JANET CLARKE HALL

57-63 COLLEGE CRESCENT PARKVILLE, MELBOURNE CITY

-

Add to tour

You must log in to do that.

-

Share

-

Shortlist place

You must log in to do that.

- Download report

Statement of Significance

What is significant?

How is it significant?

Why is it significant?

Janet Clarke Hall is also significant for the following reasons, but not at the State level:

-

-

JANET CLARKE HALL - History

HISTORY

Contextual history

[Information largely from Lovell Chen, 'Janet Clarke Hall, The University of Melbourne, Royal Parade, Parkville', prepared for Gray Puksand, December 2006, Revised April 2007.]

The University of Melbourne was founded in 1853 and an open site of 25 acres (10 hectares, later increased to 100 acres or 40 hectares) north of the city was chosen. The university developed on the southern part of the site and the colleges and the university oval on the northern part. In 1861 a plan was approved to subdivide the northern section into four equal areas of 10 acres each allocated to the Church of England, the Presbyterian, the Wesleyan Methodist and the Roman Catholic churches. The land backing onto the college sites became the recreation oval, for use by the colleges and university.

For its first quarter century the university taught only men, but an 1880 amendment to the University Act allowed the first women to enrol in the Faculty of Arts in 1881. Women were admitted to first year medical lectures in 1887 and into the Law School in 1889.

The first of the university residential colleges to be built was Trinity College, established under the aegis of the Church of England and its first Bishop of Melbourne, Bishop Perry. The architect Leonard Terry developed a master plan in 1869 and the first building opened in 1872. The College was founded to train theological students, to house graduates and provided a supervised residence and tuition to undergraduates from country areas. The classics scholar Alexander Leeper was appointed as the first Warden and Principal.

Women were admitted to Trinity College as non-residents members from 1883. Leeper in 1884 visited educational institutions overseas, and became convinced of the need to establish a residential women's college. The first accommodation for female students at Trinity College was provided in 1886 in a rented house in Sydney Road, with residents able to attend tutorials and communion at Trinity, but their social contact with male students was severely restricted.

Alexander Leeper (1848-1934)

[From Australian Dictionary of Biography, online edition at http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/leeper-alexander-7154, accessed 27 November 2013.]

Alexander Leeper has been described as the founder of the collegiate system in the University of Melbourne. Born in Dublin, he was a brilliant student, and won prizes and exhibitions at Trinity College, Dublin and St John's College, Oxford. Leeper first visited Australia in 1871, and in 1874 he returned from Oxford to Sydney before accepting an appointment at Melbourne Church of England Grammar School. In 1876 Leeper was appointed principal of Trinity College, and was determined to develop a new Australian form of collegiate life. But Trinity's financial base remained precarious, and the continuance of the collegiate system was only ensured with the opening of Ormond College in 1881 and of Queen's College in 1888. The three colleges came to dominate the university academically and in large degree politically.

From 1899 and 1900 he was a council member of Melbourne Grammar and of Melbourne Church of England Girls' Grammar School. He was active in the Classical Association of Victoria, organized the Shakespeare Society and had an interest in modern literature. He was active in Church affairs, in Trinity's theological school and was a lay canon of St Paul's Cathedral and a member of Synod.

Leeper retired from Trinity in 1918, and his principal interest in retirement were the Public Library, Museums and National Gallery, of which he was a trustee in 1887-1928, becoming president in 1920, and was on the Felton Bequests' Committee (1920-28).

Janet Lady Clarke (1851-1909)

[From Australian Dictionary of Biography, online edition at http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/clarke-janet-marion-3224, accessed 27 November 2013.]

Janet Clarke was the eldest daughter of the pastoralist Peter Snodgrass. She became governess to William Clarke's children late in the 1860s and married him in 1873. Janet was the inspiration behind the lavish hospitality for which the Clarkes became famous in the 1880s and 1890s, at both their country property Rupertswood and their town house, Cliveden. Janet led society in Victoria for thirty years and was one of Australia's best-known women.

Like her husband Sir William, Janet felt that wealth brought her obligations to people and organizations in need, and she was a vigorous supporter of philanthropic, cultural, educational and political movements. Her contributions to education included helping to establish the College of Domestic Economy, acting on the committee to extend Church of England schools for girls, and serving on the council of the Melbourne Church of England Grammar School for Girls. Her most notable donation was £5000 to the building of the Trinity College Hostel, later called Janet Clarke Hall. In 1904 she was president of the University Funds Appeal which raised £12,000.

After her husband died in 1897, Janet lived at Cliveden until she died in 1909. The rotunda in the Alexandra Gardens, Melbourne, was built in her memory.

Place history

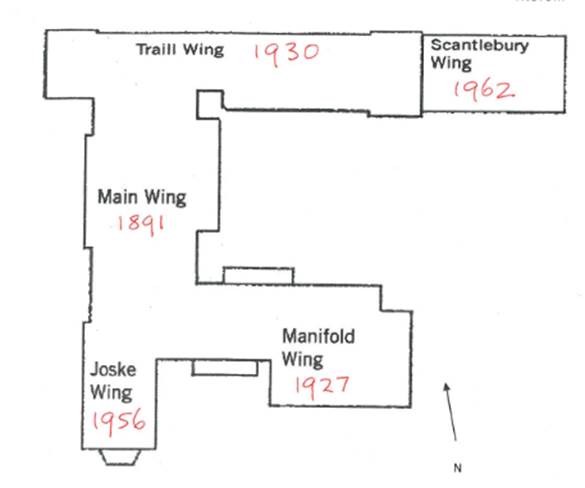

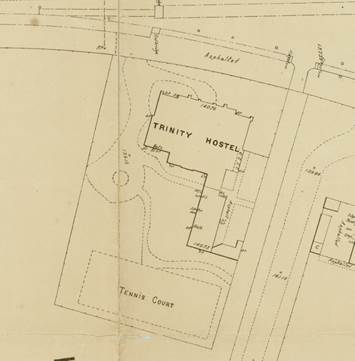

In 1888 the Warden of Trinity College, Dr Alexander Leeper, submitted a proposal for the establishment of a women's hostel on land in the north-west corner of the Trinity grounds. Janet Lady Clarke, the wife of Sir William Clarke, donated £5000 towards the building fund and a further £2000 was donated by Sir Matthew Henry Davies. In 1889 selected architects were invited to submit designs for the new building, which was to be of red brick with dressings of Waurn Ponds stone, and contain a bedroom, sitting room and office for the Principal, a dining room, a general reception room, as well as students' rooms. The design of the architect Charles D'Ebro was chosen, a tender of £5,413 was accepted from builder Thos Corley (though it was to cost £7,546 to build and furnish). The foundation stone was laid by the Governor Lord Hopetoun on 17 March 1890 and the new college, called the Trinity College Hostel, was opened by him on 15 April 1891. It was the first female residential college in Australia. It housed at first only six women students.

The Trinity College Council authorised a committee of twelve ladies, including Janet Lady Clarke, Lady Davies and Mrs Leeper to assist in the management and select the new Principal, Emily Hensley, who came from England to take up the position.

In 1921 the Hostel was renamed Janet Clarke Hall, to acknowledge the role played by the late Janet Clarke in its establishment.

Manifold Wing

A bequest from the pastoralist William Thompson Manifold allowed for the construction of a new brick wing, called the Manifold Wing, designed by the architects Blackett & Foster and built by Thompson & Chalmers, which opened on 17 October 1927. This was built to the east of the southern side of the main building, and included a dining hall and kitchen on the ground floor, students' room on the first and second floors above and bathrooms. These works, together with alterations to the main building cost £23,000, of which £14,500 was from the Manifold bequest.

Traill Wing

Student numbers continued to increase in the 1920s, and in 1930 a donation of £5,000 from Elsie Traill, a former student and Chairman of the Hostel Committee, together with £7,000 advanced from the Trinity Building Fund, enabled the addition of the Traill Wing. It was designed by A & K Henderson, and built at the northern end of the main building. This provided a suite of rooms for the principal, Edith Joske, students' bed-sitting rooms, bathrooms, kitchenettes, laundries and a tutorial room, and allowed the College to accommodate all of its fifty students in the one building (some had until then been housed in an annexe across the road).

Enid Joske Wing

In 1954 the State Government granted an interest-free loan of £6,000 towards the construction of a new wing. Legacies from the late Dr Constance Ellis and Ethel Blaze contributed to the £19,866 required, and it was named after Enid Joske, a former resident who was principal for twenty-five years, from 1928-52. In 1956 the new wing, designed by the architect W Forsyth, was completed, linking the Manifold Wing with the 1891 building.

Joske strengthened the case for independence form Trinity College by fostering and consolidating a self-confident institution. In the 1950s financial assistance to university residential colleges from the Commonwealth Government allowed for the independence of Janet Clarke Hall from Trinity College, which was granted in 1961.

Lilian Scantlebury Wing

In 1962 the Traill Wing was extended eastwards, to designs by the architects Forsyth & Richardson, and was named after the Janet Clarke Hall Committee Chairman Lilian Scantlebury. This increased the capacity of the College to 106 students and was the last major addition to the College.

Later alterations

In 1973 male residential students were accepted into Janet Clarke Hall. Maintenance and upgrades occurred throughout the rest of the twentieth century. In the 1960s works included the repainting of the interiors, the replacement of old wooden doors with glass doors, the bathrooms were modernised and the first male toilet was installed. In the 1970s a new common room facing east into the courtyard was added, heating was introduced in the common areas and a new brick fence was constructed on Royal Parade. The gardens were also re-landscaped following the loss of some garden areas during building works.

Over the years the College has accommodated many students who have gone on to outstanding public careers including Australia's first (and so far the only) female Nobel Laureate Prof Elizabeth Blackburn, President oftheAustralian Human Rights Commission Prof Gillian Triggs, Chancellor of Sydney University Dame Leonie Kramer, Chancellor of Melbourne University Dr Fay Marles, Chancellor of La Trobe University Prof Adrienne Clarke and Vice-Chancellor of Deakin University Prof Sally Walker.

KEY REFERENCES USED TO PREPARE ASSESSMENT

Lovell Chen, 'Janet Clarke Hall, The University of Melbourne, Royal Parade, Parkville', prepared for Gray Puksand, December 2006, Revised April 2007.

Philip Goad & George Tibbits, Architecture on Campus. A Guide to the University of Melbourne and its Colleges, Carlton 2003.

JANET CLARKE HALL - Permit Exemptions

General Exemptions:General exemptions apply to all places and objects included in the Victorian Heritage Register (VHR). General exemptions have been designed to allow everyday activities, maintenance and changes to your property, which don’t harm its cultural heritage significance, to proceed without the need to obtain approvals under the Heritage Act 2017.Places of worship: In some circumstances, you can alter a place of worship to accommodate religious practices without a permit, but you must notify the Executive Director of Heritage Victoria before you start the works or activities at least 20 business days before the works or activities are to commence.Subdivision/consolidation: Permit exemptions exist for some subdivisions and consolidations. If the subdivision or consolidation is in accordance with a planning permit granted under Part 4 of the Planning and Environment Act 1987 and the application for the planning permit was referred to the Executive Director of Heritage Victoria as a determining referral authority, a permit is not required.Specific exemptions may also apply to your registered place or object. If applicable, these are listed below. Specific exemptions are tailored to the conservation and management needs of an individual registered place or object and set out works and activities that are exempt from the requirements of a permit. Specific exemptions prevail if they conflict with general exemptions. Find out more about heritage permit exemptions here.Specific Exemptions:PERMIT EXEMPTIONS (under section 42 of the Heritage Act)

It should be noted that Permit Exemptions can be granted at the time of registration (under s.42(4) of the Heritage Act). Permit Exemptions can also be applied for and granted after registration (under s.66 of the Heritage Act)

General Condition: 1.

All exempted alterations are to be planned and carried out in a manner which prevents damage to the fabric of the registered place or object.General Condition: 2.

Should it become apparent during further inspection or the carrying out of works that original or previously hidden or inaccessible details of the place or object are revealed which relate to the significance of the place or object, then the exemption covering such works shall cease and Heritage Victoria shall be notified as soon as possible.General Condition: 3.

All works should be informed by Conservation Management Plans prepared for the place. The Executive Director is not bound by any Conservation Management Plan, and permits still must be obtained for works suggested in any Conservation Management Plan.General Conditions: 4.

Nothing in this determination prevents the Executive Director from amending or rescinding all or any of the permit exemptions.General Condition: 5.

Nothing in this determination exempts owners or their agents from the responsibility to seek relevant planning or building permits from the relevant responsible authority, where applicable.Specific exemptions:

Exterior

. Minor repairs and maintenance which replace like with like.

. Removal of non-original items such as air conditioners, pipe work, ducting, wiring, antennae, aerials etc, and making good.

. Installation or removal of non-original external fixtures and fittings such as hot water services and taps.

. Installation and repairing of damp proofing by either injection method or grouted pocket method.

. Demolition of the shed at the rear of the Scantlebury Wing.

. Resurfacing of the tennis court and replacement of fencing.

Interior

. Removal of non-original shower and toilet partitioning and non-structural walls in bathrooms.

. Painting of previously painted walls and ceilings provided that preparation or painting does not remove evidence of any original paint or other decorative scheme.

. Installation, removal or replacement of non-original carpets and/or flexible floor coverings.

. Installation, removal or replacement of non-original curtain tracks, rods and blinds.

. Installation, removal or replacement of hooks, nails and other devices for the hanging of mirrors, paintings and other wall mounted art or religious works or icons.

. Installation of honour boards and the like.

. Removal or installation of notice boards.

. Demolition or removal of non-original stud/partition walls, suspended ceilings or non-original wall linings (including plasterboard, laminate and Masonite), non-original glazed screens, non-original flush panel or part-glazed laminated doors, aluminium-framed windows, bathroom partitions and tiling, sanitary fixtures and fittings, kitchen wall tiling and equipment, lights, built-in cupboards, cubicle partitions, computer and office fitout and the like.

. Removal or replacement of non-original door and window furniture including, hinges, locks, knobsets and sash lifts.

. Removal of non-original glazing to internal timber-framed, double hung sash windows, and replacement with clear or plain opaque glass.

. Refurbishment of existing bathrooms, toilets and kitchens including removal, installation or replacement of sanitary fixtures and associated piping, mirrors, wall and floor coverings.

. Removal of tiling or concrete slabs in wet areas provided there is no damage to or alteration of original structure or fabric.

. Installation, removal or replacement of ducted, hydronic or concealed radiant type heating provided that the installation does not damage existing skirtings and architraves and that the central plant is concealed.

. Installation, removal or replacement of electrical wiring provided that all new wiring is fully concealed and any original light switches, pull cords, push buttons or power outlets are retained in-situ. Note: if wiring original to the place was carried in timber conduits then the conduits should remain in situ.

. Installation, removal or replacement of electric clocks, public address systems, detectors, alarms, emergency lights, exit signs, luminaires and the like on plaster surfaces.

. Installation, removal or replacement of bulk insulation in the roof space.

. Installation of plant within the roof space.

. Installation of new fire hydrant services including sprinklers, fire doors and elements affixed to plaster surfaces.

. Installation of new built-in cupboards providing no alteration to the structure is required.

Maintenance and security

. All works to maintain, secure and make safe buildings of no cultural heritage significance.

. General maintenance of buildings of primary and contributory heritage significance. Such maintenance includes the removal of broken glass, the temporary shuttering of windows and covering of holes as long as this work is reversible.

. Painting of previously painted structures provided that preparation or painting does not remove evidence of the original paint or other decorative scheme.

. Erecting, repairing and maintaining signage (directional signage, road signs, speed signs).

JANET CLARKE HALL - Permit Exemption Policy

Preamble

The purpose of the Permit Policy is to assist when considering or making decisions regarding works to a registered place. It is recommended that any proposed works be discussed with an officer of Heritage Victoria prior to making a permit application. Discussing proposed works will assist in answering questions the owner may have and aid any decisions regarding works to the place.

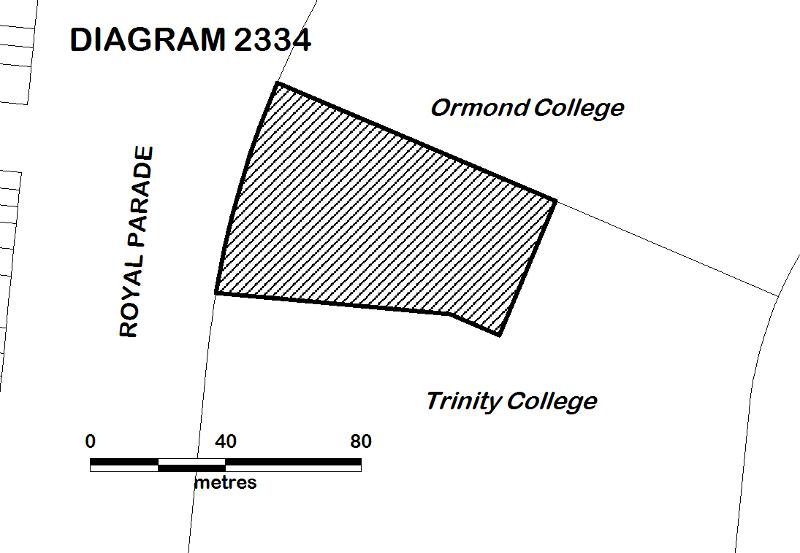

The extent of registration of Janet Clarke Hall on the Victorian Heritage Register affects the whole place shown on Diagram 2334 including the land, all buildings, roads, trees, landscape elements and other features. Under the Heritage Act 1995 a person must not remove or demolish, damage or despoil, develop or alter or excavate, relocate or disturb the position of any part of a registered place or object without approval. It is acknowledged, however, that alterations and other works may be required to keep places and objects in good repair and adapt them for use into the future.

If a person wishes to undertake works or activities in relation to a registered place or registered object, they must apply to the Executive Director, Heritage Victoria for a permit. The purpose of a permit is to enable appropriate change to a place and to effectively manage adverse impacts on the cultural heritage significance of a place as a consequence of change. If an owner is uncertain whether a heritage permit is required, it is recommended that Heritage Victoria be contacted.

Permits are required for anything which alters the place or object, unless a permit exemption is granted. Permit exemptions usually cover routine maintenance and upkeep issues faced by owners as well as minor works. They may include appropriate works that are specified in a conservation management plan. Permit exemptions can be granted at the time of registration (under s.42 of the Heritage Act) or after registration (under s.66 of the Heritage Act).

It should be noted that the addition of new buildings to the registered place, as well as alterations to the interior and exterior of existing buildings requires a permit, unless a specific permit exemption is granted.

Conservation management plans

Lovell Chen's 'Janet Clarke Hall, The University of Melbourne, Royal Parade, Parkville', Conservation Management Plan, dated December 2006 (Revised April 2007) may provide guidance for the future management of the place. It should be noted that all parts of the College building are included in the Registration and permits must be obtained for all works apart from those for which exemptions have been given.

Cultural heritage significance

Overview of significance

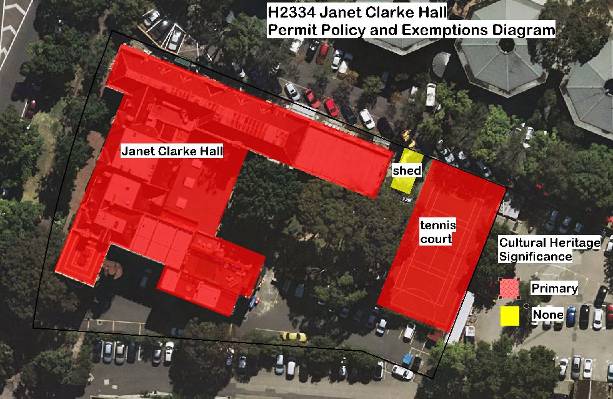

The cultural heritage significance of Janet Clarke Hall lies in its importance as the first residential college for women in Australia. The main wing is an outstanding example of the Gothic Revival style applied to an institutional building, and the later wings differ in style but are sympathetic in their use of materials, their scale and general form. The building clearly demonstrates the various periods of construction, both externally and internally, and all wings are considered to be of primary significance as a demonstration of the history of the College. The tennis court at the rear has been in its present location since the 1890s, and is of historical significance as an important early feature and a very early example of its kind in Victoria, though it is unlikely that any original fabric remains.

a) All of the buildings and features listed here are of primary cultural heritage significance in the context of the place. The buildings of cultural heritage significance are shown in red on the diagram. A permit is required for most works or alterations. See Permit Exemptions section for specific permit exempt activities:

. All of the building known as Janet Clarke Hall

. The tennis court

b) Buildings and features that are not listed in a) or c) or are listed here are deemed to have contributory cultural heritage significance to the place. A permit is required for most works or alterations. See Permit Exemptions section for specific permit exempt activities:

. The landscape

c) The following buildings and features are of no cultural heritage significance. These are shown in yellow on the diagram. Specific permit exemptions are provided for these items:

. The shed at the rear of the Scantlebury Wing

. The car parking areas.

d) Archaeological: This place is not known to have any archaeological potential.

-

-

-

-

-

SHOPS AND RESIDENCES

Victorian Heritage Register H0043

Victorian Heritage Register H0043 -

CARLTON COURT HOUSE

Victorian Heritage Register H1467

Victorian Heritage Register H1467 -

CAMBRIDGE TERRACE

Victorian Heritage Register H1606

Victorian Heritage Register H1606

-

"1890"

Yarra City

Yarra City -

'BRAESIDE'

Boroondara City

Boroondara City -

'ELAINE'

Boroondara City

Boroondara City

-

-