photographs of the house (before 1906) clearly show a Morewood and Rogers patent galvanised iron tile roof (e.g. Winter-Cooke Collection SLV MS 10840 17.6.6 and 17.6.10) Tiles found in storage are stencilled ‘Morewood and Rogers Patent’. These tiles became generally available from c1850 to c1860, after which the company changed its name. The verandahs to the original cottage may have been bricked-in at this time, given the survival of the same Morewood & Rogers tiles in this location today. In May 1856 pipes were laid from the spring to the house.

In September 1857 Clarke noted the carpenter being employed on the new men’s hut. In December the hut was shingled. There was a reading room in this building. The Australasian noted in 1892 “An inspection of the quarters for the station hands and the reading room shows that they have not been forgotten in the provision made for general comfort.” (The Australasian 30 June 1892 p 231). The men’s hut comprised two buildings, only one part of which survives today. A single storey stuccoed brick building, with a small belltower, was removed in the 1960s. These demolished buildings are clearly shown in the SLV collection, MS 10840 17.3.4 (c1880) and 17.4.8 (1908).

The 1870 dining room was built with a bow window looking over the garden, and a drawing room above. The cast iron lace verandah was removed c1975 but remains in storage on site. Many photographs of the iron in situ show it painted a light shade, probably white. During the 1906 alterations the drawing room was remodelled to become a bedroom and dressing room (Australian Council of National Trusts, Historic Homesteads of Australia, 1969 Vol 1 p 139).

The library to the house was fitted out in c1891, decorated in oak by Patrick Aylmer, the station carpenter to a design by Walter Butler (Historic Homesteads of Australia p 136 and The Australasian 30 June 1892 p 231). Aylmer was from Ireland and arrived at the station in 1876 (Australian Women’s Weekly 29 December 1965). Aylmer also worked on the carvings, panelling and ceiling to the new drawing room. Five hundred pieces of hand carved oak were used in the ceiling of the drawing room (Ibid.) Floors in the central part of the house are laid with ribbons of alternating jarrah and ash.

The collection of outbuildings around the house has often been described as a village. The evocation of a village atmosphere was far from accidental. Samuel Pratt Winter was reliant on a dependable workforce to run his station, which in 1862 comprised 12,380 of freehold and by 1870 about 14,000 acres (Forth op cit p 135). In the manner of the English and Irish estates that were so familiar to him, Samuel Pratt Winter sought to counter worker itinerancy by employing entire families on his estate. According to Kiddle, voluntary immigration created a “maddeningly independent” labour force that was forever moving from job to job. In the 1870s there were twenty-three men constantly on the wage roll at Murndal (Margaret Kiddle, Men of Yesterday, Carlton, 1961 p 285) but nine were drawn from three families. Murndal fielded its own cricket and football teams as well (Historic Homesteads of Australia p 132). This was not unusual for a large station in the nineteenth century.

The village atmosphere that was created at Murndal certainly impressed the journalist from The Australasian in 1910, who remarked on the air of general contentment on all sides, even down to the “smallest urchin at the lodge-gates.” It was reported of Samuel Winter Cooke that he could not countenance selling Murndal for “what would become of all these good folk on the station, who have throughout been dependent upon me, and who have served me so loyally all these years?” (The Australasian 19 March 1910, p 703). There was a mutual interdependence; the Winter Cookes relied on a dependable workforce; in return they upheld many of the traditions of the English and Irish estates, engendering loyalty by casting a paternalistic eye over families in their employ, and by providing a sense of community and belonging to the station. Before Samuel Winter Cooke donated land and money for the building of the Anglican church of St Peter’s at Tahara in 1881,occassional church services were held in the Murndal dining room (National Trust Newsletter, November 1972 p 5). Samuel Winter Cooke and the people who worked at Murndal attended St Peter’s Church “in the best English manner” (National Trust Newsletter, November 1972 p 5).

One of the most significant contributions by Samuel Winter Cooke to the English village atmosphere was the additions to the house in 1906. The work was carried out by architects Ussher & Kemp (Katrina Place, who is researching a PhD at University of Melbourne on Walter Butler, has located the drawings in the possession Russell Kemp, a great grand-nephew of Kemp). These improvements further emphasised the house as the centre of the estate. The half timber gables, leadlight windows and red tile roof re-rooted and enforced both the sense of authority and permanence by reference to the form and style of an Elizabethan manor house.

A gate lodge once guarded the main entrance from the road. The lodge is shown in a photograph illustrated in the facsimile edition of Victoria’s Representative Men at Home (first published 1904). It has been reproduced in several places, including Gordon Forth’s Winters on the Wannon (p 174). In 1910 the reporter for The Australasian noted the “urchins” at the lodge-gates (The Australasian 19 March 1910). The lodge still exists. It was removed to Wannon at an unknown date and is now owned by Ian Bell (information from Samuel Winter Cooke).

Associated People: Winter-Cooke FamilyMURNDAL - Permit Exemptions

General Exemptions:General exemptions apply to all places and objects included in the Victorian Heritage Register (VHR). General exemptions have been designed to allow everyday activities, maintenance and changes to your property, which don’t harm its cultural heritage significance, to proceed without the need to obtain approvals under the Heritage Act 2017.Places of worship: In some circumstances, you can alter a place of worship to accommodate religious practices without a permit, but you must notify the Executive Director of Heritage Victoria before you start the works or activities at least 20 business days before the works or activities are to commence.Subdivision/consolidation: Permit exemptions exist for some subdivisions and consolidations. If the subdivision or consolidation is in accordance with a planning permit granted under Part 4 of the Planning and Environment Act 1987 and the application for the planning permit was referred to the Executive Director of Heritage Victoria as a determining referral authority, a permit is not required.Specific exemptions may also apply to your registered place or object. If applicable, these are listed below. Specific exemptions are tailored to the conservation and management needs of an individual registered place or object and set out works and activities that are exempt from the requirements of a permit. Specific exemptions prevail if they conflict with general exemptions. Find out more about heritage permit exemptions here.Specific Exemptions:General Conditions:

1. All exempted alterations are to be planned and carried out in a manner which prevents damage to the fabric of the registered place or object.

2. Should it become apparent during further inspection or the carrying out of alterations that original or previously hidden or inaccessible details of the place or object are revealed which relate to the significance of the place or object, then the exemption covering such alteration shall cease and the Executive Director shall be notified as soon as possible.

3. If there is a conservation policy and plan approved by the Executive Director, all works shall be in accordance with it.

4. Nothing in this declaration prevents the Executive Director from amending or rescinding all or any of the permit exemptions.

Nothing in this declaration exempts owners or their agents from the responsibility to seek relevant planning or building permits from the responsible authority where applicable.

The registered land and landscape features and trees

* Erection or construction of roads and tracks and of fencing, gates, stockyards or any other forms of access and enclosure necessary for the continuation of pastoral or agricultural activities on the property provided that the works do not adversely affect the registered buildings.

* General horticultural maintenance.

* Repair and maintenance of irrigation systems associated with the garden dams.

* Repair, replacement or installation of other water systems necessary for irrigation which do not adversely impact on the existing dam schemes.

* Repair, replacement or installation of seating and other outdoor furniture.

Exterior of homestead

* Minor repairs and maintenance which replace like with like.

* Removal of extraneous items such as air conditioners, pipe work, ducting, wiring, signage, antennae, aerials etc, and making good.

Interior of homestead

* Painting or wallpapering of previously painted walls and ceilings provided that preparation or painting does not remove evidence of earlier paint or other decorative scheme. Evidence of earlier schemes should be reported to Heritage Victoria.

* Removal of paint from originally unpainted or oiled joinery, doors, architraves, skirtings and decorative strapping.

* Replacement of carpets and floor coverings.

* Removal or replacement of curtain track, rods, blinds and other window dressings.

* Installation, removal or replacement of hooks, nails and other devices for the hanging of mirrors, paintings and other wall mounted artworks.

* Refurbishment of existing bathrooms, toilets and en suites including removal, installation or replacement of sanitary fixtures and associated piping, mirrors, wall and floor coverings.

* Removal and replacement of existing kitchen benches and fixtures including sinks, stoves, ovens, refrigerators, dishwashers etc and associated plumbing and wiring.

* Installation, removal or replacement of electrical wiring provided that all new wiring is fully concealed and any original light switches, pull cords, push buttons or power outlets are retained in-situ. Note: if wiring original to the place was carried in timber conduits then the conduits should remain in-situ.

* Installation, removal or replacement of smoke detectors.

Registered outbuildings

* Repainting of corrugated iron roofs in existing hues.

* Minor repairs and maintenance which replace like with like. E.g corrugated iron should be replaced with corrugated iron, not Colorbond.

* Removal of extraneous items such as air conditioners, pipe work, ducting, wiring, signage, antennae, aerials etc, and making good.MURNDAL - Permit Exemption Policy

The purpose of the permit exemptions is to allow works that do not impact on the significance of the place to take place without the need for a permit. Repairs and maintenance which replace like materials with like are permit exempt.

The primary significance of Murndal is the buildings and landscapes within the approximate boundaries of the pre-emptive right. Landscaping, the garden dams scheme and the exotic tree planting scheme in the approximate area of the pre-emptive right are of primary significance.

The itemised trees are of primary significance. Other trees and plantings contribute to the significance of the place but are not individually significant in their own right. Permits and future planting should take account of the need to preserve the feel of the 18th century beautification approach to landscape rather than the need for outright preservation of individual trees.

The house and land has been in the continuous hands of one family, and each generation has added its own elements whilst respecting the work of previous generations. This is a good principle for future additions or alterations to the main house.

Alterations to the decorative scheme of the library, which appears to be an intact 1890s scheme, should not be made without a permit.

-

-

-

-

-

MURNDAL

Victorian Heritage Register H0289

Victorian Heritage Register H0289

-

DIGHTS MILL SITE

Victorian Heritage Register H1522

Victorian Heritage Register H1522 -

DUNROE

Southern Grampians Shire

Southern Grampians Shire -

EMU BOTTOM

Victorian Heritage Register H0274

Victorian Heritage Register H0274

-

-