KIRWANS BRIDGE

KIRWANS BRIDGE-LONGWOOD ROAD AND OVER GOULBURN RIVER, KIRWANS BRIDGE ROAD AND MACLEOD STREET KIRWANS BRIDGE, STRATHBOGIE SHIRE

-

Add to tour

You must log in to do that.

-

Share

-

Shortlist place

You must log in to do that.

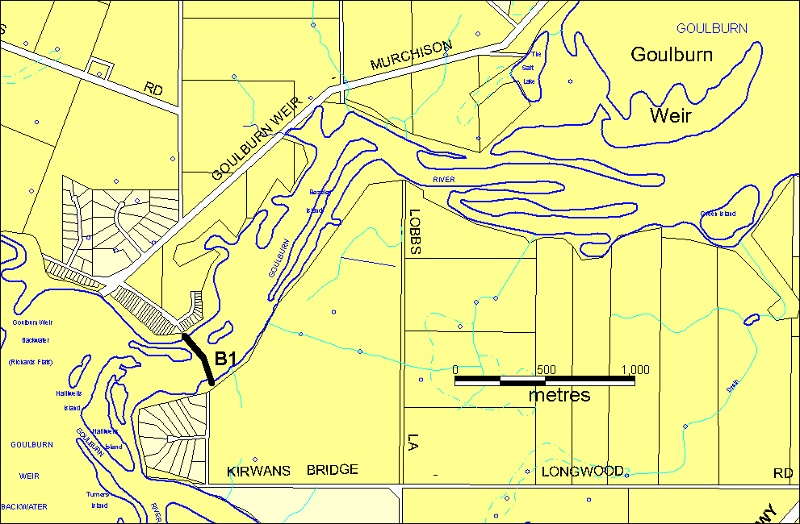

- Download report

Statement of Significance

The 310 metres long Kirwans Bridge is situated over the Goulburn River at Bailieston near Nagambie. It was opened in 1890, and is still in use for (one-way) motor traffic. The only comparable timber bridge in Victoria in terms of length is the 1927 Barwon Heads Bridge which is 308 metres long. In 1955 the bridge was modified by the construction of a new superstructure, in which its timber beams were replaced by RSJs, and its deck narrowed to single lane, with passing bays maintaining the full 21 feet (6.3 metres) original width. The bridge retains its original forty-eight spans of sixteen and a half feet (5 metres), and its original seven main river-channel spans of thirty-three feet (10 metres). Its tall timber trestles are largely immersed under Lake Nagambie. Remnants of its original squared beams and strutted corbels - one of only two remaining examples in Victoria - are clearly visible beside the bridge.

The bridge features a dramatic mid-stream bend, and is also unique in its incorporation of two vehicle passing-bays. It is set at the northern arm of Lake Nagambie, a very popular boating and fishing venue close to Melbourne. The distinctive and imposing nature of the bridge has seen it feature in State-wide commercial and social promotions.

Kirwans Bridge is of historical, scientific (technical) and aesthetic significance to Victoria.

It is of historical significance as a work directly associated with Alfred Deakin's dream of a great 'National' irrigation system based upon the construction of the Goulburn Weir. Consequently, with nearby Chinamans Bridge, it was built entirely with Victorian government funds, a factor in its large size. When opened in 1890, it provided access to Nagambie and the railway for the mining areas of Bailieston and Whroo. So significant was the access to Nagambie it provided for those living on the west of the Goulburn River that a threat to the bridge's continuing future in the mid-1950s led to a municipal secession movement that enlarged the Shire of Goulburn at the expense of Kirwans' original builders, the Shire of Waranga. The current narrowed timber deck with passing bays, supported by rolled steel joists placed over the ancient piers, remains a memorial to that municipal protest. It is one of Victoria's very oldest timber road bridges still in operation; very few are earlier. Kirwans Bridge is also one of a unique group of four large timber road bridges from the 1890s, of contrasting types, located on the Goulburn River between Seymour and Murchison; this is the last remaining group of large old timber river bridges in Victoria.

It is of scientific (technical) significance as one of only two extant Victorian timber bridges retaining vestiges of a colonial 'strutted-corbel' type of river-bridge design. Only at Kirwans Bridge and the Jeparit Bridge is it now possible to study examples of this historic European form of timber-bridge craftmanship. Although its visual effect is not greatly different from that of the equally rare and historic 'strut-and-straining-piece' design of nearby Chinamans Bridge, the detail and mechanics of the stringer-support system are structurally different. Kirwans Bridge also provides a remarkably successful example of engineering adaptation to changing vehicle needs over more than a century. It has an exceptionally long timber deck; no road bridge in Victoria is longer.

It is of aesthetic significance as a predominantly-timber structure whose exceptional length is accented by full timber side-rails, and which features a pronounced mid-stream bend and unique vehicle passing-bays. This aesthetic quality, unique in Victoria, is accentuated by the bridge's setting just above the broad waters of Lake Nagambie.

-

-

KIRWANS BRIDGE - History

INFORMATION SUPPLIED IN SUPPORT OF NOMINATION BY NATIONAL TRUST

During the 1880s Alfred Deakin enthused Victorians with a dream of the potential agricultural bonanza that could be created by using irrigation to transform the fertile but arid Murray-Goulburn plains into dairies and orchards. Central to Deakin's vision were weirs across the impetuous Goulburn River, to dam its melting snows and transform this ancient waterway which periodically and destructively inundated large areas of low-lying farmland, into an economically fruitful irrigation channel. Deakin's irrigation visions involved a big weir below Nagambie, which could be used to create vaste artificial lakes beloved of campers and fishermen today. (On Deakin and irrigation, see Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol. 8, 'Alfred Deakin'; for Deakin's comments on the Goulburn River situation, see P. B. F. Alsop, 'Bridges Over The Goulburn River at Nagambie, Victoria', (unpublished paper) Geelong, Victoria, February 1991.)

Kirwans Bridge, and nearby Kerris (Chinamans) Bridge built by the Goulburn Shire at the same time, were unusual in being built by rural municipalities entirely from State funding, as compensation for flooding of local traffic facilities by the new Goulburn Weir. These big bridges had to be built quickly, because of the near-completion of the impressive weir that would submerge previous roads and bridges connecting the south-east of the Waranga Shire hinterland with Nagambie.

By mid-1889 a sense of strident urgency coloured correspondence between Victoria?s State Water Supply Department and the adjacent shires of Goulburn and Waranga, which had long been at war over problems in bridging their shared municipal boundary: the formidable Goulburn River. The shires were warned that with the weir expected to be completed by year?s end, many ratepayers would be isolated when their earlier 'lifeline' (Kettles Bridge near Nagambie) was inundated. Such a 'National Work' could not wait on municipal bickering, and the Water Supply Department threatened to take the bridging of the swollen Goulburn River into its own hands. (Rushworth Chronicle, 24 May 1889)

Faced with the unpleasant prospect of losing control of large sums of State compensation for road and bridge building in areas soon to be flooded, the shires stopped their traditional warring over bridges and agreed on a need for two large bridges to replace Kettle's Bridge. They also agreed that they needed very large sums of State money. Wrangling between the shires temporarily ceased, while arguments between municipalities and State Water authorities over estimated costs increased, and the weir wall crept ever-closer to completion.

That the need for two large and expensive bridges was quietly conceded by State authorities, indicates that they were keen to reach an agreement which absolved them from any future bridging liabilities. Waranga Shire based on Rushworth was intent on getting as much State funding into the municipal coffers as possible. Their big bridge over the Goulburn to replace Kettles was seen as benefiting long-term Nagambie rivals, but it was also a convenient tool to lever money from State authorities: money which they hoped to use more widely. Waranga Shire insisted that in bridge construction 'too many cooks spoil the broth', so it was agreed that Waranga take responsibility for constructing Kirwans while Goulburn handled the construction of Kerris (Chinamans) Bridge a few miles upstream. (Goulburn Advertiser, 6 Sept. 1889) By mid-1889 the race was on for first picking at the shared pool of State funding.

A joint municipal delegation had fraternized with uncharacteristic amiability as its members bumped over submerged logs and sandbars along the Goulburn River on the Nagambie-based paddle steamer, Agnes, inspecting possible bridge sites and sharing riverside victuals and local wine. There were three possible sites for the more northerly of the two new bridges, and the State Water Supply Department's engineer favoured the middle site which was one and a half miles north of Kirwans. However, a majority of local residents appeared keen to spend their government booty at Kirwans, probably unaware of just how wide the flooded weir would be at that point, and of the extent of road cuttings needed to link this bridge with the earlier road from 'Kettles' to Nagambie. (Rushworth Chronicle, 24 May 1889) With Rushworth's municipal authorities intent on building a case for extorting as much government funding as possible, such 'difficulties' passed unnoticed. Meanwhile, State authorities used the columns of Melbourne's Argus newspaper to publicize their view that '... the local bodies wish for a greater expenditure than the official engineer deems necessary.' (Goulburn Advertiser, 5 July 1889, citing Argus 1 July 1889)

The municipalities eventually agreed to depart from their costing of 40,000 pounds, as against the State's costing of 10,000 pounds, and by late 1889 all had agreed on a joint compensation sum of 17,000 pounds (Goulburn Advertiser, 6 Sept. 1889). Ten thousand pounds was allocated for the two bridges and their road approaches (Goulburn Advertiser, 25 Oct. 1889) (although Rushworth-based councillors soon decided that costly road-cuttings over the river were not 'bridge approaches', to Nagambie's dismay). Privately, Waranga's councillors rubbed their hands in glee in the belief that any 'surplus' from the State booty was theirs: as yet unaware that bridge contractors faced with frightening risks from an ever-rising weir wall and unpredictable winter and spring rainfall, along with a nasty and close 'deadline' when the weir eventually filled, would tender high.

Although compelled to publish all tenders for projects funded by ratepayers, Waranga councillors were extremely secretive about State-funded projects. Not even the Shire Minutes could be trusted with tendering details for Kirwans Bridge. However, in September 1889, councillors noted that their original bridge claim had been drastically cut by State authorities, while the State Water authorities simultaneously approved the Shire's original expensive bridge plans (Goulburn Advertiser, 6 Sept. 1889). Plans for the new bridge would be available to potential contractors at Rushworth's Shire Hall from 1st October 1889, and a preliminary notice that tenders would be called in two months was to be published in the local press and Melbourne's Argus and Age. A joint meeting of neighbouring shire representatives late in October had lost any signs of the amiability expressed while sailing the Goulburn on Nagambie's paddle steamer, and drinking Nagambie wine.

Waranga's delegates were jealous of Goulburn's big sum for bridge building, since they considered Kerris (Chinamans) an 'optional extra' funnelling even more Waranga ratepayers into Nagambie. As problems piled up, the tendering process was delayed, and in November Waranga councillors threatened to hand the problem back to State water authorities (Goulburn Advertiser, 25 Oct., 8 Nov., 1889). Meanwhile, the Nagambie Steam Navigation and Sawmill Company, proprietors of the good ship Agnes, sent a solicitor's letter to the Waranga Shire indicating that their bridge plans allowed inadequate waterway for river steamers, and that unless greater waterway were provided they would intervene at law to prevent bridge construction (Goulburn Advertiser, 6 Dec. 1889). Rushworth had no objection to expensive 'drawbridges' for river boats, provided that Nagambie paid.

Meanwhile, councillors at Nagambie pondered Rushworth's plans for Kirwans, and decided (since there were expensive road-cuttings on their side of the river) that the actual bridge structure was unnecessarily expensive. Goulburn's Shire Engineer was accordingly instructed to modify Waranga Shire's plan, and send it back to them (Goulburn Advertiser, 6 Dec. 1889). Waranga councillors never complained about cheaper plans, and early in January the State Water authorities acknowledged receipt of altered specifications and drawings for Kirwans, noting that 'the alteration on land spans from 33 feet to 16 feet 6 inches should materially reduce the cost of the bridges'. Thus did Kirwans depart from its original vision as a large timber bridge of totally 'strutted-corbel' construction, to one where strutted-corbel construction would be reserved for the main river channel of the new weir situation. The fact that Kerris (Chinamans) plans escaped retaliation from Rushworth's councillors can largely be explained by the fact that Goulburn councillors did not show Waranga councillors their plans until after tenders were accepted! Thus Chinamans remains today a fully-strutted structure (Public Record Office, Laverton, VPRS 3908, UNIT 4, P. 506).

'Cheaper' plans notwithstanding, Waranga councillors were shocked by the costings of tenderers for the Kirwans job. Tenderers' fears of risks and complications from ever-rising waters as the weir wall progressed were not unfounded, and the first contractor for Kerris (Chinamans) gave up and forfeited his plant when his piles disappeared under winter waters in 1890. The original tenders for Kirwans being considered outrageous, new tenders were called returnable at Rushworth on 20th January, and a special (and highly-secretive) meeting of selected Waranga councillors considered tenders that day. Although no tender details were confided to the Minutes, the record suggests that only one (compromise?) tender was received at this meeting, and its acceptance was delayed while councillors sought to get reassurance from State water authorities that extra costs would be picked up in Melbourne. State authorities were now desperate to get bridges up before the weir was completed, and a telegram from the water authority's Chief Engineer early in February reassured councillors that he had advised the Minister to provide the extra funding needed for Kirwans (P.R.O. Laverton, VPRS 3908, unit 4, p. 519; Goulburn Advertiser, 24 Jan., 7 Feb. 1890).

Thus reassured, Waranga councillors gave contractors Dainton and Hesford the job, and the race for government funds was on in earnest as Kerris (Chinamans) also proceeded under Nagambie supervision. Contractor Dainton asked to be allowed to use (local) hewn timber instead of sawn timber for stringers, corbels and gravel beams, 'to expedite the work'. Councillors considered hewn timber as good as (if not better) than sawn, and this meant work for shire residents rather than importing sawn timber into the shire (Goulburn Advertiser, 7 Feb. 1890). No indications are given as to timber used, but decaying stringers visible beside Kirwans today look like red gum. With cost-cutting and speed of construction the orders of the day, this should not surprise, red gum being ready to hand near the river and iron bark from Whroo forest (for such a large structure) being considerably more expensive in terms of government royalties and wages for working.

Although some locals questioned the quality of bridge piles being used at Kirwans, talking of 'plugged' piles and knot holes, this bridge contract went ahead by leaps and bounds while the contractor up-river at Kerris tore his hair because of his inability either to get sufficient high-quality bridge-timber on credit, or to get adequate 'advances' from Goulburn Shire to buy timber. Goulburn councillors showed signs of panic as the 'vouchers' for payments to Waranga's contractor (totalling several thousands of pounds) steadily rolled in for signature, while their own bridge piles were under the Goulburn River's apparently ever-rising waters and work on Kerris (Chinamans) at a standstill.

Whereas Kerris bridge appears today to have an obvious function in connecting major centres like Nagambie and Heathcote and old mining centres like Costerfield and Graytown en route, the purpose of the big and expensive bridge at Kirwans in 1890 is now less obvious. In 1890 Kirwans was described as being at Bailieston, then a mining and postal township with two booming hotels. Although within Waranga Shire, the township was associated with Nagambie rather than Rushworth, travellers thence being advised to take a train to Nagambie and catch the coach for a final nine-mile stage over Kettle's (later, Kirwans) Bridge. Bailieston's little populace largely depended on antinomy and quartz mining. Further along the road and more associated with Rushworth was the gold-mining township of Whroo, with its post office, savings bank, three hotels, one church (for the sober of all denominations), mechanics' institute and free lending library. Whroo still claimed to indulge in alluvial as well as quartz mining for gold, and was proud of its rich Balaclava Hill claim. Travellers to Whroo were advised to entrain to Rushworth, and board the coach thence (Victorian Municipal Directory, 1891, pp. 510-11).

The coming of the railway to link Rushworth with Nagambie had already taken away much direct traffic that had earlier traversed rough bush tracks between Nagambie and Rushworth. Obviously, miners and farmers across the river to the north-west of Nagambie, depending on Nagambie for supplies and market links, considered the bridge to be vital. With the railway link no longer available, the road through Bailieston by Reedy Lake and the Whroo ironbark forest and mining relics to Rushworth, now provides an interesting tourist route for people not in a hurry. In 1890 that connection with the timber riches of Whroo forest remained important for Nagambie district, especially when bridges needed to be constructed.

Waranga councillors visited the Kirwans site in May 1890, and expressed surprise at the 'splendid progress'. Nearly all piles were driven, and in the main river-channel section the whole substructure was complete with tie-beams firmly bolted 'so that no ordinary flood can now interfere with the completion.' Doubtless, the contractors were relieved (Goulburn Advertiser, 23 May 1890). Among rare relevant surviving documents that I have located in Water Supply Department archives, is a telegram from Rushworth saying that money due for works at Bailieston has not arrived, terminating with a big 'Why?'. Nagambie-based councillors hinted at illicit 'influence'behind the scenes, with Rushworth apparently in line for big cash input from Melbourne while their own bridge works were hopelessly inundated. Kirwans would be completed by 8th of November, 1890.

Despite modifications to suit a trimmed budget, the completed Kirwans Bridge was an impressive sight. It was reported to be 1225 feet long, with 48 openings of sixteen feet six inches over what had previously been dry land, and seven 'strutted-corbel' spans of 33 feet covering the old river channel. These span dimensions do not 'add up' to the stated deck length and the correct figure was presumably 1025 feet, or approximately 308 metres, which equates with current reality. Thirty-six piles, each of sixty-feet length, were used in the main river channel section. The neatly squared stringers measured sixteen inches by fourteen inches by 36 feet length in the main channel section. Long squared corbels were of sixteen-inch by twenty-two inch timber, and the iron fastenings, bolts and spikes used in the structure weighed twenty tons. The bridge was twenty-one feet wide and its transverse decking of nine-inch by six-inch planking was designed for heavy wagons and steam traction engines (Nagambie Times, 7 Nov. 1890). By modern engineering standards, Kirwans Bridge was certainly not 'underbuilt' for its expected loadings. The completion was just in time, because by December 1890 weir waters were rising to normal irrigation levels and covering the ancient river flats at Kirwans.

Waranga Shire councillors at Rushworth were not happy when the Water Supply Department informed them in November 1890 that they would get eleven thousand pounds, and that the remaining six thousand pounds of the joint fund was being reserved for Goulburn Shire to complete its big road-cutting down to Kirwans Bridge, and to pay the second contractor at Kerris (Chinamans) Bridge in a more difficult and expensive bridge-construction project at that soon-to-be-flooded site. Cr Brisbane contended that the Water authority had 'gone back on its word', while Cr Healy continued to complain that Goulburn Shire was 'getting more than it ought'. Cr Mason was more philosophical, commenting that 'the increased cost of the bridges had put the calculations out a little' (Nagambie Times, 21 Nov. 1890). The long-anticipated 'surplus' of government funds had evaporated at Rushworth, while rivals across the river at Nagambie who had always known there would be no 'surplus' were now concerned to minimize their losses on their own disastrous bridge project.

When the biggest flood on the Goulburn since the legendary 'monster' of 1870 hit, in September 1916, distant Reedy Lake would be joined to the Goulburn River by a surging inland sea, and Waranga Shire's approaches to both bridges would be decimated. 'Chinamans' stood defiant, apart from minor damage to timber wing walls and badly scoured approaches, but Kirwans was a sorry sight with its proud strutted-corbel river spans sagging towards the water where the sixty-feet piles had been undermined by scouring. It was a nasty sight for residents of Bailieston and district, and for Waranga councillors.

Old residents hotly debated whether the new flood exceeded the 'whopper' of 1870 that had decimated bridges throughout the area. But Goulburn Weir had not been there in 1870, and the impeded flood waters on the morning of Tuesday 26 September 1916 were piled high above the weir wall, only the tops of its electric-light standards being visible. Only when the surging waters had dropped again was it possible to see the havoc wreaked upon Kirwans' timber structure, and all traffic was diverted over Kerris (Chinamans) Bridge which had quick repair works performed on its battered approaches (Nagambie Times, 29 Sept., 6 Oct. 1916). Because the extent of damage by erosion of pier foundations was invisible below the waters, initial estimates of repair costs (in the vicinity of three hundred pounds) were unrealistically low.

Local councillors had initially assumed that Kirwans (like Kerris nearby) was by then the responsibility of the recently-formed Country Roads Board, with its access to State funding. However, with railways linking Nagambie to Rushworth, the Board did not consider the old miners' route to Bailieston and beyond a 'Main Road' deserving of State funding. Councillor Gordon of Goulburn Shire had political influence, and he suggested in October 1916 'that this was a case in which they might well approach the Government for assistance'. It was moved that Councillor Gordon and Goulburn Shire's President wait upon the Minister for Public Works in this matter, and that Waranga Shire be asked to send representatives (Nagambie Times, 13 Oct. 1916).

Kirwans Bridge had a gravelled surface over its heavy timber decking, because in 1916 'fully half of the gravelled track' was swept off. The real damage, however, had occurred at the big bend in the 'v' shaped deck of Kirwans, sixty to seventy feet of the timber superstructure having collapsed due to scouring of the old river channel below. Waranga Shire seemed initially much less concerned about the bridge that they had built, than did Goulburn Shire neighbours. As late as 12th November, Councillor Gordon of the Goulburn Shire stated that the proposed visitation upon the Minister in search of State funds had been postponed, because Waranga Shire's Engineer had not yet inspected the damage and estimated repair costs. Waranga Shire's President had been contacted to impress upon him the urgency of repairs (Nagambie Times, 17 Nov. 1916). Waranga ratepayers having to make the long detour around by Kerris (Chinamans) to Nagambie were doubtless impatient with Rushworth's leisurely approach.

In 1916, however, Kirwans Bridge was still situated on the river boundary line between the two shires, and Waranga Shire could not avoid responsibility. Eventually, at a meeting of Waranga Shire on 14th November, 1916, a motion was passed that the President be appointed to join the Goulburn Shire's representatives in waiting upon the Minister for Public Works, to ask for a State bridge-repair grant. With heavy rains continuing to fall, the sagging structure at Bailieston was deteriorating, but only at this meeting was Waranga's Engineer formally instructed to confer with Goulburn's Engineer at Kirwans. By December councillors at Rushworth were beginning to take notice, fearing they would lose much of the bridge's structural timber that was now swinging perilously close to water. However, Waranga's Engineer had still not inspected the damage. With the bridge urgently needed to handle the coming harvest, it was suggested that cables be strung below the superstructure, to allow vehicle passage. But the damage was more serious than then realized (Murchison Advertiser, 17 Nov., 8 Dec. 1916.)

On 13th December, a joint deputation that included Waranga Shire's Engineer and John Gordon M.L.A. waited upon the Minister for Public Works, who appeared sympathetic and promised to send an engineer from his department to assess the damage, and on receipt of this official report to favourably consider the request for State aid. The engineer from Melbourne arrived on 3rd of January 1917. A Waranga Shire meeting on 2nd of January had decided that, should agreement be reached with the State authorities, tenders for the bridge's reconstruction could be called at its next meeting pending the Government's decision on the extent of financial assistance. State authorities obviously realized the urgency of repairs, to avert more expensive works later, and by early February had offered one hundred and eighty seven pounds conditional upon the shires contributing like amounts (Nagambie Times, 15 Dec. 1916; Murchison Advertiser, 5 Jan., 9 Feb. 1917).

The extent of replacement timbers required is indicated by the size of the initial tenders for 'supply and delivery of piles and sawn or hewn timber for Kirwans bridge, near Nagambie', that of local timber-cutter J. T. Hipgrave for two hundred and twenty seven pounds and fifteen shillings being the lowest received. Hipgrave's separate quotation for 'timber work and repairs to Kirwans bridge' was also easily the lowest received, at two hundred and fifty three pounds and ten shillings, and he was given the job (Murchison Advertiser, 9 Feb. 1917). By April the real nature of the disaster at Kirwans became more obvious, as pile-driving got under way. Despite increasing the length of piles over those first ordered, thus increasing costs, 'there appears to be no hard bottom at all, even at 25 feet driven depth.' With the alluvial banks of the old river channel saturated in irrigation water for decades, any 'bottom' that the 'dry-land' contractor of 1890 might have claimed to find had apparently disappeared.

The vibrations of a four-ton donkey engine seated upon the 'firm' structure for pile-driving purposes, caused two apparently sound timber piers to 'settle' alarmingly. To allay this damage would cost a further one hundred and fifty pounds, but councillors were warned that unless they did it while machinery was on site, it would cost much more. They must have rued the day that they accepted State funds for this bridge's construction, to allow their farmers and miners easy access to Nagambie. Their engineer advised finding even longer piles to strengthen the main-channel piers. Goulburn Shire's representatives meeting at Nagambie remained keen to maintain access from the Waranga hinterland to their town centre, and readily agreed to additional contributions (Murchison Advertiser, 6 Apr. 1917, Nagambie Times, 20 Apr. 1917).

It seems likely that at least the longest piles used in reconstruction were red gum, since they were imported from Murray River forests near Cobram. Shorter and medium-length piles were obtained locally, and we have no indication of the timber used (apart from the fact that Waranga Shire's engineer favoured local iron bark over red gum, generally). The need to await timber 'imports' held up repairs, but by 3rd of July 1917 (more than nine months after the damage occurred) Waranga Shire's engineer could report that repairs were completed and that Kirwans Bridge was again open to traffic. The coach to Bailieston could henceforth avoid its long enforced detour around via Kerris (Chinamans) Bridge (Murchison Advertiser, 8 June, 6 July 1917).

Despite fears that Kirwans was a sitting-duck for the next big wash along the Goulburn, the reconstructed bridge gave long and satisfactory service through the troubled eras of Great Depression and World War 2, and was still coping with its traffic loads in the early 1950s when rural Australia's economy was revolutionized by American stock-piling of Australian wool for Korean War purposes. Virtually overnight, large American sedan cars appeared in farming areas to replace the battered old Chevrolet, Dodge or Ford touring cars of the 1920s. Farmers could now afford large new trucks and tractors and farm machinery, and ageing pre-war roads and bridges that had lacked proper maintenance through the long war years felt the impact. Any surviving original timber stringers in Kirwans Bridge would have been sixty-three years old in 1953: a great age for timber bridge components in a moist weir environment. The big hewn red gum stringers in the similarly-aged bridge across the Goulburn River at Seymour had been replaced by rolled steel joists in 1933.

At a meeting of Waranga councillors at Rushworth in January 1953, 'Cr. Keily asked what was the position in regard to Kirwans bridge and the proposed deputation to the Minister of Public Works.' Councillors decided to arrange a deputation to the Minister (P.R.O., Laverton, VPRS 3908, unit 20, 8 Jan. 1953, p. 265). Waranga councillors sitting at Rushworth had always felt that Kirwans Bridge benefited Nagambie rivals, and the intervening years had not been kind to mining interests of settlements like Bailieston and Whroo. By 1953 Whroo was just another Victorian 'ghost town', and Bailieston was more interested in sheep and wool than antinomy and gold.

If Waranga councillors meeting at Rushworth had not shown any sense of urgency when flood waters devastated Kirwans Bridge in 1916, they appeared positively bored when local ratepayers indicated that Kirwans needed serious repairs in 1953. Nagambie had long been maintaining the trafficability of Kirwans. A Waranga Shire meeting in February 1953 moved that, before approaching the Minister of Public Works, council representatives should confer with Goulburn councillors. Goulburn representatives were asked to attend the next monthly Waranga Shire meeting at Rushworth, but it seems that they may have been taking initiatives of their own. They thanked Waranga Shire for the invitation to parley, 'but in view of the inspection by members of the Country Roads Board of Kirwans Bridge on 11th of February 1953, consider visit should be postponed' (P.R.O. Laverton, VPRS 3908, unit 20, 3 Feb. 1953, p. 272; 3 March 1953, p. 279).

Representatives of both interested shires were present when C.R.B. officers inspected Kirwans Bridge, and the C.R.B. requested the two shire engineers to make a thorough inspection and submit reports on estimated repair costs. C.R.B. officials were sufficiently concerned to suggest an immediate load limit, so signs limiting loads to thirty hundredweight were set up. On giving the bridge a closer inspection, the two local engineers seem to have been positively alarmed, so Goulburn Shire decided to close the bridge. Waranga Shire was consulted, and after hearing its engineer's comments decided that 'both ends [were] to be substantially fenced' to keep traffic off. It appeared to residents of Bailieston and district that Rushworth was simply wiping its hands of local bridging problems. Tradition has it that locals helped themselves to timber from the ageing structure, convinced that its death warrant had been signed. By mid-July, 1953, the bridge had been fenced off and warning notices erected (P.R.O. Laverton, VPRS 3908, unit 20, 3 March p. 279, 4 Aug. 1953, p. 323).

In October a letter from a Nagambie resident to Waranga Shire pointed to the sad state of the roads in the Goulburn Weir area under Rushworth control: 'He thought it would be to the advantage of the Council if some announcement was made regarding proposed repairs to Kirwans Bridge as press reports so far indicated that the Goulburn Shire was doing all the work in this regard' (P.R.O. Laverton, VPRS 3908, unit 20, 6 Oct. 1953, p. 340). Sporadic grading by Rushworth authorities did little to quieten growing local feeling against the Shire of Waranga.

By January 1954, Waranga Shire was receiving correspondence from a body calling itself the Waranga and McIvor Severance Committee. McIvor Shire authorities shared with Goulburn Shire the responsibility to maintain the other ageing Goulburn River bridge upstream at Mitchellstown, and they were affected by a growing desire throughout the Goulburn Weir area to strengthen links with Nagambie. The Severance Committee wanted Waranga councillors to pursue the earlier idea of meeting with Public Works authorities to discuss the bridge problem, and Rushworth was agreeable provided that C.R.B. authorities were advised of the date of the suggested conference (P.R.O. Laverton, VPRS 3908, unit 20, 7 Jan. 1954, p.364).

In February 1954 Waranga Council received legal correspondence from the new Severance Committee, asking whether it was in favour of annexation of its south-east section to Goulburn Shire. Rushworth councillors denied knowledge of any severance movement. By that time their ratepayers in the vicinity of the Goulburn Weir had lost all patience with Waranga's apparent indifference to the bridge's future. In a last desperate effort, Waranga Shire had approached the Country Roads Board about getting the old road linking Nagambie with Rushworth via Bailieston and Whroo declared a 'Forest Road'. Such a classification would have made both road and bridge a State financial responsibility, but the Country Roads Board regretted it was not in a position to declare more Forest Roads (P.R.O. Laverton, VPRS 3908, unit 20, 7 Jan. 1954,2 Feb. 1954, pp. 372-3).

By March 1954 it was apparent that the bridge issue was going to blow Waranga Shire apart. A delegation of Bailieston ratepayers, with their Nagambie solicitor, attended at Rushworth to argue their severance case. The Severance Committee had already petitioned the Governor in Council for annexation to Goulburn Shire, and Waranga councillors said that the normal local-government process could take its course. Related correspondence from the Minister of Public Works was referred to the Shire's solicitor. A poll of ratepayers in the disaffected area was duly held, and in October 1954 the Public Works Department advised Waranga Shire of the unwelcome result (P.R.O. Laverton, VPRS 3908, unit 20, 7 Jan. 1954,3 March 1954, p. 383, 4 May 1954, p. 400, 7 Oct. 1954, p. 440).

The Kirwans Bridge issue had significantly changed local government boundaries, and Goulburn councillors were committed to renovating the old timber structure that would henceforth connect numerous ratepayers to their municipal centre at Nagambie. In August 1955 Goulburn Council told Waranga councillors that 'they considered both shires should bear their share of cost of any repairs up to date of severance'. This correspondence suggests that Goulburn Shire was then repairing Kirwans Bridge. The letter stated that 'it had always been the policy of the shire to inform Waranga when it intended to carry out any work on this bridge'. The nameless bridge could have been no other than Kirwans (P.R.O. Laverton, VPRS 3908, unit 20, 7 Jan. 1954,2 Aug. 1955, p. 527).

During the second half of 1955, Kirwans Bridge apparently underwent major reconstruction. Its broad timber deck was drastically narrowed, with occasional 'passing bays' utilizing the full original width of substructure. More significantly, the huge squared stringers and corbels of an earlier era of bridge construction were replaced in the renovated section of the bridge by rolled steel joists. Kirwans Bridge is still largely of timber construction, the only non-timber element being its steel joists hidden below deck. Though narrowed down, it retains its impressive length of timber deck and side-rails, and the curious angled construction that impresses all who see it. It retains vestiges of the original 'strutted corbel' design, and examples of the huge squared beams that long carried traffic over Lake Nagambie.

Its very long and very distinctive deck structure, in conjunction with an unusual setting over the broad waters of Lake Nagambie, combine to provide a rare and increasingly valued aesthetic experience. For example, it has featured in marketing of new motor vehicles in the journal Royal Auto. In March 2000 it was the setting for one of the Melbourne Food and Wine Festival's 'long lunches', a single dining table set the length of its deck. It is situated in a summer paradise for holiday-makers and fishermen.KIRWANS BRIDGE - Assessment Against Criteria

Criterion A

The historical importance, association with or relationship to Victoria's history of the place or object.

It is of historical significance as a work directly associated with Alfred Deakin's dream of a great 'National' irrigation system based upon the construction of the Goulburn Weir.

Consequently, with nearby Chinamans bridge, it was built entirely with State funds, a factor in its size.

When opened in 1890, it provided access to Nagambie and the railway for the mining areas of Bailieston and Whroo.

So significant was the access to Nagambie it provided for those living on the west of the Goulburn River, that a threat to the bridge's continuing future in the mid-1950s led to a municipal secession movement that enlarged the Shire of Goulburn at the expense of Kirwans' original builders, the Shire of Waranga. The current narrowed timber deck with passing bays, supported by rolled steel joists placed over the ancient piers, remains a memorial to that municipal protest. No other bridge whose threatened closure has caused a re-drawing of the municipal map of Victoria, as happened around the Goulburn Weir in the mid-1950s, is known.

Criterion B

The importance of a place or object in demonstrating rarity or uniqueness.

It is of scientific (technical) significance as one of only two extant Victorian timber bridges retaining vestiges of a colonial 'strutted-corbel' type of river-bridge design. Although its strutted visual effect is not greatly different from that of the equally rare and historic 'strut-and-straining-piece' design of nearby Chinamans Bridge, the detail and mechanics of the stringer-support system are structurally different. Because of the removal of half of the deck, the remnants of its original squared beams and strutted corbels are clearly visible beside the bridge.

Kirwans Bridge has an exceptionally long timber deck; no road bridge in Victoria is longer.

It is one of Victoria's very oldest timber road bridges still in operation.

Criterion C

The place or object's potential to educate, illustrate or provide further scientific investigation in relation to Victoria's cultural heritage.

Kirwans Bridge has the potential to educate and illustrate the history of timber bridge building in Victoria. Only at Kirwans Bridge and the Jeparit Bridge is it now possible to study examples of this historic European form of timber-bridge craftmanship.

Criterion D

The importance of a place or object in exhibiting the principal characteristics or the representative nature of a place or object as part of a class or type of places or objects.

It is one of a unique group of four large timber road bridges from the 1890s, of contrasting types, located on the Goulburn River between Seymour and Murchison; this is the last remaining group of large old timber river bridges in Victoria.

Criterion E

The importance of the place or object in exhibiting good design or aesthetic characteristics and/or in exhibiting a richness, diversity or unusual integration of features.

Kirwans Bridge is of aesthetic significance as a predominantly-timber structure of exceptional length.

Kirwans Bridge features a dramatic mid-stream bend, and is also unique in its incorporation of two vehicle passing-bays. This is accented by full timber side-rails.

Kirwans Bridge's rare aesthetic quality is accentuated by the its setting just above the broad waters of Lake Nagambie. Lake Nagambie a very popular boating and fishing venue close to Melbourne.

Kirwans Bridge provides a remarkably successful example of engineering adaptation to changing vehicle needs over more than a century.

Criterion F

The importance of the place or object in demonstrating or being associated with scientific or technical innovations or achievements.

Criterion G

The importance of the place or object in demonstrating social or cultural associations.

The distinctive and imposing nature of Kirwans Bridge has seen it feature in State-wide motor-car advertising and social promotions.

Criterion H

Any other matter which the Council considers relevant to the determination of cultural heritage significanceKIRWANS BRIDGE - Permit Exemptions

General Exemptions:General exemptions apply to all places and objects included in the Victorian Heritage Register (VHR). General exemptions have been designed to allow everyday activities, maintenance and changes to your property, which don’t harm its cultural heritage significance, to proceed without the need to obtain approvals under the Heritage Act 2017.Places of worship: In some circumstances, you can alter a place of worship to accommodate religious practices without a permit, but you must notify the Executive Director of Heritage Victoria before you start the works or activities at least 20 business days before the works or activities are to commence.Subdivision/consolidation: Permit exemptions exist for some subdivisions and consolidations. If the subdivision or consolidation is in accordance with a planning permit granted under Part 4 of the Planning and Environment Act 1987 and the application for the planning permit was referred to the Executive Director of Heritage Victoria as a determining referral authority, a permit is not required.Specific exemptions may also apply to your registered place or object. If applicable, these are listed below. Specific exemptions are tailored to the conservation and management needs of an individual registered place or object and set out works and activities that are exempt from the requirements of a permit. Specific exemptions prevail if they conflict with general exemptions. Find out more about heritage permit exemptions here.Specific Exemptions:General Conditions:

1. All alterations are to be planned and carried out in a manner which prevents damage to the fabric of the registered place or object.

2. Should it become apparent during further inspection or the carrying out of alterations that original or previously hidden or inaccessible details of the place or object are revealed which relate to the significance of the place or object, then the exemption covering such alteration shall cease and the Executive Director shall be notified as soon as possible.

3. If there is a conservation policy and plan approved by the Executive Director, all works shall be in accordance with it.

4. Nothing in this declaration prevents the Executive Director from amending or rescinding all or any of the permit exemptions.

5. Nothing in this declaration exempts owners or their agents from the responsibility to seek relevant planning or building permits from the responsible authority where applicable.

Exemptions:

* Minor repairs and maintenance which replace like with like.

* reconstruction of the bridge to plans and specifications approved by the Executive Director

* Emergency and safety related works.KIRWANS BRIDGE - Permit Exemption Policy

The significance of this bridge lies mainly in its design elements and construction materials. Permits should be granted for works which preserve its unique character.

-

-

-

-

-

KIRWANS BRIDGE

Victorian Heritage Register H1886

Victorian Heritage Register H1886

-

"1890"

Yarra City

Yarra City -

'BRAESIDE'

Boroondara City

Boroondara City -

'ELAINE'

Boroondara City

Boroondara City

-

-