Back to search results

WOMBEETCH PUYUUN GRAVE MONUMENT & DAWSON FAMILY GRAVE

CEMETERY ROAD CAMPERDOWN, CORANGAMITE SHIRE

WOMBEETCH PUYUUN GRAVE MONUMENT & DAWSON FAMILY GRAVE

CEMETERY ROAD CAMPERDOWN, CORANGAMITE SHIRE

All information on this page is maintained by Heritage Victoria.

Click below for their website and contact details.

Victorian Heritage Register

-

Add to tour

You must log in to do that.

-

Share

-

Shortlist place

You must log in to do that.

- Download report

IMG 9899

On this page:

Statement of Significance

Wombeetch Puyuun Grave Monument & Dawson Family Grave is located on Eastern Maar Country

What is significant?

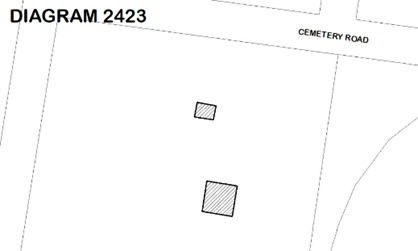

The Wombeetch Puyuun Grave Monument (1885) commissioned by James Dawson, including its immediate setting and tree to the west, and the Dawson Family Grave (c.1879-1929) both located in the Camperdown Cemetery.

How is it significant?

The Wombeetch Puyuun Grave Monument and Dawson Family Grave is of historical significance to the State of Victoria. It satisfies the following criteria for inclusion in the Victorian Heritage Register:

Criterion A

Importance to the course, or pattern, of Victoria's cultural history.

Criterion B

Possession of uncommon, rare or endangered aspects of Victoria’s cultural history.

Criterion G

Strong or special association with a particular present-day community or cultural group for social, cultural or spiritual reasons.

Criterion H

Special association with the life or works of a person, or group of persons, of importance in Victoria’s history.

Why is it significant?

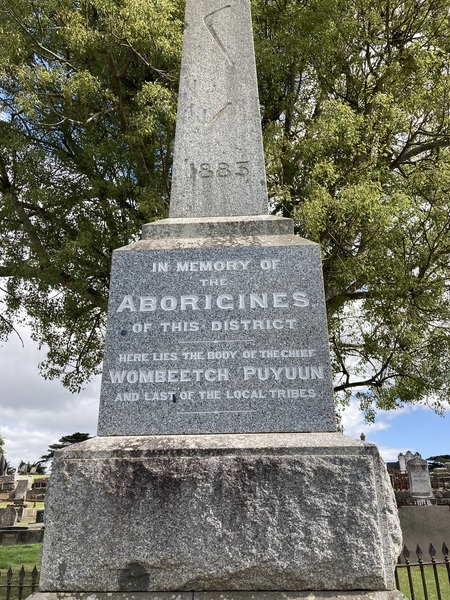

The Wombeetch Puyuun Grave Monument and Dawson Family Grave is historically significant for its capacity to demonstrate the rapid and devastating effect of European colonisation on Aboriginal people in Victoria from the 1840s. Commissioned by James Dawson in 1885, a white settler and outspoken champion of Aboriginal interests, this monument has no parallel in Victoria. The obelisk’s height, prominent location and unusual inscriptions make a powerful public statement about the dispossession of Aboriginal people. The imposing monument stands in contrast with Dawson’s own modest family grave which commemorates himself and his daughter Isabella, amongst others. Together James and Isabella worked with the local Aboriginal people to record their languages and culture, drawing on the knowledge of elders including Wombeetch Puyuun, with whom Dawson formed a particularly strong friendship

(Criterion A)

The Wombeetch Puyuun Grave Monument and Dawson Family Grave is rare in Victoria. There are few large-scale colonial monuments commemorating an Aboriginal person or group in Victoria dating from the nineteenth century. The obelisk is of a conventional European design but has highly unusual features including the inscription of Aboriginal cultural symbols (a liangle, a boomerang and a message stick) and the dates ‘1840’ and ‘1883’ representing James Dawson’s view that the local Aboriginal people were dispossessed during this time. The inscription of Wombeetch Puyuun’s name in his own language is uncommon for the era, and so is his burial in a Christian section of the cemetery after exhumation from the ‘Aboriginal section’ of the segregated cemetery.

(Criterion B)

The Wombeetch Puyuun Grave Monument and Dawson Family Grave are of social significance to Eastern Maar people including the descendants of the Liwura Gundidj clan of the Djargurd Wurrung people. The monument is well-known and visited by the Eastern Maar and other Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Victorians (and Australians) interested in the colonial history of Victoria and reconciliation. The story of the Wombeetch Puyuun and James Dawson has found an audience beyond Camperdown and Western Victoria and resonates across the State. It speaks to the impact of European colonisation on Aboriginal communities from the early 1800s to today, which is an important and challenging history that contributes to Victoria’s contemporary sense of identity.

(Criterion G)

The Wombeetch Puyuun Grave Monument and Dawson Family Grave is historically significant for its association with Wombeetch Puyuun, James Dawson and his daughter, Isabella. Together the monument and grave speak to the close friendship of Wombeetch Puyuun and James Dawson, Dawson’s grief at the loss of Wombeetch Puyuun in 1883, and his despair at the colonial devastation of the local Aboriginal people. Wombeetch Puyuun was an elder in his own community and holder of knowledge. Through his friendship with James and Isabella Dawson he was instrumental as a teacher enabling the Dawsons to record language and customs which survive in the book Australian Aborigines: the languages and customs of several tribes in the Western District of Victoria (1881). This work remains an important source for Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people in Australia. It is notable that James Dawson gave up the grave plot originally purchased for his own family, in order to erect the Wombeetch Puyuun Grave Monument, he and his own family being buried in modest graves.

(Criterion H)

Show more

Show less

-

-

WOMBEETCH PUYUUN GRAVE MONUMENT & DAWSON FAMILY GRAVE - History

The Djargurd Wurrung people

The Djargurd Wurrung people are the traditional owners of the Camperdown area and lived on the land for countless generations before European colonisation. In the 1830s, the first British settlers arrived in the area and established sheep and cattle runs on this land. As the number of Europeans increased in the 1840s, Aboriginal peoples’ lives were devastated by the loss of hunting grasslands, lack of access to water, introduced diseases and violence. In 1839, between 35 and 40 Djargurd Wurrung people - including men, women and children - were massacred at a site that came to be known as Murdering Gully located on Mt Emu Creek near Camperdown. By 1861 there were twenty Djargurd Wurrung people residing in Camperdown and in 1865 most were forcibly moved to the Framlingham Aboriginal Station near Warrnambool. However, four elders refused to leave and stayed in Camperdown, including Wombeetch Puyuun.

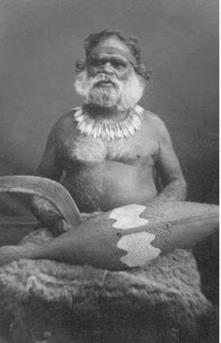

Wombeetch Puyuun

Wombeetch Puyuun was well-known around Camperdown and a member of the Liwura Gundidj clan of the Djargurd Wurrung. His year of birth cannot be confirmed, but there is some evidence that it was 1818 or earlier.[1] He was a leader, poet, astronomer and revered elder who held much cultural knowledge. Wombeetch Puyuun was known by white settlers as ‘Camperdown George’ (at this time it was common for Aboriginal people to be given and/or take on a European name). He was widely liked and reported to possess a ‘kindly nature’.[2] Wombeetch Puyuun had a close friendship with James Dawson. Through this relationship, he contributed to Dawson’s and Isabella Dawson’s (James’ daughter) understanding of the language and culture of the local Aboriginal people. Wombeetch Puyuun died on 26 February 1883. He was buried initially on an area of land on the periphery of the Camperdown Cemetery that was set aside for the burial of Aboriginal people.[3]

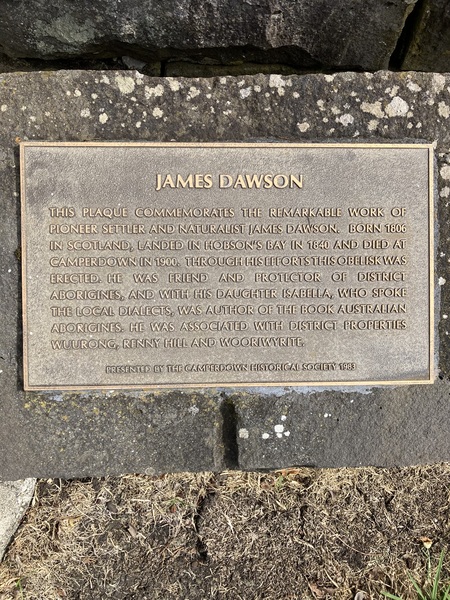

James and Isabella Dawson

James ‘Jimmy’ Dawson (1806-1900) was a figure of importance in Victoria’s history: he was a rare colonial voice advocating justice for Aboriginal people. A Scottish pastoralist and businessman, he lived in the Camperdown district from 1868 until his death in 1900. He formed close relationships with the local Aboriginal people, most notably Wombeetch Puyuun, which has been attributed to an outlook shaped by his staunch Presbyterianism. Together with his only child, daughter Isabella, Dawson diligently recorded Aboriginal languages and culture, and Wombeetch Puyuun was a key informant.[4] In 1876 Dawson was appointed a ‘Local Guardian of Aborigines’ (a term used in the Aboriginal Protection Act 1869) and in 1881 he published Australian Aborigines: the languages and customs of several tribes in the Western District of Victoria. This work remains an important source of information about Aboriginal languages and culture in Victoria today. It is thought that Isabella, a gifted linguist, researched and wrote much of the content of this book.

Dawson publicly advocated for Aboriginal people and highlighted injustice at a time when such activism was rare. A prolific letter writer to the press, he shone a light on the effects of colonial dispossession of Aboriginal people. He gave evidence to the 1877 Royal Commission on Aboriginal people criticising the assumptions behind government policy, stating that the Aboriginal people should be entitled to government support without obligation, and that it was unfair to restrict their movement and impose employment and religion.[5] Dawson continued writing letters to the press advocating to improve the rights and conditions of Aboriginal people into his 90s. A man with a ‘great force of character’, Dawson’s support of Aboriginal people made him an unpopular figure in some white colonial circles in the Western District and in Melbourne.[6]Wombeetch Puyuun Grave MonumentThe death of Wombeetch Puyuun in 1883 occurred while Dawson was in Scotland. On his return in 1884, Dawson was horrified to discover that his friend was buried in the ‘Aboriginal section’ of Camperdown cemetery with no headstone.[7] During the nineteenth century, it was common for Aboriginal people (when interred by white people) to be buried in a segregated ‘Aboriginal section’ on the periphery of town cemeteries. Grieving for his friend and indignant at this disrespect, Dawson set about commemorating Wombeetch Puyuun (who was a Christian) in a more dignified fashion. He commissioned a monumental obelisk costing over £185 (an extraordinary amount of money at the time). Dawson published a letter in the Camperdown Chronicle asking for public subscriptions.[8] He received little assistance, with locals writing to him ‘I have always looked on the blacks as a nuisance, and hope the trustees will forbid its erection’ and ‘I cannot see the use of it’.[9]

In mid-1885, Dawson supervised the erection of the Wombeetch Puyuun Grave Monument in a prominent position within the cemetery on acentral open area. Dawson then received permission from the Attorney-General to exhume and reinter the body of Wombeetch Puyuun at the foot of the obelisk, which he did with his own hands.[10] The events surrounding Dawson’s construction of the monument are described in many contemporary sources as far away as Sydney, such was the rarity of Dawson’s actions:

On visiting the cemetery, and outside the block of ground assigned to the interment of white people, a boggy, scrubby spot was pointed out to him [James Dawson] as the burying ground of the aborigines, and a hole, wherein the hind legs of a horse got bogged, as the grave of Wombeetch Puyuun, alias 'Camperdown George’… He was so shocked on seeing the spot in which the last of the original owners of that fine country had been buried like a dog by a so-called Christian community that he determined to take steps to remove, if possible, a blot from the occupiers of the country of which the aboriginals had been dispossessed, by raising an obelisk to their memory.[11]Dawson’s monument was the grandest of several colonial monuments/headstones in Victoria to the ‘last’ Aboriginal chief/person/tribe of an area.[12] This tradition was based on the mistaken belief that once the ‘original tribal people’ had passed away, Aboriginal communities and culture would become ‘extinct’. The dates 1840 and 1883 inscribed on the obelisk are not Wombeetch Puyuun’s birth dates. They represent Dawson’s view that the colonial devastation of the Djargurd Wurrung people began in 1840 and culminated in 1883 when Wombeetch Puyuun died. Specific dates marking the ‘start’ and ‘end’ of a colonial conflict are rare on monuments to Aboriginal people: they are reminiscent of the dates on a war memorial. In the context of the forced relocation of Aboriginal people to Framlingham Aboriginal Station, Dawson understood Wombeetch Puyuun as the ‘last’ member of the Liwura Gundidj Clan to live on his country. This does not mean, however, that Wombeetch Puyuun was the ‘last’ member of the Liwura Gundidj Clan, as the inscription suggests, nor that Aboriginal people from other parts of Victoria ever lived on their country. The descendants of the Djargurd Wurrung and Liwura Gundidj survive and thrive to this day in Western Victoria and beyond.

The Wombeetch Puyuun Grave Monument was the tallest monument in the Camperdown Cemetery for many decades. It was built in front of a tree on a gentle slope and provides a view over the landscape to the east. It appears to be the largest and grandest colonial monument in Victoria to an Aboriginal person or group (see Comparisons section). Dawson’s exhumation of Wombeetch Puyuun’s body and reinterment in a place of greater dignity was an extraordinary act for its time. The obelisk acknowledges the destruction caused by white settlers, something which Dawson wrote explicitly about and viewed as immoral. The monument can be read as the work of a white settler coming to terms with his relationship to the dispossession of Aboriginal people. In many respects Dawson was a man ahead of his time and advocated strongly for the rights of Aboriginal people and the improvement of their living conditions, which set him apart from his contemporaries. Dawson’s motivations to erect the Wombeetch Puyuun Grave Monument were likely complex: infused with his Presbyterian beliefs and understandings of race in the British world at that time. The monument and related documentary evidence speak to Dawson’s grief at the loss of his friend Wombeetch Puyuun, anger at the treatment of Aboriginal people by Europeans, as well as a desire for redemption as a white settler.

The tree

The tree behind the monument is a Brachychiton populneus subsp. populneus (Kurrajong). This is an unusual choice of planting for Southwest Victoria. The species is not indigenous to the region but a native of Northeast Victoria and Gippsland. It is unclear when the current tree was planted, but it is likely that it dates from the early twentieth century or earlier. The 1968 State Library of Victoria photo also depicts a Kurrajong.The Dawson Family Grave

The Dawson Family Grave is located in the Presbyterian Section No.2 of the Camperdown Cemetery. The two headstones are ‘In Memory of’ five family members, including James Dawson and his daughter Isabella. Although commemorated on a headstone at the Dawson Family Grave, information provided by the Camperdown Cemetery Trust suggests that James Dawson may have actually been interred in an unmarked grave near to the Family Grave on 21 April 1900 (Presbyterian area, Section 2, Grave No.1).[13] This requires further research and confirmation. At the present time, the Dawson Family Grave publicly commemorates James and Isabella Dawson. The Wombeetch Puyuun Grave Monument and the Dawson Family Grave together speak to the relationship of respect between James and Wombeetch Puyuun, and the actions of James and Isabella to advocate for Aboriginal people. Today, the Eastern Maar people hold James and Isabella Dawson in high esteem for their efforts to defend the rights of their people at a time when such acts of what some may now see as ‘reconciliation’ were uncommon.Significance to descendants

All graves and burial sites are significant as places of mourning and remembrance for family members and descendants. The Wombeetch Puyuun Grave Monument and Dawson Family Grave are significant at a family level to:

- Descendants of Wombeetch Puyuun’s family

- Descendants of James and Isabella Dawson, and other family members interred in the family plot.

Significance to the Eastern Maar People

This place is of social significance to the Eastern Maar people, including the descendants of the Liwura Gundidj clan of the Djargurd Wurrung people. There is a strong and special attachment between the Eastern Maar people and the Wombeetch Puyuun Grave Monument as well as the Dawson Family Grave. The Wombeetch Puyuun Grave Monument is well known and often visited by the Eastern Maar people and taught about in Western District schools. There is an understanding within that community of the importance of the relationship between Wombeetch Puyuun and James Dawson, and the role of James and Isabella Dawson collecting and recording the Aboriginal languages and cultures of the area in the late nineteenth century.

There is evidence of a time depth to that attachment from the 1880s to today. In April 2022 John Clarke of the Eastern Maar Aboriginal Corporation attested to this strong and special association with the place [14]. He noted that:

- The Eastern Maar view both the Wombeetch Puyuun Grave Monument and the Dawson Family Grave as significant because together both graves are ‘reconciliation in reality’.

- The Aboriginal community would like to ‘honour the Dawsons for their work’. In its own time James Dawson was ostracised from white social circles because he ‘pointed the finger at the atrocities’.

- James and Isabella Dawson are highly regarded by the Eastern Maar. Their work to record Aboriginal languages and customs of the district has contributed to ‘ensuring the survival’ of the Eastern Maar.

The story of the Wombeetch Puyuun and James Dawson has also found an audience beyond the Eastern Maar, Camperdown and Western Victoria and resonates across the State. The monument is unusual in Australia and well-known and visited by other Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Victorians (and Australians) interested in the colonial history, frontier relationships between settler and First Nations people, and reconciliation. The monument has been written about extensively for a general audience on the Internet and in books, as well as analysed in academic articles. It speaks to the impact of European colonisation on Aboriginal communities from the early 1800s to today, which is an important and challenging history that contributes to Victoria’s contemporary sense of identity.

It should also be noted that the Wombeetch Puyuun Grave Monument is included in the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Register (VAHR).

The ‘Aboriginal section’ of the Camperdown Cemetery (Wombeetch Puyuun’s original burial place) is also of significance to the Eastern Maar people. This land was sold many years ago to a private landowner and no headstones or monuments are visible on it. The Eastern Maar people are knowledge-holders about this place.

[1] 'News and Notes', Camperdown Chronicle, Wed 28 Feb 1883, p. 2; Jan Critchett, Untold Stories: Memories and Lives of Victorian Kooris, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne 1998, p.220.

[2] 'News and Notes', Camperdown Chronicle; Jan Critchett, Untold Stories.

[3] Jan Critchett, Untold Stories, p.225-26.

[4] Context, Camperdown Botanic Gardens and Arboretum Conservation Management Plan, 18 April 2017.

[5] Peter Corris, Dawson, James (Jimmy) (1806–1900), Australian Dictionary of Biography, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/dawson-james-jimmy-3381 [Accessed 29 April 2022]

[6] ‘The Passing of the Pioneers: Death of Mr. James Dawson’, Camperdown Chronicle, 21 April 1900.

[7] See Jan Critchett, Untold Stories: Memories and Lives of Victorian Kooris, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne 1998, p.225-26. The land at Camperdown Cemetery once set aside for Aboriginal burials was subsequently sold to a private individual and is no longer on public land.

[8] ‘In Memoriam of the Aborigines’, Camperdown Chronicle, Sat 20 Dec 1884, p.3

[9] 'Last of the Tribe', Australian Town and Country Journal, Sat 7 Aug 1886, p.19.

[10]See ‘Memorial Obelisk to the Aborigines’ Australasian Sketcher with Pen and Pencil, 7 Apr 1886; 'Delving into the Past, Camperdown Chronicle, 18 Jan 1938.

[11] ‘Memorial to the Aborigines’, Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, Sat 12 Dec 1885, p. 1233.

[12] See David Hansen, ‘Headstone’, Griffith Review, https://www.griffithreview.com/articles/headstone/ [Accessed 7 June 2022].

[13] Discussion with the Camperdown Cemetery Trust, April 2022 & July 2022.

[14] John Clarke, General Manager, Bio-cultural Landscapes at Eastern Maar Aboriginal Corporation, onsite interview, 11 April 2022.

Selected bibliography

Jan Critchett, Untold Stories: Memories and Lives of Victorian Kooris, MUP, Melbourne 1998.

Context, Camperdown Botanic Gardens and Arboretum Conservation Management Plan, 18 April 2017.

Corris, Peter Dawson, James (Jimmy) (1806–1900), Australian Dictionary of Biography, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/dawson-james-jimmy-3381 [Accessed 29 April 2022]

Raymond Madden, ‘James Dawson's Scrapbook: advocacy and antipathy in colonial Western Victoria’, La Trobe Journal, No.85, May 2010.

'Delving into the Past, Camperdown Chronicle, Tue 18 Jan 1938, p. 4.

‘In Memoriam of the Aborigines’, Camperdown Chronicle, Sat 20 Dec 1884, p.3

'Last of the Tribe', Australian Town and Country Journal, Sat 7 Aug 1886, p.19.

‘Man's fight for his country is rewarded, 130 years on’, Standard, 7 November 2012.

‘Memorial Obelisk to the Aborigines’ Australasian Sketcher with Pen and Pencil, Wed 7 Apr 1886.

'News and Notes', Camperdown Chronicle, Wed 28 Feb 1883.

‘The Passing of the Pioneers: Death of Mr. James Dawson’, Camperdown Chronicle, 21 April 1900.

Interviews

The Executive Director thanks the following people for contributing their knowledge and information to the assessment process:- John Clarke, General Manager, Bio-cultural Landscapes at Eastern Maar Aboriginal Corporation & Nathalia Guimares, Cultural Heritage Manager, Eastern Maar Aboriginal -Corporation (Onsite interview, 11 April 2022)- Colin Hayman and Sylvia Walton, Camperdown Cemetery Trust (Onsite interview, 11 April 2022, Further correspondence 19 July 2022)- Descendants of James Dawson: Nick Cole, Tim Thornton and Tom Thornton (Interview in Camperdown, 11 April 2022)- Bob Lambell, Vice-President, Camperdown and District Historical Society, 13 July 2022.WOMBEETCH PUYUUN GRAVE MONUMENT & DAWSON FAMILY GRAVE - Assessment Against Criteria

Criterion

The Wombeetch Puyuun Grave Monument and Dawson Family Grave is of historical significance to the State of Victoria. It satisfies the following criteria for inclusion in the Victorian Heritage Register:

Criterion A

Importance to the course, or pattern, of Victoria's cultural history.

Criterion B

Possession of uncommon, rare or endangered aspects of Victoria’s cultural history.

Criterion G

Strong or special association with a particular present-day community or cultural group for social, cultural or spiritual reasons.

Criterion H

Special association with the life or works of a person, or group of persons, of importance in Victoria’s history.

WOMBEETCH PUYUUN GRAVE MONUMENT & DAWSON FAMILY GRAVE - Permit Exemptions

General Exemptions:General exemptions apply to all places and objects included in the Victorian Heritage Register (VHR). General exemptions have been designed to allow everyday activities, maintenance and changes to your property, which don’t harm its cultural heritage significance, to proceed without the need to obtain approvals under the Heritage Act 2017.Places of worship: In some circumstances, you can alter a place of worship to accommodate religious practices without a permit, but you must notify the Executive Director of Heritage Victoria before you start the works or activities at least 20 business days before the works or activities are to commence.Subdivision/consolidation: Permit exemptions exist for some subdivisions and consolidations. If the subdivision or consolidation is in accordance with a planning permit granted under Part 4 of the Planning and Environment Act 1987 and the application for the planning permit was referred to the Executive Director of Heritage Victoria as a determining referral authority, a permit is not required.Specific exemptions may also apply to your registered place or object. If applicable, these are listed below. Specific exemptions are tailored to the conservation and management needs of an individual registered place or object and set out works and activities that are exempt from the requirements of a permit. Specific exemptions prevail if they conflict with general exemptions. Find out more about heritage permit exemptions here.WOMBEETCH PUYUUN GRAVE MONUMENT & DAWSON FAMILY GRAVE - Permit Exemption Policy

The following permit exemptions are not considered to cause harm to the cultural heritage significance of the Wombeetch Puyuun Grave Monument and Dawson Family Grave.

General- Minor repairs and maintenance which replaces like with like. Repairs and maintenance must maximise protection and retention of fabric and include the conservation of existing details or elements. Any repairs and maintenance must not exacerbate the decay of fabric due to chemical incompatibility of new materials, obscure fabric or limit access to such fabric for future maintenance.

- Works or activities, including emergency stabilisation, necessary to secure safety in an emergency where a structure or part of a structure has been irreparably damaged or destabilised and poses a safety risk to its users or the public. The Executive Director must be notified within seven days of the commencement of these works or activities.

- Gentle cleaning including the removal of surface deposits by the use of low-pressure water (to maximum of 300 psi at the surface being cleaned) and neutral detergents (not household bleach) and mild brushing and scrubbing with plastic – not wire – brushes.

Gardening, trees and plants- The processes of gardening including mowing, pruning, mulching, fertilising, removal of dead or diseased plants, disease and weed control and maintenance to care for existing plants.

- Removal of tree seedlings and suckers without the use of herbicides.

- Management and maintenance of trees including formative and remedial pruning, removal of deadwood and pest and disease control.

- Emergency tree works to maintain public safety provided the Executive Director, Heritage Victoria is notified within seven days of the removal or works occurring.

- Removal of noxious weeds.

Hard Landscape Elements- Removal of the early 2000s seat.

Cemetery-related works (to graves other than that of Wombeetch Puyuun and the Dawson Family)- Interments, burials and erection of monuments, re-use of graves, burial of cremated remains, and exhumation of remains.

-

-

-

-

-

Tilia x europaea

National Trust

National Trust -

Elaeodendron croceum

National Trust

National Trust -

Quercus lanata

National Trust

National Trust

-

'Lawn House' (Former)

Hobsons Bay City

Hobsons Bay City -

1 Fairchild Street

Yarra City

Yarra City -

10 Richardson Street

Yarra City

Yarra City

-

-